“I feel I’d like to go off with you and forget the rest of the world existed.”Eleanor Roosevelt to Marion Dickerman, 27 August 1925 “I wish I could lie down beside you tonight & take you in my arms.”Eleanor Roosevelt to Lorena Hickock, 1 September 1934 “In the meantime love me a little and show it if you can and remember to take care of yourself for you are the most precious person in the world. All my love.”Eleanor Roosevelt to David Gurewitsch, 8 February 1956

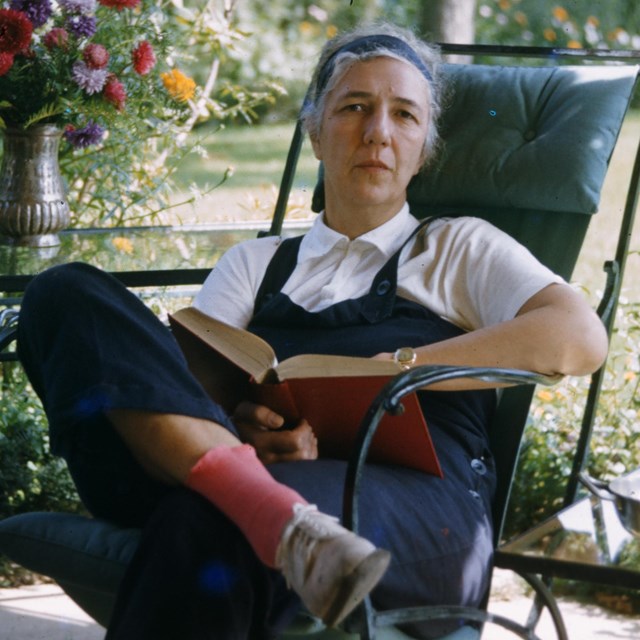

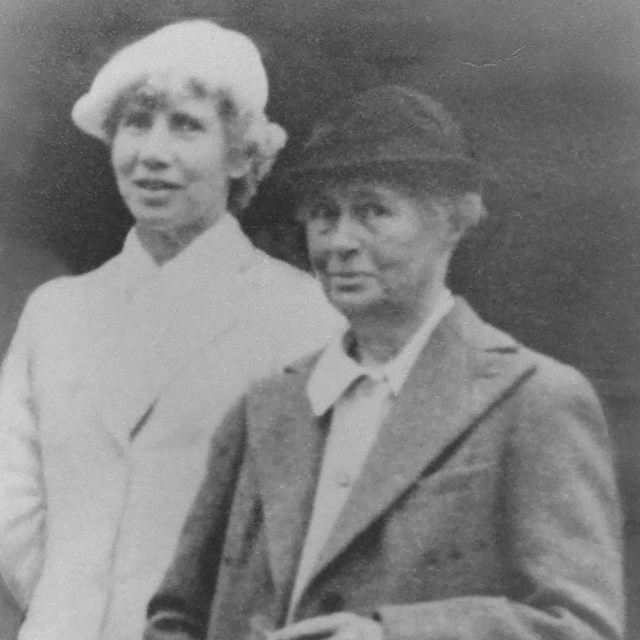

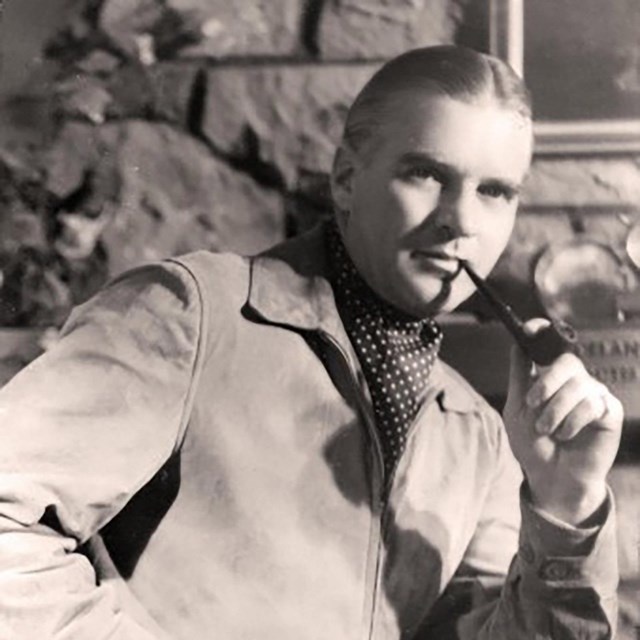

Eleanor Roosevelt, 1937. FDR Library Photo Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ)* people are part of the fabric of American life and history. The stories of their strengths and struggles—the right to live, love, and thrive—is a story of the cultural, social, and legal history of the United States. During Eleanor Roosevelt's lifetime, no lesbian, gay man, bisexual, transgender, or queer person gave a thought to their homes or actions being historic. Most were living their lives quietly or in secret. But at Val-Kill, LGBTQ people infused this place with meaning. Their lives and their work are fundamental to Val-Kill’s significance. Eleanor Roosevelt surrounded herself with influential women that today we recognize as lesbian. Several were life-long partners—Nancy Cook and Marion Dickerman, Molly Dewson and Polly Porter, Esther Lape and Elizabeth Read. These women enlivened Val-Kill as much or more than anyone else. Cook and Dickerman built Val-Kill with Eleanor and resided there for three decades. Lape and Read played an important role in Eleanor’s political development and activism. Eleanor had a lengthy and intimate relationship with journalist Lorena Hickok—their extensive and sensual correspondence is now well-known. Established as a National Historic Site in 1977, the romantic relationships of either Eleanor Roosevelt or Nancy Cook and Marion Dickerman were not acknowledged at Val-Kill. Cook and Dickerman were ambiguously described as life partners—end of story. Eleanor’s intimate life was the subject of rumor while she was living, the details obscure until the papers of Lorena Hickock were made available for research in 1978. Even then, the most romantic passages between Eleanor and “Hick” were dismissed as “particularly susceptible to misinterpretation.” The narrative at Val-Kill continued without recognition or exploration of Eleanor Roosevelt’s emotional and erotic life. Any resemblance of passion in the life of Eleanor was reserved for clichés—she was admired as an outspoken stateswoman who loved all people, championing their civil or human rights. Eleanor’s