|

By Josh Freeman, Park Ranger, Fort Necessity National Battlefield Why is the Fort so small?One of the most frequent visitor questions we receive at Fort Necessity is “is that the Fort?”. First time visitors find it hard to believe that the 53-foot diameter structure they view in the middle of the Great Meadows is George Washington’s “fort of necessity”. Perhaps the aptness of the fortification’s name is lost on them, for soon after many visitors will comment “the Fort is so small; Washington was so dumb.” Most casual visitors are confused about what they are viewing at Fort Necessity, their expectations upon hearing the term “fort” having led them to believe they would find some large, European-style castle like structure. Even amongst knowledgeable students of the French & Indian War, familiar with wilderness forts and field fortifications, the common theme is that George Washington was a young, naïve, inexperienced commander who made a militarily stupid decision in July 1754. He placed his “fort” in a low-lying area, surrounded by hills that commanded it, which allowed the French to fire into the fort with impunity and which led to inevitable disaster and defeat. But is this the clear-cut story of Fort Necessity? Is it really that simple?

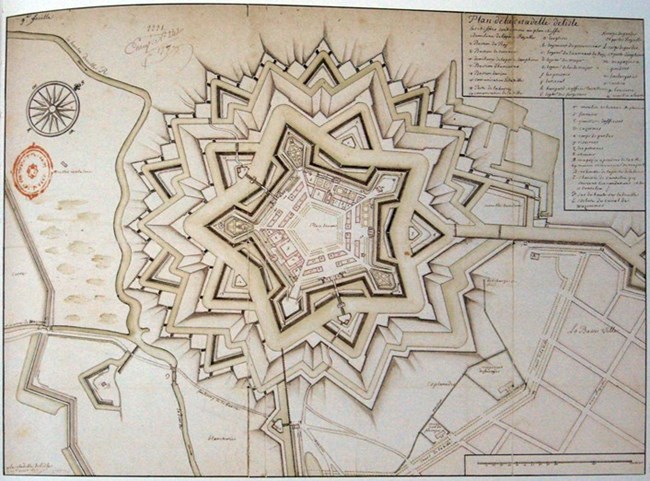

Larivière n.d. The Art of Fortification: The Geometry of WarBy the middle of the 18th century widely known and accepted practices for “modern” military fortification had been in place in Europe for nearly a century. Nearly all professional military officers were exposed in some way to what were considered the professional standards of knowledge relating to military engineering and fortification. The most influential figure during the development of the theory and practice of military engineering in the late 17th and early 18th centuries was Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban. Vauban, as Marshal of France under King Louis XIV, developed a system of attack and defense that became the standard throughout Europe. He built numerous forts and fortifications throughout France, which were quickly copied by other European powers. Vauban developed and standardized the best practices for the construction of military defenses. The pentagonal five bastioned fort, like the pictured in figure III, allowed the defenders to fire on attackers from all angles. Soon many of the larger cities of Europe, which served as supply points or magazines for operating field armies, began to construct defenses using Vauban’s system.

De l'attaque et de la defense des places. The Hague, Pieter de Hondt, 1737 The strength of the defenses designed by Vauban meant that it became very difficult and costly to capture them by force. Often a long siege would be required, whereby defenders would be starved or intimidated into surrendering. Siege warfare would emerge to be the predominant form of combat in Europe throughout the first half of the 18th century.

Vauban in 1670 Archives Nationales, Paris, France The necessity of understanding the science of how to construct both the defenses as well as the siege works to capture them necessitated ever increasing knowledge in the military art. Engineers, those officers specifically trained in the subject, became ever more valuable to armies as dynastic wars continued to rage across Europe. Specialized officer corps and schools began to develop that trained engineers, such as the British Corps of Royal Engineers in 1720 and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwhich in 1741. Engineers became an officer most commanders would not dare to be without on campaign.

