NPS/Stephanie Metzler Visitors to Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (NRA) may be surprised to learn just how dry the Colorado Plateau region is. The central Colorado Plateau region, which includes Lake Powell and surrounding land, is in a rain shadow, or region of reduced rainfall caused by the protection of mountains to the east and west. Page, Arizona, located near the Glen Canyon Dam, only receives 6.46 inches of rain annually, which is less than Phoenix situated in the Sonoran Desert. Precipitation is bimodal, with a late summer – early fall peak and a late winter peak. Between November and May, storms move into the area from the Pacific Ocean. During Arizona's monsoon from July to September, storms move northwest out of Mexico. Although most precipitation is in the form of rain, winter storms occasionally bring snow, especially at higher elevations in the area. The driest month is June, and the wettest is typically October. Average monthly temperatures vary from around freezing in the winter to 75°F in July. The record high for Page is 111°F, recorded on July 9 and 10, 2021. However, humidity is typically very low in the region, and thus hot days are not as uncomfortable as they can be in more humid regions.

Climate Data In and Around Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

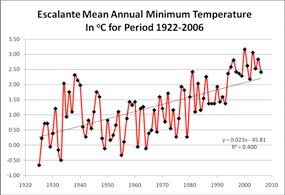

Thunderstorms are common during the monsoon in July and August and can sometimes be violent, with lightning, high winds, and heavy rains. These storms can create hazardous conditions including large waves on Lake Powell and extensive flooding in side canyons. However, these storms typically only last an hour or two. When storms are in the area, caution should be used when hiking in side canyons, as dangerous flash floods can suddenly appear. If storms threaten on Lake Powell, move into sheltered bays to avoid high winds and waves. The climate of the region is dynamic and has varied from cool wet phases to dry warm phases. Factors influencing these phases include the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), which typically has a 20 year cycle, and the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO), which has a 50-80 year cycle. El Niño-La Niña (EL-LN) events can also bring about dry and wet phases in the region. The summer 1983 El Niño event was one of the largest ever recorded and caused Lake Powell to rise so quickly that it almost overtopped Glen Canyon Dam emergency releases. The loss of the dam was prevented, but the bypass tubes were badly damaged. Drought, such as those in the 1930s and 1950s, is common in the region. Drought has gripped the American Southwest since 1999, with the driest year being 2002. In 2002, the Colorado River inflow to Lake Powell was 14% of normal, the lowest ever recorded. This year was the driest in the region since the ninth century AD. Studies have shown that drought can vary from a few years to 10 – 20 years, or sometimes as mega-droughts lasting 100 years or more. Drought cycles are also affected by the global warming phenomenon. With the steady increase of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the mean global temperature has been gradually increasing. This is particularly evident in the Arctic and Antarctic, where extensive melting has begun to occur in the last 10 – 20 years. In the Glen Canyon region, mean minimum temperatures have been increasing steadily since the early 1900s, as shown by the chart for the town of Escalante, Utah.

The interaction between EL-LN, PDO, AMO and global warming is extremely complex and not well understood. Earlier global warming computer models suggested that the Glen Canyon region would experience increased winter precipitation, bringing about a change in vegetation from desert shrublands to grassland or savanna communities. However, more recent models indicate that the region may become drier, with expanding desert vegetation and declines in piñon-juniper woodlands. This scenario has serious implications for the biodiversity of Glen Canyon NRA, especially as springs may begin to dry out and stream flows decrease. Many plants and animals are dependent on this water for survival, and their future may be jeopardized by climate change such as global warming. Some very recent studies also suggest that fire intensity and frequency may significantly increase due to warmer temperatures and earlier snowmelt and runoff. Published 8/07 More Resources

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Last updated: January 5, 2024