The American Fur Company Expands onto the Upper Missouri

John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company (AFC) built Fort Union trading post to make money from the plethora of pelts, robes, and other furs to be taken from beaver, bison (or buffalo), and other animals in the northern Rocky Mountains. England’s Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) operating to the north, in Canada, could not ship pelts, furs, and trade goods on the south-flowing Missouri River through Spanish, French, and, after 1803, American territory initially explored in 1804–1806 by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. That circumstance created a competitive opportunity for American fur traders. Soon after 1828, Fort Union dominated the Upper Missouri fur trade. The post’s founding bourgeois, or manager, AFC partner Kenneth McKenzie, solidified that dominance after 1832. That summer, McKenzie brought the first steamboat to Fort Union, a transportation innovation that revolutionized the fur trade. Transportation costs lower than the HBC’s meant the Upper Missouri Outfit, as the AFC’s western department was called, could pay more for furs than its Canadian competitor. With this advantage, the UMO convinced potential trading partners among the Blackfeet to trade with Fort Union instead of the HBC.

Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. 1985.66.407 Today, Fort Union’s legacies—and they are many—include the good, bad, and unforeseen. They are a testament to both human ingenuity and limitations: sage business acumen, entrepreneurship, and the devastating consequences of technological innovation and unanticipated variability in supply and demand as well as the environment. Fort Union and the AFC for a time succeeded in creating and supplying the demand for furs; in business, they out-competed their American and HBC rivals. That competition cost everyone, however, the traders and their American Indian trading partners. The fur trade succeeded so grandly that the Upper Missouri peoples and traders exhausted their supply of pelts and furs. The traders in the process introduced and, often unwittingly, spread diseases like smallpox that decimated their American Indian trading partners’ societies and lifeways. These effects, made possible with the tribes’ complicity, subsequently dispossessed the Upper Missouri peoples of their lands and game-dependent ways of life. It’s a story that still needs to be told. It’s one the tribes themselves need to be invited to share.

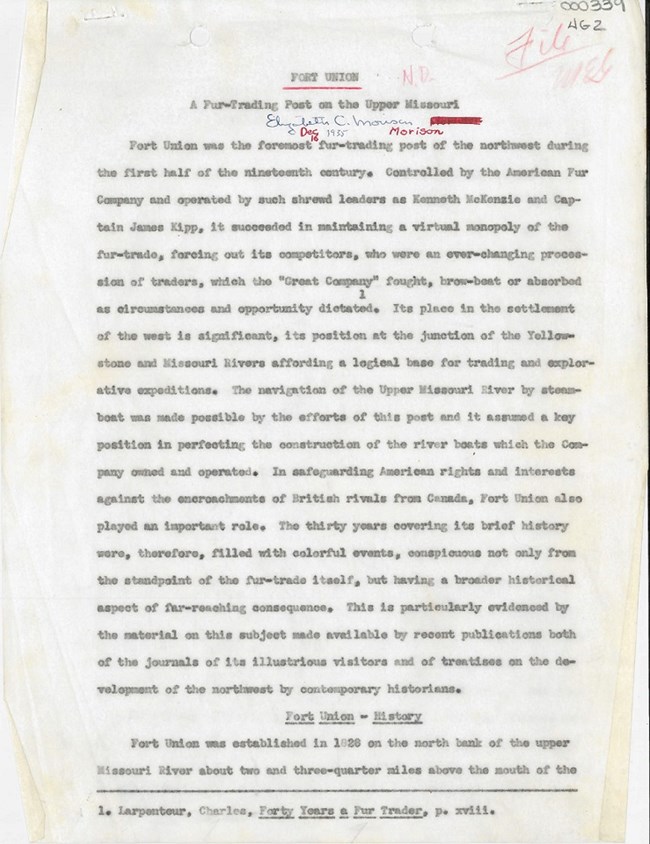

NPS Photo Its National SignificanceAs occurred in North Dakota, so too across America. Women especially invested time and money to protect and preserve local and nationally significant historic sites the likes of George Washington’s Virginia residence, Mount Vernon. Even Congress acted in 1935, when on August 21 it passed the Historic Sites Act. Authorized to aid State governments implement their historic preservation programs, the National Park Service (NPS) commissioned two studies of Fort Union trading post. Elizabeth Morison, a NPS junior historian, completed the first in 1935 to guide creation of a post diorama in Washington, D.C.’s Interior Department Museum. The second, written by a North Dakota native and NPS historian, Edward A. Hummel, concluded, “The associations of this post with the American Fur Company and the western fur trade, and the length of its existence, give to it a national historical significance as one of the most important American fur trading posts” in the country’s history. “If visitation would justify such extreme measures,” Hummel wrote, “the post could be reconstructed. Information for the authentic restoration can be secured from the excellent descriptions . . . found in the accounts of Audubon, Maximilian, and Kurz.” |

Last updated: April 24, 2021