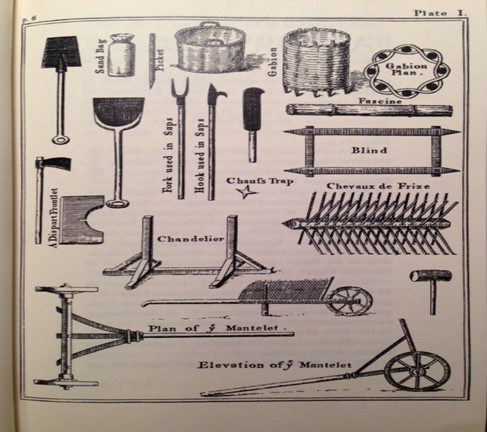

Engineering in the Forest: The Construction of Fort NecessityWhile the 22-year-old Washington was certainly no professionally trained military engineer, he was at least familiar with the basic math that went into their construction. His first job in life was a surveyor, so using a compass and theodolite were very familiar to him, as was measuring and laying out things. He was also familiar with the design and defense of fortifications. While visiting Barbados with his older half-brother Lawrence in 1751, Washington encountered one of the most heavily fortified locations in North America. Young Washington was always a keen observer, and he commented at length about the island’s defenses, especially Charles Fort . Washington also had numerous military manuals available to him. While it is unknown what or even if Washington had manuals with him on the Fort Necessity campaign it is likely that he at least had a knowledge from, or a copy of, Humphrey Bland’s Treatise of Military Discipline, the bible of the British Army . At least one of Washington’s officers had a copy of Bland with him on the 1754 campaign. Bland’s treatise contained several sections on field fortifications . Bland’s manual, like many others of the period, borrowed heavily from the engineering and fortification principles espoused by Vauban and other early visionaries. As Washington’s little army proceeded into the wilderness in 1754, he knew he needed and was prepared to build fortifications . In fact, his main mission was to build a road and support the fort-building operations already ongoing at the Forks of the Ohio , where the city of Pittsburg stands today. His orders from Governor Dinwiddie were “You are to use all Expedition in proceeding to the Fork of Ohio with the Men under Com’d and there you are to finish and compleat in the best Manner and as soon as You possibly can, the Fort w’ch I expect is there already begun by the Ohio Comp’a” (Captain Trent). He brought with him tools, like those pictured in Figure IV, to build fortifications and blacksmiths to repair old tools and build new ones.

Both European powers understood that forts in the wilderness would not be on the grand scale of their counterparts in Europe. Their remoteness made them expensive to build and maintain, and it was very difficult and costly to resupply them. Only a small number of troops could be kept in garrison for long periods of time. The smaller the garrison, the smaller the fort. They were built to size, so that the number of defenders could man each point within. The defenses of fortifications were also designed based on the types of threats they might face. Fort’s near the coast might expect an attacker to be armed with heavy artillery, such as siege mortars or howitzers, or even to be bombarded from ships naval guns. However, fort’s in more remote wilderness areas might only face small arms or light artillery. The threats they might face also factored into what type or size of fortification would be constructed. What is an Earthwork? The Lost Defenses of Fort NecessityWashington expected a quick French response to the Jumonville incident. When that did not come, he decided to continue his movement to the west toward Redstone (Brownsville, PA). He planned to build the road to Redstone, there construct a fort surrounding a pre-existing Ohio Company storehouse and await his promised reinforcements and supplies . On June 16th Washington’s force left the Great Meadows, now reinforced to approximately 300 men. Captain James Mackay’s 100-man Independent Company of British regulars, which had arrived on June 14th, remained behind at Fort Necessity . Washington was at Gist's Plantation (Mt. Braddock, PA) on June 29th when he received intelligence that the French at the Forks of the Ohio had been reinforced and were planning to march and attack him. Washington had originally planned to make a stand at Gist's, where a fortification was begun which was termed “the hog-pen fort.” However, a council of war on that same day determined the best course of action was to retreat. Listening to the unanimous advice of his officers, including the recently arrived Captain MacKay, Washington ordered the army to retreat to the Great Meadows. The exhausted and mal-nourished soldiers were forced to carry their provisions, ammunition, tools and even the nine 100-pound iron swivel guns back up and over Chesnut Ridge. Washington had sent all the horses back to the Great Meadows to hopefully hurry forward the supplies that were daily expected. Thus, with most of the horses gone, the men themselves were forced to carry all the equipment, stores and munitions. Washington paid some of the soldiers to carry his personal gear, as he had his horse loaded with ammunition. What could not be carried was buried. The army began its arduous and demoralizing retreat.

