University of Virginia

Beatrix Farrand (whose maiden name was Jones) was born in 1872 in New York City to a wealthy family and spent her formative years among the upper crust of New York society. Her family was so fashionable, that it is said that the phrase “keeping up with the Joneses” was first used to describe them. Beatrix fell in love with plants at an early age. Trips to her family’s summer home on Mount Desert Island in Maine, as well as her family’s longtime love of gardening, inspired Farrand to pursue a career in horticulture.[1] Horticulture and landscape design, however, were not professions available to women at this time. Rather than take formal courses in the study of horticulture (she was unable to because she was a woman), Farrand spent a year as an apprentice to Charles Sprague Sargent, the director of Boston’s Arnold Arboretum in 1896.[2] She studied botany, surveying, and horticulture during her time with Sargent. Additionally, she hired a faculty member at Columbia University to provide her with more in-depth tutoring in surveying (Columbia prohibited women from attending such classes).[3] Her apprenticeship with Sprague and surveying studies were supplemented by a tour of foreign gardens that took her across Northern Africa and Europe. She was inspired by what she saw abroad, and upon her return, was poised to become one of the most influential garden and landscape designers of her time.

A professional study as intense as Ferrand’s was incredibly unusual for a woman of her background in this era. Farrand wrote that initially, “My friends looked upon my studies as a sort of mild mania...”[4] What was even more unusual was when Farrand opened her own landscape gardening firm in New York City in 1896 at age 23. At a time when women of her social set were expected merely to marry well, have children, and attend social gatherings, Beatrix Farrand’s foray into landscape architecture and gardening was radical. Through her wealth and privilege, she was afforded the opportunity to break new ground for women. In 1899, at age 27, she became one of the founding members of the American Society of Landscape Architects. She was the only woman in this group of eleven, which included perhaps the most famous American landscape architect of all time, Frederick Law Olmsted. As this group was the first to use the term “landscape architect” to describe the profession of designing and arranging landscapes, Beatrix Farrand can be considered the first ever female landscape architect, though she preferred the title “landscape gardener.”[5] Terminology, and technicalities aside, Farrand faced challenges being virtually the only woman in a male-dominated profession. She found it difficult to receive commissions to design public gardens because she was a woman, and her male colleagues often did not take her seriously. In fact, Frederick Law Olmsted once dismissed Farrand as “a dabbler”.[6] Thus, most of her commissions were to design private gardens for the homes of the Philadelphia, Boston, and New York elite.[7]

One of the earlier commissions she received for a private household garden was from her cousin, Thomas Newbold of Hyde Park, New York. Newbold had just hired the famous Charles McKim to renovate his home, “Bellefield.” Around the same time, he hired his cousin to design a garden that would complement McKim’s alterations to his home. Farrand laid out this garden in three “rooms” and in forced perspective, so that the garden appears much larger than it really is. She tailored this garden exactly to the Bellefield mansion, using the proportions of the living room as the starting point for her design. The garden’s paths also match up exactly with the edges of the mansion’s living room. Farrand’s garden at Bellefield contains many features that became trademarks of her work. Native and non-native species come together here, and plantings become more native and “wilder” the further they are from the mansion. Even the walls of the garden become wilder as it extends from the house, with hemlock hedges replacing stone. This technique of sequencing plants is one that she learned from William Robinson, an English landscape gardener whom she met on her grand tour of foreign gardens. Farrand believed that gardens should fit into the existing landscape, thus at Bellefield, she designed her garden to incorporate two existing trees, an oak and a hemlock (the hemlock has since been replaced). Furthermore, flowerbeds line the outer rim of the garden. While this is a pretty basic landscaping technique today, it was innovative in the early twentieth century. The color and texture of these beds were incredibly important to Farrand, who viewed their design as an artist would a painting. Farrand’s original plans for the garden encompassed a more formal garden inside a “wild” one, another key feature of her design style. She often mixed more formal garden layouts, such as those popular in Europe in this era, with more natural-looking landscapes and plant species.[8] Finished in 1912, this garden was enjoyed by the Newbold and then Morgan families for many years.

NPS Photo

NPS Photo

NPS Photo

UC Berkeley Environmental Design Archives

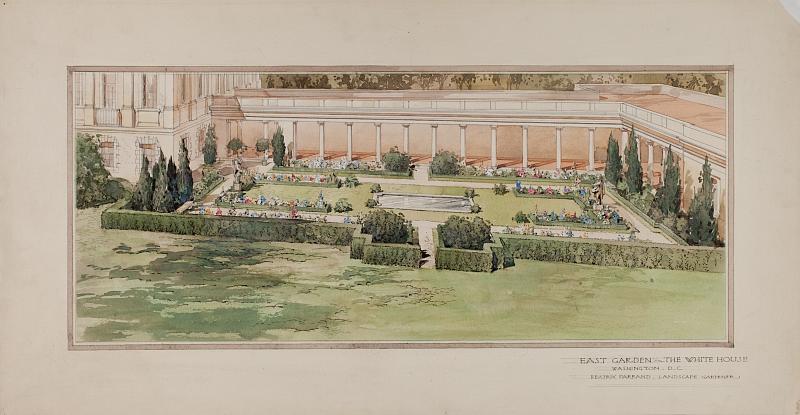

UC Berkeley Environmental Design Archives

UC Berkeley Environmental Design Archives

As Farrand’s career went on, she continued to design gardens for the private homes of the wealthy, as well as for college campuses. She became Princeton University’s first Consulting Landscape Gardener in 1912. It was here at Princeton that she met her husband, Max Farrand, a professor of history at Yale University. After they got married, Beatrix moved to New Haven, and worked as a Consulting Landscape Gardener at Yale from 1923-1945.[9] Farrand’s gardens at both Princeton and Yale included space-saving techniques, like vertical gardening and climbing plants. Her plant selections, always intentional, were notably so in the gardens she designed for Yale and Princeton. She chose plants that would look their best when classes were in session and highlighted the architecture of the campus. However, designing for these schools was not always a smooth process. She received pushback at both universities from male architects who sometimes did not agree with her methods or designs. The grounds staff at Princeton even referred to her as “the bush woman”, mocking her for her attention to detail. Despite pushback and mockery, she was able to come up with some beautiful designs, including the Wyman Garden at Princeton and 16 different landscapes at Yale. [10]

