Tehran Conference

FDR and General Dwight D. Eisenhower (fdrfoundation.org)

The President was returning from the Tehran Conference in December of 1943 when he selected General Dwight D. Eisenhower to be the overall commander for OVERLORD (the D-Day invasion of France). It was also on this trip that Prime Minister Winston Churchill became quite sick and was temporarily unable to complete his journey home to England. It seemed FDR had been able to avoid the illness that befell his friend. But then on Christmas Day 1943, the President complained of feeling unwell. He exhibited a persistent cough and fatigue. During the early months of 1944 the President had good days and bad days. But as February led into March, the president’s declining health could no longer be ignored.

His Secretary Takes Notice

FDR and his secretary, Grace Tully (New York Times)

FDR and his secretary, Grace Tully (New York Times)In late February 1943, FDR’s secretary Grace Tully noted that the President seemed unusually tired, even in the morning, and that the circles under his eyes grew darker and his hands shook more than usual. He would even nod off occasionally while reading his mail or while dictating a letter. Tully was not alone in her observations.

His Daughter Steps In

FDR and his daughter, Anna (AP/George Skadding)

FDR and his daughter, Anna (AP/George Skadding)The President’s daughter Anna had noticed a decline in her father’s health over the winter of 1943 into early spring 1944. During the last week of March, the President’s temperature reached 104 degrees and he took to his bed. Anna confronted Admiral Ross McIntire, the President’s White House physician. McIntire responded that FDR was simply having a bout of seasonal flu. Anna was not persuaded and pushed for more to be done. McIntire understood that Anna was not going to give in, and he made arrangements for FDR to have a full checkup at the Bethesda Naval Hospital.

Bethesda Naval Hospital (National Archives)

Admiral Dr. Ross McIntire (National Archives)

The Specialist Takes Over

Lt. Commander, Dr. Howard Bruenn (Navy Live Medicine)

On March 27th, 1944, as the President was getting into his car, White House aide William Hassett asked FDR how he felt. FDR said, “I feel like hell!” On arrival at the hospital FDR was met by Lt. Commander Dr. Howard Bruenn of the Naval reserve, a cardiologist from Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in New York. Bruenn was shocked by the President’s appearance, he noted, “I suspected something was terribly wrong as soon as I looked at the President, his face was pallid and there was a bluish discoloration of his skin, lips and nail beds… the bluish tint meant the tissues were not being supplied with adequate oxygen.” The doctor noted that FDR was having difficulty breathing with any exertion and listened to his heart with a stethoscope. “It was worse than I feared,” the doctor recalled. X-rays and an electrocardiogram revealed cardiomegaly (an enlargement of the heart muscle), congestive heart failure, and a heart murmur (mitral valve not closing properly). The President’s blood pressure (which mysteriously hadn’t been checked since February 27, 1941) was measured at 186/108. Though this blood pressure today would be considered cause for concern, that was not the case at the time. Rising blood pressure as one aged was considered normal. As time went on, however, the President’s blood pressure would become much more worrisome and would eventually rise to 260/150. FDR’s health was becoming a “ticking timebomb.”

Consultation

Dr. Jame Paullin (American Medical Association)

Dr. Frank Lahey (Lahey.org)

Dr. Bruenn battled with his superior, Admiral McIntire, about the course of treatment for FDR moving forward and consulted with two well-known doctors, Dr. James Paullin of Atlanta, who held the position of President of the American Medical Association, and Dr. Frank Lahey of Boston, founder of the Lahey Clinic in Boston. Decisions were made to reduce the number of hours the President worked each day, reduce his weight to ease the burden on the heart, cut his cigarettes down to 10 a day, and reduce, but not eliminate, the number of cocktails he had in the evening. The most impactful change was treating the President with digitalis. This treatment allowed the heart to beat more efficiently and led to a reduction in the size of his heart and improved the President’s breathing upon exertion. There is no evidence that FDR was included in the discussions regarding his treatment, though he seemed to take his doctors’ advice to heart. His condition improved for a time. The press and the American people were kept in the dark on all of this. Even the president himself may not have known how sick he really was.

