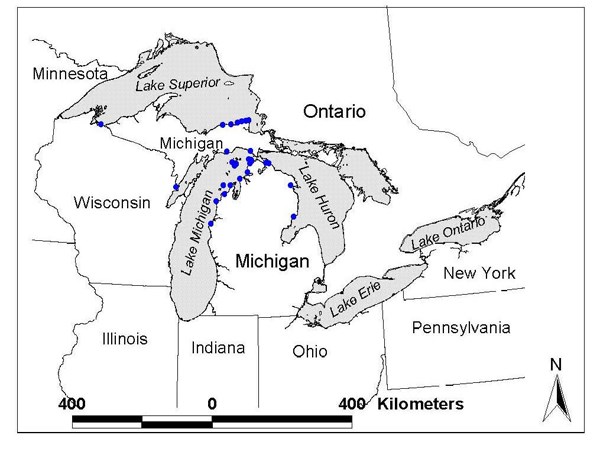

If you live within a birds flight of a national park, what you do in your backyard may affect how a pink lady slipper continues to thrive inside a park's boundaries. Everyone can be a park neighbor and here are some things we would like our neighbors to know. Dispose Fall Decorations By Marcus Key The last round of cold turkey leftovers officially marks the end of Thanksgiving. It's over. Time to start making the change from Fall to Winter. Put away the pumpkins, pull out the holly, untangle the lights, and replace all those woody bittersweet vines with evergreens. What should you do with that old wreath of bittersweet from the door, or those sprigs of brightly colored berries from the table? Trash them, don't compost them. More than likely the wreath and vine of bittersweet are oriental bittersweet, an invasive species, and its beautiful berries are spread around by birds in the winter. Oriental bittersweet vines climb high up on trees, the increased weight can lead to uprooting and blowing-over during high winds and heavy snowfall. In addition Oriental bittersweet is displacingnative American bittersweet through competition and hybridization. Staff and volunteers at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore cut and remove thousands of Oriental bittersweet vines from trees in the park every year. Disposing of the vines and berries in the trash prevents the invader from killing trees, and from being spread. Find out how to differentiate Oriental bittersweet from native American bittersweet. To learn about opportunities to remove bittersweet from Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore and other events visit our park calendar or our Facebook events page. Great Lakes Birds and Gulf Oil By Ted Gostomski, Network Science Writer Four people move slowly down the face of a dune toward the shoreline, their eyes focused on two light-colored specks just ahead that are moving slowly along the brightly glaring sand. When the two specks – an adult Piping Plover and its newly-hatched chick – spot the group, they do what comes naturally: they run for the water's edge. But when the group presses closer, the adult takes the next natural step and flies out over the water and down the shoreline to safety. The chick, however, is still to young to fly and so is trapped as the group forms a U around it, pinning the three-inch-high bird between themselves and the water. The chick skitters back and forth, looking for an opening. It sees a gap between someone's legs and tries to escape, but a hat dropped down in front of it gently scoops the small bird off the ground. Another young plover will be banded here today.

Alice Van Zoeren 2005

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service The news was looking up in late July and early August, as the leaking well was capped and the oil began to dissipate faster than expected. Gulf Islands National Seashore (Florida/Mississippi) reported successful nesting among colonial waterbirds despite some signs of contamination earlier in the season.4 additionally, it was reported that “south Florida, the Florida Keys, and the east coast of the Florida Peninsula are not likely to experience any effects from oil remaining on the surface of the gulf, as it continues to degrade and remains hundreds of miles away from the loop current.” Only time and good long-term monitoring data will tell if Great Lakes birds avoid the ill effects of the oil spill disaster. Whether it is the Network’s songbird monitoring or the Piping Plover monitoring conducted by the parks, the information we have collected gives us a baseline for comparing future data. Beyond the data, though, is the joy of actually seeing a young Piping Plover run along the beach, and we can only hope for that in the years to come. References

|

Last updated: January 18, 2018