UC Berkeley Environmental Design Archives

UC Berkeley Environmental Design Archives

UC Berkeley Environmental Design Archives

Along with the garden at Bellefield and her work at Princeton and Yale, other notable commissions of Farrand’s career include the Rose Garden at New York Botanical Garden in New York City, two gardens at the White House, landscapes at Cal Tech and Occidental College, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden on Mount Desert Island in Maine, and the garden at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington D.C. The latter is considered her finest work. Furthermore, she helped to design eighty-two miles of roads and footpaths in Acadia National Park, as well as the landscapes surrounding them.[11] Additionally, Farrand established a landscape study center at her family home at Reef Point on Mount Desert Island, Maine, in hopes of educating people on horticulture and garden design, though it closed in 1955 after only a few years due to financial hardship.[12] Beatrix Farrand died on February 28, 1959 at age 86 on Mount Desert Island, after designing over 200 gardens during her prolific career.

Of landscape gardening, Farrand once said: “It is work, it is hard work, but at the same time it is perpetual pleasure... it seems to me all the arts are combined in this”[13] In doing this work that she found so enjoyable, Beatrix Farrand revolutionized the field of landscape architecture and gardening. Her oft used technique of mixing formal with “wild” elements in her gardens was incredibly innovative and original at a time when most garden designers were creating “facsimile gardens”, mere copies of gardens in European styles.[14] Furthermore, she was a trailblazer for women in landscape architecture, persisting even when her male counterparts did not take her seriously. Born into privilege, Beatrix Farrand defied the conventions of her class to make a career of creating beautiful landscapes, and in doing so, helped to open a new profession to women. We are happy to highlight her achievements for Women’s History Month.

Yale University

Yale University

Many of the gardens Beatrix Farrand designed for private residences have been removed over the years, but we are fortunate to have a surviving example at the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site. This garden fell into disrepair after the National Park Service acquired the Bellefield estate in the 1970s. But a group of volunteers worked with the NPS in 1993 to restore the garden to its former glory, using historic photographs and planting schemes from other Farrand gardens of that era (original planting plans for the Bellefield garden no longer exist).[15] The Beatrix Farrand garden at Bellefield is maintained by the Beatrix Farrand Garden Association and the NPS. It is open to the public everyday but Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day.

For more information on the Farrand Garden at Bellefield, including current planting plans, please visit the website of the Beatrix Farrand Garden Association.

Beatrix Farrand Garden Association

Beatrix Farrand Garden Association

Beatrix Farrand Garden Association

NPS Photo

NPS Photo

[1] Steven Ives, dir., Beatrix Farrand's American Landscapes (Insignia Films, 2019).

[2] "Beatrix Farrand", Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame, accessed February 2021, https://www.cwhf.org/inductees/beatrix-farrand.

[3] Steven Ives, dir., Beatrix Farrand's American Landscapes (Insignia Films, 2019).

[4] Ibid.

[5] "Beatrix Farrand", Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. accessed February 2021, https://www.cwhf.org/inductees/beatrix-farrand. , Steven Ives, dir., Beatrix Farrand's American Landscapes (Insignia Films, 2019). "Beatrix Farrand", National Park Service, accessed February 2021, https://www.nps.gov/people/beatrix-farrand.htm.

[6] Steven Ives, dir., Beatrix Farrand's American Landscapes (Insignia Films, 2019).

[7] "Beatrix Farrand", National Park Service, accessed February 2021, https://www.nps.gov/people/beatrix-farrand.htm.

[8] Steven Ives, dir., Beatrix Farrand's American Landscapes (Insignia Films, 2019)., "Walled Garden at Bellefield", National Park Service, accessed February 2021, https://www.nps.gov/places/walled-garden-at-bellefield.htm.[9] "Beatrix Farrand", Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. accessed February 2021, https://www.cwhf.org/inductees/beatrix-farrand.

[10] "Beatrix Farrand", Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. accessed February 2021, https://www.cwhf.org/inductees/beatrix-farrand. , Steven Ives, dir., Beatrix Farrand's American Landscapes (Insignia Films, 2019). "Beatrix Farrand", National Park Service, accessed February 2021, https://www.nps.gov/people/beatrix-farrand.htm. "Farrand Courtyard", Yale University, Accessed February 2021, https://visitorcenter.yale.edu/tours/women-yale/farrand-courtyard.

[11] Steven Ives, dir., Beatrix Farrand's American Landscapes (Insignia Films, 2019).

[12] "Beatrix Farrand", National Park Service, accessed February 2021, https://www.nps.gov/people/beatrix-farrand.htm.

[13] Steven Ives, dir., Beatrix Farrand's American Landscapes (Insignia Films, 2019).

[14] Ibid

[15] "Walled Garden at Bellefield", National Park Service, accessed February 2021, https://www.nps.gov/places/walled-garden-at-bellefield.htm