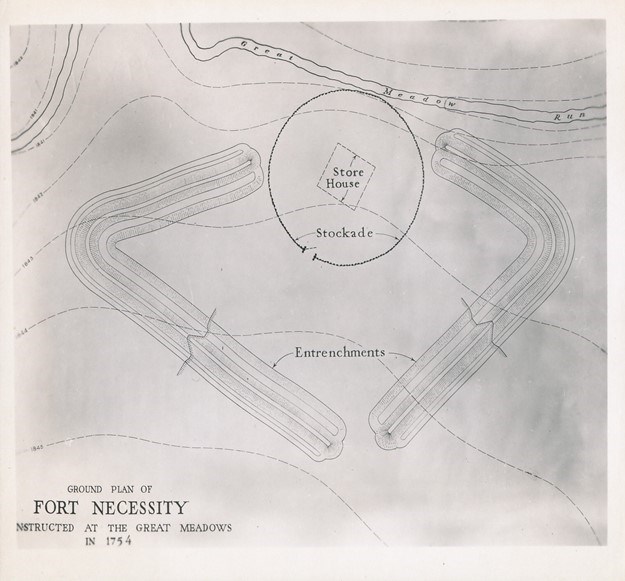

Eastern National The Great Meadows in the 18th century could be referred to as an oasis of grass in a desert of trees. And these were not small trees. The old growth virgin forest which surrounded the Great Meadows were giant trees, in some cases 8-10 feet in diameter, tress that had never been cut. Much like modern military principles, defensive works in the 18th century required open space surrounding them, allowing the defenders “clear fields of fire.” This was a space to kill the enemy before they could get to you. The only area in which Washington could establish a defensive position with enough clear space to build a fortification to house 400 men and still have clear fields of fire was the largest section of the Great Meadows. This is where he had already constructed his circular stockade redoubt. Washington decided to incorporate the stockade into the larger, expanded work.

