NPS The Escalante River traverses some of the finest canyon country of the Colorado Plateau and offers river-floating enthusiasts the opportunity to enjoy magnificent, wild, redrock canyon scenery. Because it is rugged and remote and sustains only limited flows, the Escalante River also provides unique challenges to the river runner. The deeply entrenched, meandering Escalante River flows between towering cliffs of red and white sandstone decorated with colorful desert varnish. Above the canyons lie rounded sandstone domes, buttes, and slickrock. Along the river lush riparian ecosystems, provide habitat for numerous plants and animals. Historic River ExpeditionsMembers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were the first Anglos to enter the upper Escalante drainage. They called the area "Potato Valley" in honor of the wild tubers they found growing there. Some members of John Wesley Powell's 1872 survey expedition explored the region. The group named the stream the "Escalante River" to honor Father Escalante—one of the leaders of the 1776 Dominguez-Escalante Expedition that searched for a trade route from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Monterey, California—despite the fact the father never actually saw the river. In May 1948, famed river runners Harry Aleson and Georgie Clark made the first recorded float trip down the Escalante River in a small Navy surplus neoprene raft. According to Aleson's journals, the trip was an ordeal. It took them seven days to push, pull, portage, tow, and (sometimes) float their way to the Colorado River, but they felt the scenery repaid them for their efforts and damaged equipment.

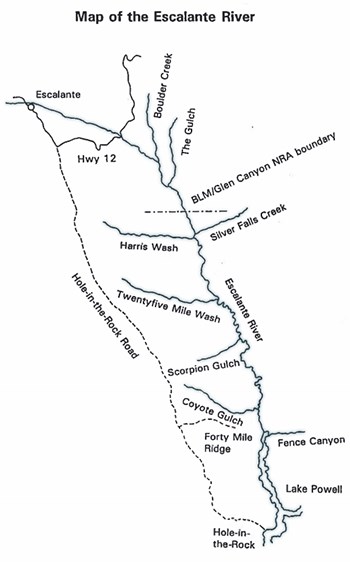

NPS The ChallengeEven with the right equipment, the Escalante is a marginal river for floating. In years with a good snowpack, the river may be navigable for up to two months during late spring or early summer, but in dry years it may not be floatable at all. An average year usually provides two or three weeks of run-able flows. Predicting when the runoff will peak is extremely difficult. According to U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) river gauging data taken since 1912, the average high water date is May 9th. However the runoff may begin any time from late March to early June, depending on snowpack and spring weather conditions. Consequently, the first challenge is having great flexibility in taking vacation time, the ability to travel on short notice, or amazing luck when planning vacation dates! A minimum of six days is recommended to complete the trip from the Hwy 12 Bridge to Coyote Gulch. Shorter trips linking alternative canyons are possible with light weight packrafts. WatercraftA narrow, shallow-draft boat is essential for floating the Escalante River. A short craft is desirable considering the many tight turns which have to be made. Inflatable kayaks and packrafts prove to be the crafts best suited for these conditions. Though several successful trips have been made on Stand-up paddleboards (SUPs), the passenger is rarely standing up. Hard shell kayaks can work well, but the trip often requires a great deal of getting in and out of the boat to avoid obstacles and getting stuck on rocks. Boat weight is a consideration. Choose a boat which can be easily carried. At least one, and possibly more, portages are required. Unless arrangements have been made for a powerboat pick-up at Lake Powell, the boater will be faced with a strenuous take-out. Stream flows may drop off suddenly, requiring river runners to push, tow, or even carry their boats. Therefore, it is best to choose a craft which is light and maneuverable for both the float trip as well as the hike out. River RatingThe Escalante River is a Class II river, but considering its remoteness, potential for severe equipment damage or failure, and limited escape routes, river runners should have at least Class III skills. Wave trains can form in higher flows, particularly in the lower canyon. The Escalante requires constant awareness and the technical ability to avoid obstacles, stay in the deepest part of the channel, and navigate tight turns. Boaters are often completely exhausted at the end of their trip. AccessLaunchThe most commonly used launching point is at the junction of Highway 12 and the Escalante River, 14 miles (22.5 km) east of the town of Escalante, Utah at Escalante River Bridge Trailhead. This trailhead parking lot becomes easily congested, and river runners are asked to park a minimum number of vehicles there. On the south side of the bridge is a pull out on the side of the highway that provides access to the river for unloading gear, rigging and launching. The distance from the bridge to Lake Powell is approximately 76-82 miles (122-132 km), depending on current lake level. Take-outThe most commonly used take-out point is at the confluence of Coyote Gulch and the Escalante River. The route exits the canyon via Crack-in-the-Wall and provides access to Fortymile Ridge Trailhead. This is a strenuous hike of 3½ miles with an elevation gain of almost 1,000 feet. The route is not marked, so it is wise to be familiar with the route and to carry a map. Four-wheel drive is sometimes needed to reach Forty Mile Ridge Trailhead, located off Hole-in-the-Rock Road. A 50 foot length of webbing is required to haul packs at the Crack in the Wall feature. Webbing does not scar the rock like rope. The only way to avoid the strenuous take-out routes at Crack in the Wall or another side canyon is to arrange for a powerboat pick-up on Lake Powell. If you do not know anyone with a powerboat, shuttle services are offered by a park concessionaire. For more information call the Bullfrog Marina at (435)684-3062. VariationsThe development of the lightweight packraft has opened multiple options for launch and take-out locations with-in the Escalante corridor depending on the visitor’s willingness to carry their gear for longer distances. Trips of this nature should pay extra attention to route finding, route conditions and potential technical obstacles for their given entrance and exit routes.