Bremerton Speech

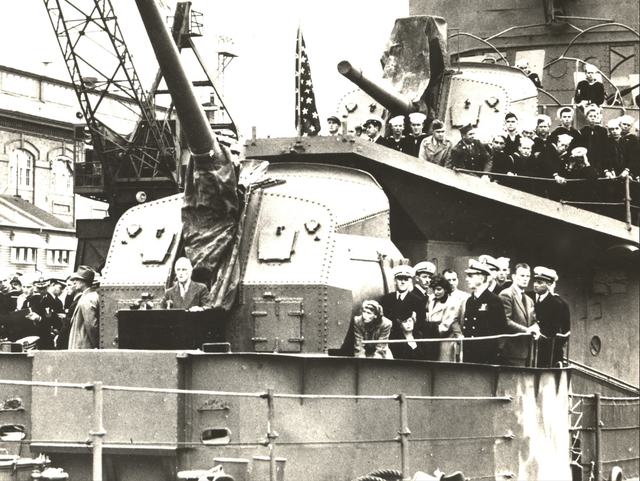

FDR speaks at Bremerton Navy Yard as Anna Roosevelt looks on, concerned (Library of Congress)

FDR speaks at Bremerton Navy Yard as Anna Roosevelt looks on, concerned (Library of Congress)The American public would get their first hint of FDR’s failing health during a radio broadcast that the President gave from the deck of a destroyer in the Bremerton, Washington Shipyard. The President decided to stand up for his speech. He had not worn his leg braces for several months, and he had lost almost 20 pounds. His leg braces no longer fit properly and painfully dug into his flanks. There was a stiff breeze which caused the ship to rock, making it very difficult for FDR to hold on to the podium and his notes at the same time. It came off in a halting, rambling way as he talked about his recent travels to military bases around the pacific. Sam Rosenman (one of FDR’s speech writers) even said, “it looks like the old master has lost his touch.” At about ten minutes into his talk, FDR began to have severe chest pain radiating into both shoulders. He somehow got through the speech. Immediately afterwards he confessed this episode to Dr. Bruenn who had been waiting below decks. The doctor gave the President an electrocardiogram immediately, and to his relief saw that it was a transient event and caused no permanent damage to FDR’s heart. (Note the President’s daughter Anna looking on from the right with a look of concern in the photo above.)

OCTAGON Conference

Octagon Conference. Front row: Mackenzie King, FDR, Churchill. Back row: the Combined Chiefs of Staff. (National Archives)

Octagon Conference. Front row: Mackenzie King, FDR, Churchill. Back row: the Combined Chiefs of Staff. (National Archives)FDR was back in Washington, D.C. by August 15th, 1944 but was off to the OCTAGON Conference with Churchill in Quebec the following month. During this conference, a concerned Churchill sought out Dr. McIntire to inquire about the President’s appearance. The Prime Minister was justly concerned, but McIntire assured him that the President was fine. “With all my heart I hope so,” Churchill replied. “We cannot have anything happen to that man.

Running for the Fourth Term

Thomas Dewey, FDR's Republican opponent in the Presidential Election of 1944 (Truman Presidential Library)

FDR pulled himself together for the campaign of 1944. This campaign, being war-time, wasn’t in any way typical. Because of the demands of the war, which was finally turning in the Allies' favor, FDR did not start campaigning until late September. His first real campaign event was on September 23 when he gave a speech at a dinner for the Teamsters Union in Washington, D.C. It was a remarkable piece of political showmanship and immediately changed the dynamic of the contest. The Dewey campaign had been attacking the Roosevelt administration as corrupt and incompetent and had accused FDR of sending a U.S. Navy destroyer to pick up his Scottish Terrier Fala after he had been accidentally left behind during the President’s visit to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. An exerpt of that speech is as follows:

“These Republican leaders have not been content with attacks on me, or my wife, or on my sons. No, not content with that, they now include my little dog, Fala. Well, of course, I don’t resent attacks, and my family doesn’t resent attacks, but Fala does resent them. You know, Fala is Scotch, and being a Scottie, as soon as he learned that the Republican fiction writers in Congress and out had concocted a story that I’d left him behind on an Aleutian island and had sent a destroyer back to find him—at a cost to the taxpayers of two or three, or eight or twenty million dollars—his Scotch soul was furious. He has not been the same dog since. I am accustomed to hearing malicious falsehoods about myself … But I think I have a right to resent, to object, to libelous statements about my dog.”

FDR and Fala at the FDR Memorial in Washington D.C. (NPS)

Campaigning in the Rain

FDR campaigning in 1944 (Library of Congress)

The remaining question still lingering before the election of 1944 was one of the President’s health. But FDR was determined to prove he was fit for the job. On October 21st, 1944, the President went about demonstrating that he was. He undertook a four-hour tour of New York City in an open car in the pouring rain. He was soaked immediately. He toured four of the five boroughs of New York City. Three million New Yorkers came out to see him, despite the poor weather. That evening he managed to deliver an international policy address at the Waldorf-Astoria to the Foreign Policy Association. He repeated this performance in Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston. Any questions the opposition had about the President’s health were vanquished.

He Still Has It

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, seated in his study, 1944 (National Archives)

When the campaign of 1944 ended, the President was given a checkup by his cardiologist, Dr. Bruenn, who by now travelled with FDR wherever he went. Dr. Bruenn was impressed by how well FDR had come through the grueling campaign. The doctor noted, “[he] really enjoyed the hustings and his Blood Pressure levels, if anything were lower than before. He is eating better, and despite prolonged periods of exposure, he has not contracted any upper respiratory infections. The patient seems to be well stabilized on his digitalis regime.”

He Wins Again

Newspaper announcing FDR’s election to a fourth term (Library of Congress)

Roosevelt defeated Dewey by a good margin, 432 electoral votes to 99. But just after the election the President’s health resumed its decline. His appetite faded and he lost more weight. His blood pressure was reaching new highs, climbing to 260/150. His regular electrocardiograms continued with no sign of trouble and no evidence of digitalis toxicity. On January 19th, 1945, after a two-hour cabinet meeting, his Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins noted the President’s fatigue: “He looked like an invalid who had been allowed to see guests for the first time and the guests had stayed too long.”

Yalta Conference

Winston Churchill, FDR, and Joseph Stalin at the Yalta Conference (U. S. Signal Corp, via The New York Times)

Winston Churchill, FDR, and Joseph Stalin at the Yalta Conference (U. S. Signal Corp, via The New York Times)Two days after the inauguration, FDR left for the Yalta Conference, which would convene on February 4th, 1945, only five days after FDR’s 63rd birthday. Photos taken at Yalta show the President looking 20 years older than he was. FDR would have to endure long hours at the conference followed by long hours of dinner and toasts with cocktails in the evening. Churchill and Stalin both privately expressed concern for the President. On the other hand, members of the American delegation saw things differently. Secretary of State Edward Stettinius thought FDR appeared “cheerful, calm and quite rested.” Just as with the Tehran Conference, it was determined that FDR would preside over the meetings. Admiral Leahy felt that the President handled himself very well. “His personality dominated the discussions. He looked fatigued when he left, but so did we all.” Charles Bolen of the U.S. State department and FDR’s translator throughout the conference said, “While his physical state was not up to normal, his mental and psychological state was certainly not affected. Our leader was ill, but he was effective.” Dr. Bruenn remarked to the President’s daughter Anna, who had accompanied her father on the journey, "[FDR] had a serious ticker situation” but was not overly concerned.