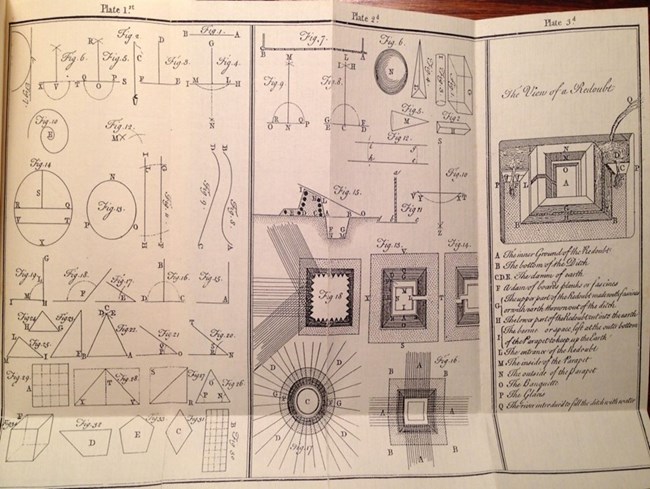

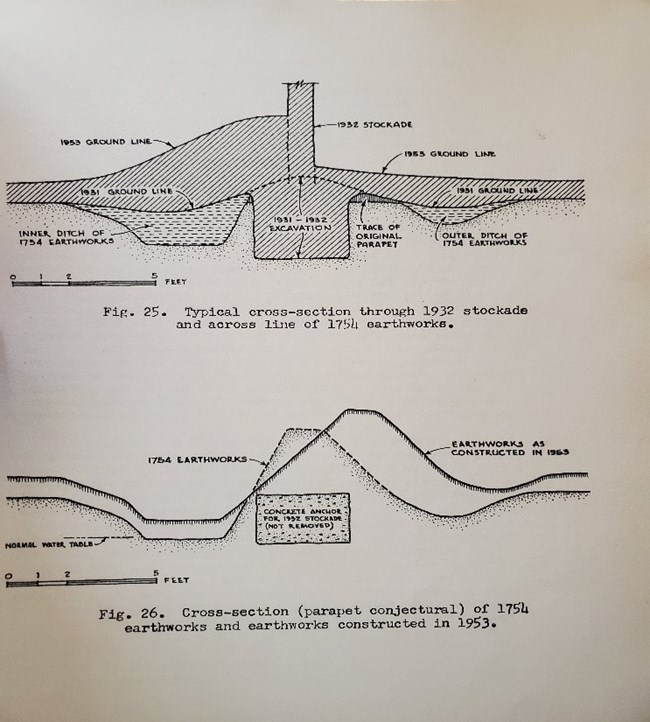

Eastern National With his limited resources, the young commander set priorities of work and put his men about constructing field fortifications to protect his 400 soldiers. It must also be remembered that the entire force would not have been available to work on the defenses. 18th century armies had daily tasks they had to accomplish, and Washington’s was no different. The young commander dispersed his men in groups out conducting reconnaissance, men on picket or guard duty providing security around the camp and men in various details and working parties, such as blacksmiths and bakers . Those men who were working on the defenses constructed two “fleches”, arrowhead shaped walls, viewed in Figure VI, which together formed a semi-rectangular redoubt of earth and wood. When determining the size of the redoubt, the officers used a well-known formula for constructing defenses. Military engineering manuals instructed officers that each file of soldiers needed a pace, or about two feet of space to load, maneuver and fire their musket. In defensive positions, British soldiers in the 18th century stood in two ranks, one behind the other. That meant Washington’s men, some 400 strong, only needed 200 men of frontage. 200 men, according to the formula, would need 400 feet of wall to fight from behind. If you measure the earthworks at Fort Necessity, they are almost exactly 400 feet in length. It is unknown who precisely supervised the construction of these defenses. Washington was certainly familiar with fortifications, and Captain MacKay was a professional officer with over twenty years of experience and had served in large forts in South Carolina and Georgia. Captain Robert Stobo later claimed to have been appointed “Regimental Engineer”, but there is no contemporary primary source evidence to support this . It is also unknown exactly how the walls were built. No specific contemporary description of their construction exists, but most likely one of the officers measured the angle of the fleches and laid out the line on which the walls, or parapet, were to be built. Then the men began by digging a ditch to serve as a trench on the interior of the line that was laid out, piling up the earth along the line itself. After digging about two feet they then dug a ditch on the exterior, again piling up the earth in the middle. JC Harrington’s 1953 archeology, seen in Figure VII, discovered the two-foot depth of the trenches. Two feet makes sense, as the water table would have been struck at that depth. The Great Meadows was an open grassy area precisely because it was a rather wet, sort of marshy place. After the parapet was constructed, logs were most likely used at certain portions along the wall, especially at the top, to hold down the earth and provide additional cover. There is some archeological evidence to support this. Eighteenth century military engineering manuals called for earthen redoubts to be built of gabionsfascines, baskets of wood and earth formed together into a wall. If time was not available to construct gabions then fascines, bundles of sticks bound together, were to be used . The British soldiers, although most likely familiar with gabion construction, did not have the time to build such formal structures and thus resorted to readily available and easily used material, dug earth and stacked logs. It is possible fascines were used, but no primary source or archeological evidence has been discovered to prove this. That the earthworks themselves existed is strongly supported by the historical record. Washington recalled that after first forming his men in the meadow in line of battle, his army soon “retired to our trenches” and that he was concerned that the French would endeavor to “force our trenches” by “their superiority of numbers” . Private John Shaw recalled after the battle that prior to the engagement the army “had endeavored to throw up a little entrenchment round them.” The wall was most likely about four feet high, or breast high on most of the men, hence the term breastwork that Major Stephen used . The two-foot ditch on the interior of the wall gave the soldiers standing behind it about six feet of cover. The longest section of the walls, the part which could fit the most men, faced the southeast and southwest, the direction that Washington knew the French would fight from . This was the area of the wood-line that came the closest to the fort and he had not had the time or resources to clear back farther. Those sections of the earthworks were also where Washington placed his most significant casualty producing weapons, two