NPS SafetyAll river runners must have Coast Guard-approved personal flotation devices aboard their craft—one for each person. Inflation pump, patch kit, and spare paddle are essential. Helmets and glasses are strongly recommended as the floatable current often sweeps boats under overhanging limbs. Flash FloodsFlash flooding can result from heavy rains and thunderstorms. At the first sign of possible flooding, get off the river and ascend to higher ground with all of your equipment. Debris such as rocks and logs, carried by floods, in addition to the high volume of water, can present significant hazards. Flash floods usually subside in a few hours. Be patient and wait them out. Do not attempt to “ride the wave”! Debris, moved by flash flooding, can cause “strainers” in the river. Be alert! Backcountry PermitsBackcountry permits are required for all overnight stays in the Escalante District of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Obtain permits at Escalante Interagency Visitor Center in the town of Escalante or at one of the entry trailheads. These permits help us gather statistics on visitation and provide valuable information if a rescue becomes necessary. Group Size LimitLarge groups create large impacts. The Escalante River group size limit is 12 people. Groups larger than 12 people must break up into smaller groups and maintain a minimum distance of ½ mile from each other while floating and camping. Group size limits are strictly enforced. Leave No TraceMake every attempt to leave the backcountry nicer than you found it. “Take only pictures and leave only footprints” is a good reminder. Do not remove anything from the canyon. Leave the flowers, rocks, and everything else for others to enjoy. The best campsites are found, not made. Camp on durable surfaces and avoid trampling the vegetation and biological soil crust. Carry all of your trash out of the canyon, including toilet paper and other hygiene items. Do not burn or bury it. River runners are also responsible for their own equipment repairs and must not abandon damaged gear or equipment! Human Waste DisposalHuman waste must be removed from the river corridor within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (boundary is 3 miles below Horse Canyon). Because of the increase in recreational use, the National Park Service introduced a human waste disposal program in the Escalante River corridor and its tributaries within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Specifically designed waste bags are permitted for this purpose, but a dry bag or pvc “poop tube” is recommended to carry used bags to protect the health of river runners and the environment should a boat capsize. Use of a plastic or paper bag as a receptacle for solid human waste and/or for disposal of solid human waste is prohibited unless part of a specifically engineered bag waste containment system containing enzymes and polymers to treat human solid waste, capable of being sealed securely and state approved for disposal in ordinary trash receptacles. There are many “portable toilet” human waste bags available on the market. Some examples are Restop II Bags, Cleanwaste Bags and Biffy Bags. These products can be found at many outdoor product retailers. A self-contained, sealable, river toilet or “groover” also works as a heavier option. Visitors are responsible for providing their own removal system that is adequate for the size of their group and length of stay. Within Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, all backcountry users are required to use portable, self-contained human waste management systems within 300 feet of any water source. FiresFires are not permitted in the Escalante River corridor or any of its tributaries. Fireworks are prohibited. PetsPets must be leashed within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Pets are not permitted in Coyote Gulch. Boaters exiting through the Crack in the Wall may not travel up Coyote Gulch with pets above the Crack in the Wall route. Pet excrement within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area must be removed and disposed of in the same manner as human waste. WildlifeDo not feed wildlife. Food and trash should be stored in a manner impervious to entry by birds and other wildlife. Rock CairnsDo not build rock cairns. They can mislead other visitors and cause resource damage to build. Rely on your map and compass and know your route. There are no maintained trails. Preserve the SoundscapeYour voice carries farther than you think in canyon country. Respect other visitors by keeping your group quiet and not playing amplified music. If you must have music in the backcountry wear headphones.