He Reveals His Disability

FDR speaking before a Joint Session of Congress on March 1st, 1945 (FDR Presidential Library)

FDR speaking before a Joint Session of Congress on March 1st, 1945 (FDR Presidential Library)Upon return to the United States the President would make his report to the American people. In this case that would come on March 1st, 1945 before a joint session of Congress. The President made his appearance by being wheeled down the aisle in his wheelchair. Frances Perkins recalled, “It was the first reference he had ever made to his incapacity. He did it with such a casual, debonair manner, without self-pity or strain that the episode lost any grim quality and left everyone quite comfortable. His face was gay, his eyes were bright, his skin was a good color again. His speech was good. His delivery and appearance were those of a man in good health.” The President spoke for almost an hour. His message was clear: “I hope that you will pardon me for this unusual posture of sitting down during the presentation of what I want to say, but I know that you will realize that it makes it a lot easier for me not to have to carry about ten pounds of steel around on the bottom of my legs; and also because of the fact that I have just completed a fourteen-thousand-mile trip. First of all, I want to say, it is good to be home.” He then gave a detailed summary of the plans for bringing the war to a close. He later continued, “The Crimea Conference was a successful effort by the three leading Nations to find a common ground for peace. It ought to spell the end of the system of unilateral action, the exclusive alliances, the spheres of influence, the balances of power, and all the other expedients that have been tried for centuries and always failed… This time, as we fight together to win the war finally, we work together to keep it from happening again.” His real vision and his hope for mankind were expressed with these words:

“The structure of world peace cannot be the work of one man, or one party, or one Nation. It cannot be just an American peace, or a British peace, or a Russian, a French, or a Chinese peace. It cannot be a peace of large Nations or of small Nations. It must be a peace which rests on the cooperative effort of the whole world. It cannot be a structure of complete perfection at first. But it can be a peace—and it will be a peace—based on the sound and just principles of the Atlantic Charter—on the concept of the dignity of the human being—and on the guarantees of tolerance and freedom of religious worship.”

Exhausted

FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt seated together in an automobile (Brooklyn Public Library)

The campaign of 1944, the grueling trip to and from the Crimea, and his tenuous health had left the President exhausted. On Saint Patrick’s Day, the President and First Lady celebrated their fortieth wedding anniversary. By this time Dr. Bruenn had noted that the President was working too hard, seeing too many people and working too late into the evenings. “His appetite had become poor, it appeared that he was losing weight. He complained of not being able to taste his food.”

“All that is within me cries out to go back to my home on the Hudson River”

Springwood, the home of FDR (NPS)

Living Room at Springwood (NPS)

The President left for a brief rest in Hyde Park on March 24th, 1945. Eleanor noticed that for the first time FDR did not want to drive himself. He let her drive, and he let her mix the drinks before dinner. His tenuous grip on life was slipping away.

Time to See an Old Friend

FDR's Little White House in Warm Springs, Georiga (NPS)

FDR arrived in Warm Spring Georgia on March 30th, 1945 for some desperately needed rest and relaxation. He drove himself from the train station to the Little White House with his cousins Daisy Suckley and Laura Delano. The weather was perfect, and FDR seemed to improve immediately. Dr. Bruenn noted, “Within a week there was a decided and obvious improvement in his appearance and sense of well-being. He had begun to eat with appetite, rested beautifully and was in excellent spirits. He began to go out every afternoon for short motor trips, which he clearly enjoyed. The physical exam was unchanged except for the blood pressure, the level of which had become extremely wide-ranging from 170/88 to 240/130.”

A Little Rest

Lucy Mercer Rutherford (NPS)

On Monday April 9th, Lucy Mercer Rutherford arrived with her friend, artist Elizabeth Shoumatoff, who had come along to paint a portrait of the President. Shoumatoff reported that the President was full of jokes and the dinner conversation ranged from Churchill to Stalin to food.

