Photo: copyright Michael Durham. OverviewHigh-elevation subalpine forests define the upper limit of tree growth in the Sierra Nevada. While these trees intermingle with other tree species at their lower edges, at their upper limits, known as treeline, they usually grow in single-species stands. They must withstand harsh growing conditions, including cold temperatures, severe winds, and a short growing season. The two high-elevation species we monitor are foxtail pine and whitebark pine. These trees are known as white pines or "five-needle" pines, as their needles grow in bundles of five. These pines play important roles where they grow, regulating processes such as snowmelt and stream flow and providing habitat and food for birds and mammals. All western species of five-needle white pines are threatened by an invasive pathogen that causes the disease white pine blister rust. The threats of blister rust and mountain pine beetle coupled with warming temperatures and projected changes in type and timing of precipitation heighten the importance of monitoring white pine forests. Information about the health of these forests and how they are changing helps park managers work with partners within the region to plan for and address anticipated declines in these iconic forests.

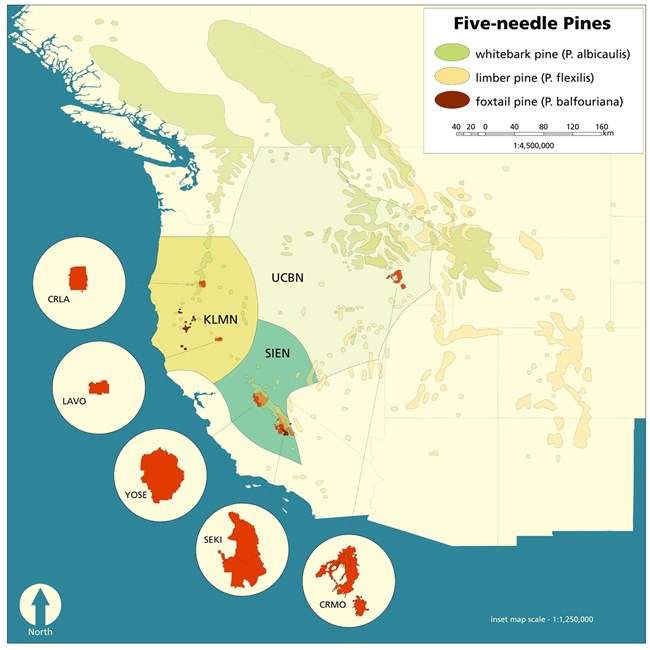

Photo: Peggy Moore Species MonitoredWhitebark PineWhitebark pine has a wide geographic range in the west, including in the Rocky Mountains, the Cascades, and the Sierra Nevada, where it reaches its southern limit near Mt. Whitney in Sequoia National Park. Whitebark pine occurs on both the west and the more arid east side of the Sierra crest in scattered treeline stands. The seeds of whitebark pine provide an important food source for many seed-eating birds and mammals. Whitebark pine is entirely dependent upon Clark’s Nutcracker (a medium-sized relative of the crow) for dispersal of its large wingless seeds. While severe declines in whitebark pine are occurring in most of its range, Sierra Nevada populations are still relatively healthy. However, in 2021, local scientists and park staff began observing whitebark pine dieback and mortality in Kings Canyon National Park. Since then, our forest monitoring crew started documenting additional areas of dieback and mortality of whitebark pine and foxtail pine in our network parks, often associated with bark beetles or occasionally with signs of white pine blister rust infection.

NPS / Sean Auclair Whitebark Pine Listed as ThreatenedOn December 15, 2022, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) listed whitebark pine as threatened with potential extinction under the Endangered Species Act. FWS determined that the primary stressor driving the status of whitebark pine is white pine blister rust, a fungal disease caused by the nonnative pathogen Cronartium ribicola. Whitebark pine is also negatively affected by the mountain pine beetle, altered fire regimes, and the effects of climate change.

NPS photo Foxtail PineIn contrast to whitebark pine, foxtail pine has a limited distribution. It is endemic to California and is confined to two discrete regions: the Klamath Mountains of northwestern California and the southern Sierra Nevada. Foxtail pine nearly always grows as an upright tree (very rarely as a shrubby krummholz form), even on the highest, most windswept and exposed sites. These trees are limited to high-elevation slopes, ridges and peaks, typically growing in open stands that are almost purely foxtail pine with little other vegetation. Like the whitebark pine, foxtail pine provide important habitat and food for birds and mammals. The oldest known foxtail is over 2,000 years old. Both live and dead wood of this species can be dated to produce multi-millennial tree-ring records used to reconstruct long-term variations in climate. Increasing Dieback and Mortality ObservedIn 2022, our forest monitoring crew began documenting branch dieback and mortality of foxtail pine in areas they traveled to our white pines monitoring plots. They photographed and documented signs of mountain pine beetles on some of these affected trees, as well as signs of white pine blister rust infection, noted particularly in the Chicken Spring Lake area just outside of Sequoia National Park.

Approach and ObjectivesThis monitoring project was developed collaboratively with the Upper Columbia Basin and Klamath Networks (see map to right). This collaboration will provide comparable data on blister rust infection rates and damage, pine beetle outbreaks, and tree mortality across a large region. Since the protocol was implemented, another network has implemented it: Mojave Desert Network began monitoring limber pine and Great Basin bristlecone pine in Great Basin National Park. Randomly located permanent plots in white pine stands are monitored on a three-year rotation to obtain tree-and plot-level data. For white pine forest communities in Klamath, Sierra Nevada, and Upper Columbia Basin Network parks, we quantify status and trends in:

Quick ReadsPublications and Other InformationSource: NPS DataStore Saved Search 990. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore. The following reports are associated with this monitoring project or with closely associated research projects. Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 1004. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore. These protocol documents provide detailed information about how this monitoring project is conducted. Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 1020. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Follow along as we study the subalpine forests of the Sierra Nevada, including whitebark pine and the rare and long-lived foxtail pine. |

Last updated: April 25, 2025