|

Nonnative aquatic species are exotic species, including plants, animals, fish and microscopic organisms, which have been introduced from other parts of the world to a body of water. Some nonnative aquatic species are relatively innocuous and do not compete with native species, such as Asian clams (Corbicula fluminea) which are actually eaten by the common raven (Corvus corax) and ring-billed gull (Larus delawarensis). Many others are successful at spreading and invading an area, disrupting its ecology by outcompeting native species, disrupting food chains, and changing nutrient cycles. Without natural checks on populations, invasive nonnative species thrive and can dominate an area. These changes can be harmful to the ecosystem and local economy.

NPS Introductions of nonnative aquatic species can occur accidentally or intentionally. Human activities are often responsible for unintentional releases or escapes. The ballast water of transoceanic cargo ships often carry aquatic “hitchhikers” and contribute to the spread of nonnative aquatic species, including the introduction of the quagga and zebra mussels (Dreissena spp.) to the United States. Recreational activities, such as boating which is popular on Lake Powell at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (NRA), also contribute to this spread. Zebra mussels were discovered near the Great Lakes in 1988 and quagga mussels reached Lake Mead in 2007 presumably by boat. Occasionally some nonnative species are intentionally released to control other introduced species, though control is often difficult to achieve. Nonnative aquatic species can reduce sport fish populations, ruin boat engines and equipment, make lakes and rivers unusable by recreationists, reduce native species, degrade ecosystems, affect human health, dramatically increase the operating costs of industrial plants, power plants and dam maintenance, and impact local economies. The spread of these harmful species can be prevented by properly cleaning and decontaminating vessels and equipment before moving between bodies of water. All boaters should clean and dry their equipment after each use as described at www.protectyourwaters.net.

NPS New Zealand mudsnails (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) New Zealand mudsnails are native to the fresh waters of New Zealand and its adjacent islands, but have spread to three continents over the last 150 years. These small snails are about three to six mm (one-eighth inch) long and have are brown to black cone-shaped shells with five whorls. They were first discovered in the late 1980s in Idaho's Snake River and Montana's Madison River near Yellowstone National Park and were later found in Owens River in California in 2001. They are currently found in the Colorado River below the Glen Canyon Dam. These small snails are able to reproduce quickly and asexually, and are able to survive harsh, variable conditions. New Zealand mudsnails disrupt the food chain by consuming algae and competing with nonnative invertebrates. Because of their ability to reproduce asexually and create high densities, these snails are especially difficult to control once they enter a body of water. New Zealand mudsnails are most likely spread through human activities and are small enough that many water users may unintentionally transfer them. They can easily attach themselves to boots and waders, angling or sampling gear, and can be transferred in aquatic shipments. These tough snails can survive several days out of water.

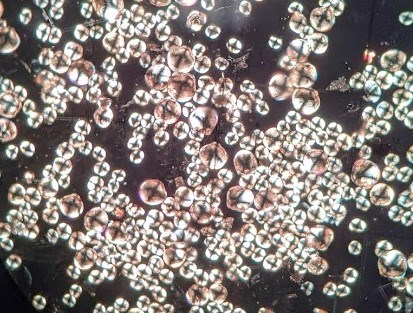

NPS Zebra and quagga mussels (Dreissena polymorpha and D. bugensis) Zebra and quagga mussels are native to Eurasia. They are extremely good water and food filters, removing large amounts of plankton and taking in pollutants which harm the wildlife that eat them. They compete with native species and clog pipes. They are believed to have entered United States in Lake St. Clair by the release of ballast water of ships from Europe and were first discovered in 1988. Zebra mussels spread rapidly across the United States and a related species, quagga mussels, reached nearby Lake Mead in 2007. Reproduction of quagga mussels was detected in 2012 and adult quagga mussels were discovered in Lake Powell in 2013. Quagga and zebra mussels are typically spread by vessels which have been in an infested body of water and have not been dried completely or decontaminated before entering another body of water. Quagga mussels are present in nearby Lake Pleasant, Canyon Lake, Lake Mead, Lake Mohave, and Lake Havasu. They are also now in Lake Powell. State laws require boaters take steps after using infested waters.