NPS Graphic River DescriptionCheck Escalante River flow at the Utah Streamflow Table on USGS website. The site provides gauge depth and cubic feet per second (CFS) readings. The official recommendation for attempting an actual “float” trip on the Escalante is 50 CFS. Lower flows mean that one will have to spend more time out of the boat, pushing, pulling, and lifting the craft over rocks, sandbars, and riffles. Higher flows mean quicker float times but can create problems in navigating through tight boulder jams and chutes with swiftwater. It is important to be aware of the current flow, prepare for fluctuations during your trip, and to adjust your expectations. Please note: all listed river mileages are approximate. Highway 12 Put-in to Boulder Creek: 6 miles (9.6 km). Many small rock fields and gravel bars may result in frequent grounding, especially at lower water levels. Because of the many small bends in the river, the actual mileage may be more than six miles. Remnants of fences may be encountered along this section. Boulder Creek to The Gulch: 9.5 miles (15.2 km). The addition of Boulder Creek often doubles the volume of the river, but floating conditions may not necessarily improve for several miles. As its name implies, many volcanic boulders have washed down Boulder Creek from basalt fields at higher elevations. Consequently, fields of small rounded boulders may be encountered and may create obstructions at lower flows. They gradually subside farther downstream. The Gulch to Harris Wash: 14 miles (22.5 km). The trip becomes easier through this section, but at lower flows, gravel and sandbars will be apparent. About ¼ mile below The Gulch, just before the river makes a hard left, watch for a spring coming out of the right wall a few feet above river level. This is a handy "drive-by" spring at which one may obtain excellent drinking water. (All collected water should be treated before drinking.) At mile 21.5 (about 3 miles downstream from Horse Canyon), the river crosses the boundary into Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. The boundary is not marked. For the remainder of the trip, solid human waste removal is mandatory. Horse Canyon and Silver Falls Creek, both entering from the east, offer nice day hikes. Harris Wash to Twentyfive Mile Wash: 13 miles (21 km). No major difficulties should be encountered in this section, but at lower flows gravel and sandbars and occasional rocks and boulders will keep the river runner busy. Harris Wash, Fence Canyon, Neon Canyon, and Twentyfive Mile Wash all afford exploration possibilities. Twentyfive Mile Wash to Scorpion Gulch: 12.6 miles (20.3 km). Here the canyon walls are higher and narrower. This is perhaps the easiest section of the river to navigate. Scorpion Gulch to Coyote Gulch: 20.5 miles (33 km). About ½ mile downstream from Scorpion Gulch is a spring on the right which provides good drinking water. Here, the river has cut down into the softer Chinle formation. Since the Chinle erodes more easily than the harder Wingate sandstone above it, the Wingate formation becomes undercut, and huge blocks collapse and fall. These boulders litter the slopes below and fall into the river, creating boulder jams and rock fields. It is through this section of the river that inflatable kayaks or other short, durable boats are recommended. The first boulder jam occurs about a mile below Scorpion Gulch. Depending on the river flow and river runners' skill level, this jam may be run with a few tight turns. It is best to scout the run beforehand. The boulder jam can be scouted from either the right bank or the left bank, but the right bank is probably best. For the next 19 miles, the boater must constantly contend with rock fields, tight turns between and around boulders, and gravel beds. Constant attention is required to stay in the deepest part of the channel, elude obstacles, and avoid getting stuck, being swept sideways, swamping, or capsizing. Dry bags are a must and “rig to flip” to prevent losing gear. One boulder jam about 9.5 miles below Scorpion Gulch must be portaged. There the river funnels through a chute too narrow to run, but the portage on the left is fairly easy. Coyote Gulch to Lake Powell: 6-8 miles (9.6-12.8 km), depending on the lake level. Due to siltation from high lake levels, the river broadens as it traverses these mud deposits. At low flows, the river becomes braided, and it can be difficult to find a channel deep enough to float in. If this is the case, river runners traveling all the way to the lake may find themselves towing their craft through muddy water and quick sand. Between Coyote Gulch and Cow Canyon, several springs flow from both sides of the river. |

Last updated: April 17, 2025