He’s Slipping Away

FDR and Henry Morgenthau Jr., his Treasury Secretary (FDR Presidential Library)

FDR and Henry Morgenthau Jr., his Treasury Secretary (FDR Presidential Library)On April 11th, FDR was working on his Jefferson Day speech while the artist worked on his portrait. FDR wrote, “The only limit to our realization of tomorrow will be our doubts of today. Let us move forward with strong and active faith.” That evening during dinner Henry Morgenthau recalled, “I found he had aged terrifically and looked very haggard. His hands shook so that he started knocking over the glasses. I had to hold each glass as he poured out the cocktail… I found his memory bad and he was constantly confusing names. I have never seen him have so much difficulty transferring himself from his wheelchair to a regular chair, and I was in agony watching him.”

Eternal Rest

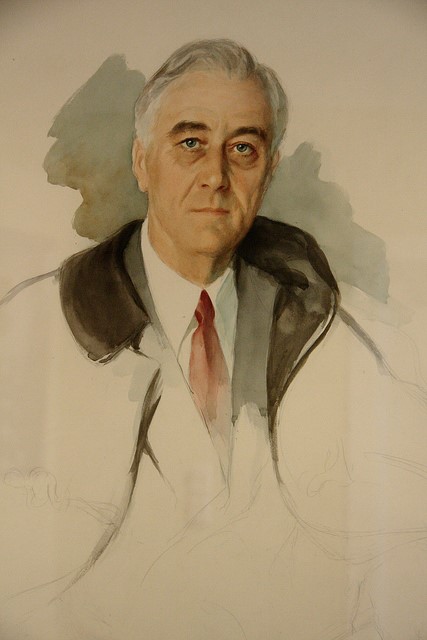

“The Unfinished Portrait” by Elizabeth Shoumatoff" (Photo of painting courtesy of Library of Congress)

The next day, April 12th, 1945 the President was sitting for his portrait while Shoumatoff painted. She thought he was looking much better, the gray pallor was gone, and he had “exceptionally good color.” She would later learn from his doctor that this was likely a warning sign of an impending cerebral hemorrhage. Just before 1 pm, as the butler was setting the table for lunch, the President said, “We have fifteen minutes more to work,’ then in a sudden motion he raised his hand to his head and said, “I have a terrific pain in the back of my head.” The President slumped forward in his chair and collapsed. He would never regain consciousness. Staff immediately left to get Dr. Bruenn. The President was moved to his bed and at 3:55 pm on April 12th, 1945, he was pronounced dead. Three days later, on April 15th, 1945, the President’s body was laid to rest in his mother’s rose garden in front of his lifelong home in Hyde Park, New York. The world mourned. From world leaders to the average citizen, people eulogized the President. Republican Senator Robert Taft, who long opposed FDR and his policies, had this to say: “The President’s death removed the greatest figure of our time at the very climax of his career, and shocks the world to which his words and actions were more important than that of any other man. He dies a hero of the war, for he literally worked himself to death in the service of the American people.”

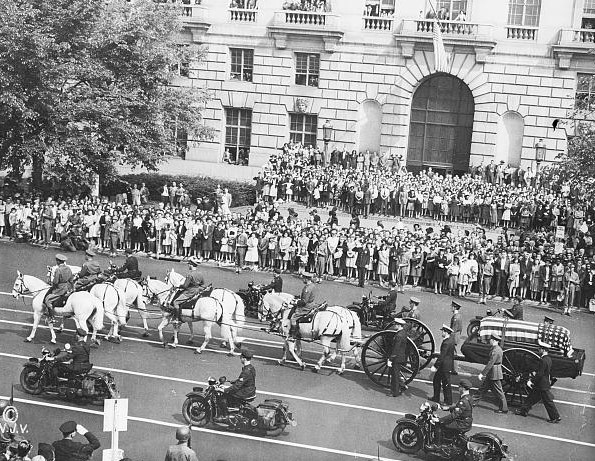

FDR's Funeral Procession (Library of Congress)

FDR's Funeral Procession (Library of Congress)

Churchill with Eleanor Roosevelt at FDR’s grave in March 1946 (Library of Congress)

The Roosevelts’ Gravesite with Colorguard of several West Point Cadets (NPS)

The Roosevelts’ Gravesite with Colorguard of several West Point Cadets (NPS)