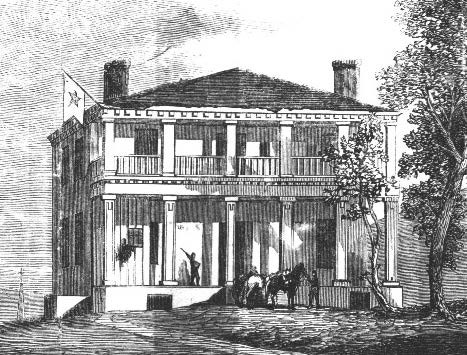

NPS/volunteer H. Mills The walls of the Lockwood House enclose a perfect storm of American history. From the Federal armory and its slave-owning officers, through the conflict of the Civil War, Reconstruction and the struggle to educate African Americans in post-war America, through the dramatic events of the first decades of the 20th century, to the unanticipated effects of the 1954 Supreme Court decision to desegregate education, there are within the walls of Lockwood House many stories to tell. Behind the ScenesLockwood House Virtual TourUS Armory and Arsenal Paymaster Residence (1848-1861)Lockwood House was originally built in 1848 as housing for the Paymaster of the United States Armory and Arsenal. This new nine-room house became the residence of Paymaster Edward Lucas and his family by December 1848. The Lucas household included five children, although an infant died before 1850. In addition to the Lucas family, the house accommodated one enslaved woman and two enslaved children. Mrs. Lucas died on September 1, 1849. Edward Lucas remained in the house until he died in 1858. That year, an entire story was added to the house, constructed more modestly than the first.

NPS photo Civil War (1861-1865)During the Civil War, Union and Confederate troops alternately occupied the house. The elaborate two-story porch became an ideal site for a base hospital during the summer of 1862. Labeled the "Clayton Hospital," the large rooms, high ceilings, and airy porch offered a healthy environment for soldiers suffering from camp diseases like dysentery, diarrhea, and various fevers. Wounded Union soldiers were also treated here during the Battle of Harpers Ferry in September 1862. Reconstruction and the Establishment of Storer College (1865-1883)By the fall of 1865, Lockwood House operated as a mission school and living quarters for formerly enslaved men and women run by Reverend Nathan Brackett, a Freewill Baptist minister working with the American Missionary Association and the Freedmen’s Bureau. In 1867, the property began operations as part of the Storer College Normal School, one of the first institutions of higher learning for African Americans in the United States.'

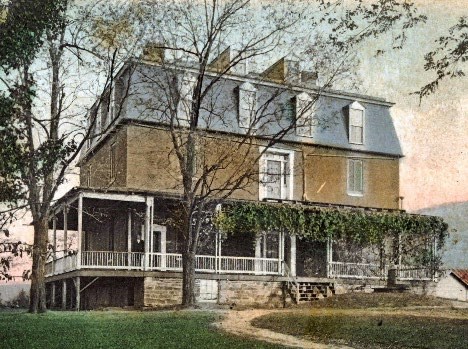

NPS Expansion and Multiple Use (1883-1960)By the early 1880s, Lockwood House served as a boarding facility for both Black and white summer tourists, and two additional stories were constructed to increase room capacity. This provided additional income for the College.

HABCS WVA, 19-HARF, 14-12. Lockwood House as Part of Harpers Ferry National Historical ParkIn the late 1960s, the NPS restored the exterior of Lockwood House to the Civil War period, removing the 1880s additions. In the interior, the NPS rehabilitated the lower floor and restored two rooms to the circa-1867 period. The remainder of the first and second floor were left as-is. Behind the ScenesLockwood House Virtual Tour |

Last updated: December 21, 2022