Nonnative Fish Nonnative fish species were introduced to the Colorado River prior to the completion of the Glen Canyon Dam in 1963. Walleye (Stizostedion vitreum), bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), green sunfish (L. cyanellus), European carp (Cyprinus carpio), and channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) are present in Lake Powell and developed from stock already present in the river system before the dam was completed. Some nonnative fish were unable to survive the environmental changes caused by the filling of Lake Powell. These fish, which include the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas), mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis), and plains killifish (Fundulus zebrinus), are still present in Glen Canyon NRA, but are now mainly found in the flowing rivers, inflows, and small perennial tributaries. Red shiner (Cyprinella lutrensis) established a marginal population in Lake Powell, but are more commonly found in flowing water. Smallmouth bass (Morone dolomieu) and striped bass (M. saxatilis) were introduced to Lake Powell because of their preference for open habitat and now dominate the fish community. Other nonnative fish, such as largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) and black crappie (Poxomis nigromaculatus), were introduced to Lake Powell to provide outstanding recreational sport fishing opportunities. To provide additional forage for these sport fish species that live in the upper layers of open water, threadfin shad (Dorosoma petenense) were introduced in 1968. Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) were stocked in the water released from the dam in the Lees Ferry area. Though native fish species were declining prior to the construction of Glen Canyon Dam, nonnative fish compete with and predate on native species. With proper management and planning, Glen Canyon NRA can preserve the remaining unique native fish and provide excellent recreational sport fishing opportunities of nonnative fish. Gizzard shad (Dorosoma cepedianum) Gizzard shad were unknown in Lake Powell until 2002 when six were documented in the San Juan arm. They are currently found all over Lake Powell and have no natural predators. Gizzard shad grow quickly and get bigger than threadfin shad (Dorosoma petenense). This rapid growth means largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) and smallmouth bass (M. dolomieu) are only able to prey on gizzard shad for a short time. Eventually, gizzard shad may compete with young bass for the same limited planktonic food sources. When the threadfin shad population declined in 2006 as a response to heavy predation from huge numbers of adult sport fish, the gizzard shad adult population continued to grow. Due to the suitable habitat available and implications of gizzard shad in Lake Powell, this species will affect the management and planning of recreational sport fishing opportunities of nonnative fish in Glen Canyon NRA. Bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) Bullfrogs are native to eastern and central North America, though they are now found throughout the world and western United States, including the Hite area of Glen Canyon NRA. They were accidently introduced through trout stockings, aquarium trade, and pest control. In 1898, they were imported to California for their legs. In the absence of natural predators like large water snakes, alligators, and snapping turtles and fish that eat their tadpoles, bullfrogs are able to outcompete (and eat) just about every small animal. Bullfrogs will eat almost anything they can fit in their mouth: birds, rats, snakes, lizards, fish, and other frogs including bullfrogs. Female bullfrogs lay about 20,000 eggs at a time, which are rarely eaten by native fish in the area due to their preference for native tadpoles. Because of the lack of predators, many of these young survive, providing an abundant food source for adult bullfrogs. Bullfrogs are also able to travel great distances, especially during wetter years. Whirling disease (Myxobolus cerebralis) Whirling disease is caused by the relationship between a parasite native to Eurasia and a common aquatic worm. The parasite was introduced accidentally to the United States in the 1950s and impacts trout and salmon. It penetrates the head and spinal cartilage of trout and is able to multiply quickly. This causes deformities and puts pressure on the organ of equilibrium which causes the fish to swim erratically (whirl) and have difficulty feeding and avoiding predators. Fish can reproduce without passing on the parasite to their offspring. When an infected fish dies, thousands to millions of parasite spores are released into water. These spores may eventually be ingested by the tiny, common aquatic tubifex worm (Tubifex tubifex), which will again infect trout with the parasite, continuing the life cycle. Whirling disease is especially difficult to destroy; it can withstand freezing and drying out, and is able to survive in a stream for 20 – 30 years. It is easily transported unintentionally by humans, animals, and birds. The decline or loss of recreational fishing opportunities due to whirling disease can negatively impact local and state economies. Whirling disease threatens the Colorado River below the Glen Canyon Dam. The spread of this disease can be prevented by never transporting live fish from one body of water to another, properly disposing of fish entrails and skeleton parts, not using trout, whitefish, or salmon parts as cut bait, rinsing all mud and debris from equipment and wading gear, draining all water from boots, and saturating boots and gear with a quaternary ammonium or chlorine solution. Decontamination details are available from www.protectyourwaters.net. Revised 3/23 |

Last updated: March 3, 2023