Obvious similarities between the phonautograph and the phonograph raise the questions: Did Edison set out to improve upon Scott's phonautograph? Was he explicitly building on this existing technology, or did he come to the idea of sound recording independently? Primary sources are silent on whether Edison even knew of the phonautograph in 1877. Had he run across accounts of the phonautograph in scientific literature, evidence suggests he would have concurred with the scientific community’s underestimation of its recording fidelity. He wrote as much in a marginal comment in his copy of German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz’s book On the Sensations of Tone: “Untrue Record—this instrument never gives true record[ing].” (Partially erased, this could have been written before or after the invention of the phonograph.)

National Park Service (EDIS 225532)

The following documents sketch Edison’s indirect path to the phonograph. Had he been working to improve the phonautograph rather than the telephone, he would certainly have travelled a much different path. JULY—Edison conceives of the phonograph. At the bottom of a page of ideas for the telephone (“speaking telegraph”, below left) Edison scribbled his idea that telephonic signals (voices) could be recorded and reproduced in the same way as telegraphic signals (dots and dashes) for the same practical reasons: to time-shift incoming messages, speed them up for efficient retransmission, and slow them down for accurate transcription: Just tried experiment with a diaphragm having an embossing point and held against paraffin paper moving rapidly. The speaking vibrations are indented nicely and there’s no doubt that I shall be able to store up and reproduce automatically at any future time the human voice perfectly reproduced slow or fast by a copyist and written down…. Sheet after received is sent to copyist who’ll pass it in machine similar to that shewn on other page and copied at rate of 25 words per minute whereas it was sent at rate of 100 per minute…

National Park Service These two pages (above) were separated more than a century ago. Indeed, the first page exists only in facsimile. Note how the dates differ–a result of Edison and his associates gathering loose sheets from the lab and signing them in batches. Only in 2007 did researcher Patrick Feaster realize the two pages went together. In this way, ready online access to The Thomas A. Edison Papers at Rutgers University allows us to more accurately track Edison’s inventive process.

Scientific American When making different sized telephone diaphragms it was a very common usage to mount them in a frame with a mouthpiece, hold them up, and talk to them in a loud or low voice; at the same time putting a finger close to the centre to feel how much vibration was communicated to them.

One night, after supper (which was prepared for us at midnight) and at which all the principal workers sat down together; Mr. Edison who had been trying different diaphragms in this manner suddenly remarked "Do you know Batch I believe if we put a point on the centre of that diaphragm and talked to it whilst we pulled some of that waxed paper under it so that it could indent it, It would give us back talking when we pulled the paper through the second time’—The brilliancy of the suggestion did not at first strike any of us—It was so obvious that it would do so that everyone said `Why of course it must!!’ I said We’ll try it mighty quick! and we went to work—Mr. Kruesi the Chief Mechanician took the diaphragm to solder on to it at the middle a needle point about ¼” long; he also took one of the automatic telegraph wheels and stands to fasten the diaphragm to so that we could draw the paper through easily— I cut and got ready some strips of paper of different thicknesses of parafin coating— It was a matter of an hour or so when we all got together again to make a trial— We fixed the instrument on to a table and I put in a strip of paper and adjusted the needle point down until it just pressed lightly on the paper— Mr. Edison sat down and putting his mouth to the mouthpiece delivered one of our favorite stereotyped sentences used in experimenting on the telephone "Mary had a little lamb" whilst I pulled the paper through— We looked at the strip and noticed the irregular marks, then we put it in again and I pulled it through as nearly at the same speed as I had pulled it in the first place and we got "ary ad elll am" something that was not fine talking, but the shape of it was there, and so like the talking that we all let out a yell of satisfaction and a "Golly it’s there"!! and shook hands all round— We tried it many times and in many different ways continually improving the apparatus during the early morning— During the time that some of these changes were being made Edison & I would talk about the possibilities of such an invention and it was then that we fully realized the brilliancy of the suggestion and the magnitude of its possible applications—Before breakfast the next morning we had reproduced almost perfect articulation from a strip of the waxed paper which I had embossed as it were with a ridge in the middle running the whole length, the needle point in this case was ground chisel shaped. [Transcribed from: Charles Batchelor Journal, November 4, 1905 to June 19, 1908, NPS catalog # EDIS 1339.]

National Park Service [Document reference: NV17015.]

National Park Service [Document reference: NS7703D.]

National Park Service [Document reference: NV17022.]

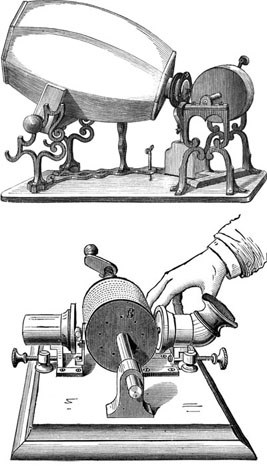

Edison’s Embossing Translating Telegraph made evident the many advantages of recording messages on a flat surface: Unlike foil wrapped around a mandrel, the flat record could be taken off the turntable and later put back on; it could be filed away in a folder for later use; and it held the greatest promise for making copies. In 1877 and 1878 plate (later called “disc”) designs appeared in laboratory sketches and patent applications nearly as much as cylinder designs. From lab records and published accounts we know that Edison had a plate phonograph built early in 1878. It was driven by a spring motor to help maintain a constant speed during recording and playback. Although Edison called it his “improved phonograph”, accounts suggest that it worked better in theory than in practice. In order to meet commercial demands for reliable phonographs, Edison’s shop designed simpler hand-cranked cylinder machines with large flywheels instead of motors. Simplicity has its virtues.

This exhibit continues here: Charles Cros: The Paléophone Process Go back to Thomas Edison: The Phonograph [ Return to Who Invented Sound Recording? ] [ Return to The Origins of Sound Recording opening page. ] ——————————

|

Last updated: July 17, 2017