of his swivel guns. It was likely that the tops of the felled trees were linked together around the exterior of the earthworks to form an “abatis”, a primitive form of modern barbwire. It is unknown how the opening, or sally port, in the earthworks was secured. No archeological work has ever been done at that location. It may have been that, like most redoubts constructed during the period, a traverse, or small wall, was built on the interior of the opening to block incoming fire . Wagons or some other obstacle may also have been used to block the opening. Although not finished when the French arrived around 11am on July 3rd, Washington’s little fort was fairly well constructed. Even the French commander Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers noted that it “was advantageously enough situated.” De Villiers knew that he could not launch a frontal assault on the redoubt without “expos[ing] the subjects of his Majesty in vain.” The experienced French commander, a veteran of several decades of wilderness service, quickly realized that this fight would be a siege. His French marine infantry, Canadian militia and American Indian allies quickly surrounded the fortification, using the tree line for cover. An all-day fight ensued, with periods of shooting interrupted by periods of rainfall, some torrential. By nightfall, Washington’s force was wet, muddy and tired. Worse, they had suffered over 100 casualties, 30 dead and some 70 wounded. The trenches were filled with water, the men were having trouble shooting back because of fouled muskets and many of them had broken into the army’s rum supply and gotten falling-down drunk. To say the young commander had a few problems is an understatement. However, the French had problems of their own. Unbeknownst to Washington, de Villiers’s force was basically out of ammunition, low on food and were about to lose a significant portion of their force. It must be remembered that the French column had left Fort Duquesne on June 28th. It is unknown how many French soldiers and their allies were on the battlefield on July 3rd, 1754. The primary sources do not agree on the strength. Our best guess given all the accounts is around 700, approximately 500 French and Canadians and around 200 American Indians. De Villiers’s men had with them only the food and ammunition they could carry on their person. By July 3rd, having been on the march for six days, the French were running low on supplies. Regarding ammunition, the French commander noted that during the battle “the fervor and zeal of our Canadians and soldiers worried me because I could see we would soon be without ammunition” Just as troubling, de Villiers’s American Indian allies told him they were leaving the next morning. They reported British reinforcements were on the march and close by, which was not the case, and that they needed to head home. Some of the warriors of the pays d’en haut, tribes from the interior of Canada, had travelled from as far as the shores of Lake Michigan to be at the battle and were ready to return . De Villiers knew that to be victorious and accomplish his mission, he had to wrap up the engagement before his allies left. At around 8:00pm, de Villiers offered a ceasefire and generous terms for the British surrender. Washington, unaware of the French situation, was eventually convinced to sign. His reasons were many but consisted mainly of the fact that his force had suffered significant casualties and the men he had left were combat ineffective; either their weapons didn’t work, their ammunition was ruined, or they were drunk. His men were in bad shape even before the shooting started. He was very low on food, and resupply and reinforcement were nowhere to be found . Thinking he was heavily outnumbered, he made the most logical decision he could given the circumstances and the terms offered. Around midnight, Washington agreed to surrender Fort Necessity at dawn on July 4th, 1754.

National Park Service "I would not trade the discovery of Fort Necessity for a Pharaoh’s grave ship"The quote above was uttered by JC “Pinky” Harington, chief archeologist of the National Park Service, who was sent to Fort Necessity in the summer of 1953 to discover the truth about the fortifications size and location. For many years, since the reconstruction of the site in 1931-32, there had been a debate about the exact size, composition and location of Washington’s little fort . As constructed from 1932, a large rectangular wooden stockade wall greeted visitors to the site, as seen in figure VIII. However, all primary source accounts of Washington’s construction at the Great Meadows indicated a round structure.

