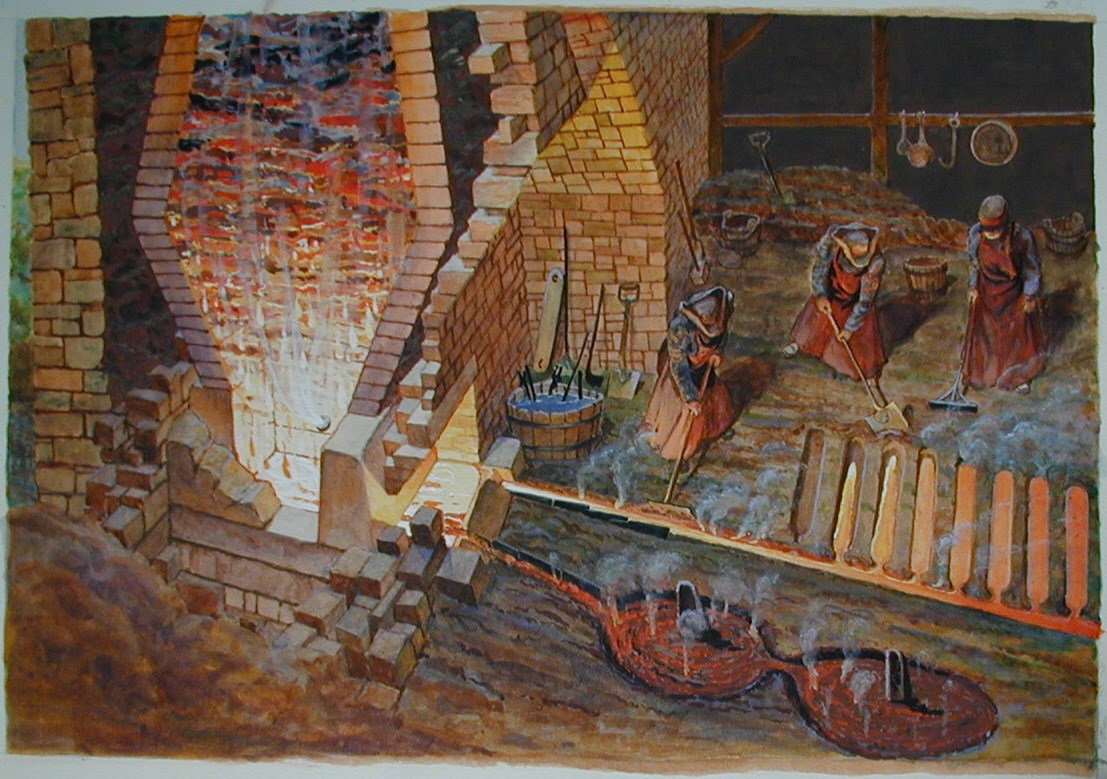

NPS Photo An ancient alchemy sustained Hopewell Furnace: transforming mineral into metal. Since 4,000 years ago, when humans learned how to free iron from ore, the basic process has not changed. Iron oxide is heated in an intense flame fed by carbon fuel. Oxygen in the ore combines with carbon monoxide released from the fuel and is expelled as CO2. What is left is iron. The blast furnace’s height lets the rising gases preheat the ore and gives the iron more distance to descend as it softens – so it absorbs more carbon from the fuel. Because iron’s melting point falls as its carbon content rises, the iron becomes fully molten. A calcium-based “flux,” usually limestone, is added. The flux combines with impurities in the ore and forms slag. The ResourcesThe basic ingredients of iron making – iron ore, limestone, and carbon fuel – are some of the most common on Earth, but are not found everywhere. Early furnaces were built where these materials were available. The ProcessIron plantation life revolved around the always-running, roaring furnace. It shut down usually once a year – to refurbish its inner walls and hearth. While it was in “in blast,” its cycles of filling and tapping set life’s rhythm at Hopewell. It demanded close attention. Workers constantly fed it, watched its flame, and listened to the sound of its blast. For workers around the furnace, it was a hot, hard job requiring protective shoes and aprons. Every half-hour fillers dumped into the tunnel head 400 to 500 pounds of iron ore, 30 to 40 pounds of limestone, and 15 bushels of charcoal. With no gauge, the founder used his practiced eye to judge the shape and color of the flame from the chimney and the color and consistency of molten iron. This told whether the temperature was right and the proportions of ingredients correct. In temperatures that could reach 3,000°F, the molten iron flowed down toward the hearth, to be tapped when the founder judged it ready. At Hopewell, he generally tapped the furnace every 12 hours, at 6 am and 6 pm. After the guttermen drew off the slag, the iron could be tapped in two ways. It could flow directly into the “pig bed” in the cast house floor (it looked like a litter of nursing pigs), where it hardened into pig iron ready for market. Or it could be tapped into large ladles, the cast in molds. This process was repeated twice daily as long as the furnace was in blast.

NPS Photo The ProductTo make the most money from molten iron you would cast finished products at the furnace. Moulders cast several items: plowshares, pots, sash and scale weights, cannon, and shot. But as iron stoves grew more common in 1800s homes, Hopewell built its operation on stove plates. |

Last updated: August 4, 2025