romantic affection was not limited to women. Her relationships with two younger men—Earl Miller and David Gurewitsch—were also among the most important of her life. Eleanor’s son, James, believed “there may have been one real romance in mother’s life outside of marriage. Mother may have had an affair with Earl Miller.” Without any surviving documents to characterize the precise nature of her relationship with Miller, it remains a mystery. In later years, friends referred to rumors that Eleanor wanted to leave FDR after his election to the presidency and marry Earl. Later, there was David Gurewitsch. Over the fifteen years she knew him, Gurewitsch was Eleanor’s friend, confidant, personal physician, traveling companion, and the object of an intense romantic affection. Among the hundreds of personal letters between them, many reveal the longing and tender, unrequited love of an aging woman in the twilight of her life. The absence of this history at Val-Kill has been a long-standing concern for LGBTQ people and scholars. The ambiguity of evidence, as is often the case with historic LGBTQ lives, has been championed as a rationale for denying the history. Today, a broader, more rich understanding of Val-Kill’s significance and meaning has benefited from LGBTQ scholarship and biographies published over the past twenty-five years. LGBTQ people are defined almost exclusively by their sexuality and gender expression usually marked by others as deviant behavior. Thus, historians tended to obscure this aspect of famous LGBTQ lives. But to ignore it, is in effect rewriting history by leaving out important aspects of their lives. Why should we care to know anything about Eleanor Roosevelt’s intimate life? Eleanor tells us herself, in a letter she wrote to Gurewitsch in 1948: The people I love mean more to me than all the public things even if you do think that public affairs should be my chief vocation. I only do the public things because I really love all people, and I only love all people because there are a few people whom I love dearly and who matter to me above everything else. These are not so many, and of them, you are now one. If we want to understand Eleanor Roosevelt, we cannot separate her public life from her intimate life. The opportunity to “love dearly” sustained the life of a compassionate humanitarian. In this way, Eleanor Roosevelt’s true legacy is really the freedom she gave herself to love. *The LGBTQ acronym has multiple forms. The Q generally stands for queer or questioning. Sometimes A (asexual), I (intersex), and + is added in recognition of all non-straight, non-cisgender identitites.

Now AvailableCourage to Love

|

Last updated: November 20, 2023