National Park Service The first surveys conducted of the site in the early 19th century, with the wooden stockade no longer present, seemed to indicate a rectangular shape. The French had torn down and burned the wooden portions of the fort after they captured it . What early surveyors encountered were the only visible remnants of Fort Necessity left on the surface, the outline of the eroded earthworks. Not understanding what they were looking at, they took these outlines to be the remnants of the exterior wall of the stockade itself . Limited archeology in 1931 seemed to prove the rectangular theory . Harrington, after reviewing the primary source evidence, went to work in 1953 to prove which was correct. After digging numerous test pits and trenches, he quickly became convinced that the stockade portion of the structure had been round. Expanding on this theory, he began larger excavations and quickly proved himself correct. He found the burnt off stockade posts in the ground, arranged in a circular formation approximately 53’ in diameter. Harrington had found Fort Necessity.

National Park Service But what he also discovered around the stockade were the remnants of what he quickly identified as earthworks . Harrington and his workers found the remnants of the trenches that surrounded the wooden circular redoubt. From his archeology, Harrington believed that the majority of the earthwork’s parapet, or wall had been made of earth. He also discovered that the interior and exterior trenches were dug to about two feet each, the earth thus removed piled up in the middle to about the height of four feet . In one place, Harrington even found one of the logs he believed had been used to construct the earthworks (see figure X). ConclusionHopefully this brief examination has helped you understand that the story of Fort Necessity and the battle here, as well as the accounts of its participants, is far from black and white. There is very much a shade of gray to the story. It cannot simply be posited that the 22-year-old Virginia colonel was simply a young, dumb, naive kid who didn’t know what he was doing. In fact, there is much evidence to the contrary. Unlike Washington’s trenches during the battle, the popular perception of the young commander’s decisions simply doesn’t hold water. Upon closer examination, Washington on this campaign generally made logical decisions based on the conditions confronting him and his available resources. That he was inexperienced and to a certain extent unprepared for his first command is not really debatable. But, given the conditions and circumstances Washington faced, would another British officer have fared much better? There were more than a few regular British Army colonels in their early to mid-twenties. Which professional officer had they been plucked from Europe and deposited in the American wilderness would have achieved more? The answer, I would argue, is none. Washington faced daunting challenges in the 1754 campaign. An unexpected leadership role, untrained men, disgruntled officers, chronic shortages of food and supplies, rugged terrain, a vague understanding of his mission (especially after the Jumonville skirmish), lack of clear guidance from, and a remoteness to, his higher headquarters and Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie, an experienced and skilled enemy and many others. Yet the young officer accomplished a great deal. He moved his force over the mountains and into the wilderness, he built a road where one had not existed previously, he had made decisions when they were thrust upon him, he had looked out for the welfare of his officers and men where he could, he had built a defensive position that even his experienced adversary had remarked on admirably and he had led men gallantly in combat. He had begun to become a combat leader and had learned important lessons that would serve him the rest of his life. Bibliography and Suggested ReadingPrimary Sources Bland, Humphrey. A Treatise of Military Discipline, 7th Edition (London, T&T Longman, 1753). Brock, R.A., ed. The Official Records of Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant Governor of the Colony of Virginia, 1751-1758 (Richmond, VA: Virginia Historical Society, 1883). Cleland, Hugh, ed. George Washington in the Ohio Valley (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1955). Fitzpatrick, John C., ed. The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, Volume I (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1931). Kent, Donald H., ed. George Washington’s Journal for 1754 (Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical Association, 1952). Pleydell, J. C. An Essay on Field Fortification, Intended Principally for the Use of Officers of Infantry (London: J. Nourse, 1768). Russell, Samuel L., ed., Coulon de Villers: An Elite Military Family of New France (Savanah, GA: Russell Martial Research, 2018). Secondary Sources |

Last updated: November 12, 2024