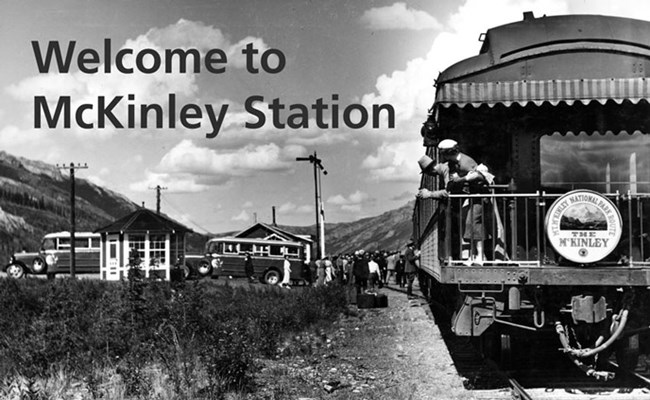

Photo Courtesy of P44-05-074 Alaska State Library, Skinner Foundation Photograph Collection The McKinley Station Trail is a moderate walk of 1.6 miles (2.6 km), one hour one-way, from the Denali Visitor Center to the Riley Creek Campground or Riley Creek Mercantile, with 100 feet of elevation change, up to 8.5 percent grade, on a 48-inch compacted gravel surface. It forms a 3.0-mile (4.8 km) loop with the Bike Path. Highlights include historic building remains, geologic features, the railroad trestle, and Riley Creek.

Much of the material presented here first is found in, or adapted from, the book, McKinley Station: People of the Pioneer Park, by Tom Walker, Pictorial Histories Publishing, Missoula, Montana, 2009

Park Road and Early Entrance: Until 1932, the boundary of Mount McKinley National Park lay a few miles to the west of here. Upon its completion in 1938, the Park Road led 92 miles from the railroad depot to the Kantishna Mining District, just outside the park boundary at that time. Much of the road was cut by hand by teams of laborers, at a finished cost of around $1.3 million. In the days before lightweight chainsaws and powerful earthmovers, the road project rang with the sound of axes and handsaws, the clang of shovel and pick, the clop of horses, and the sputtering of under-powered machinery.

Mount McKinley Park Hotel: Maurice Morino's hotel opened for business on Thanksgiving Day 1921. For almost two decades, people from far and wide gathered at this rustic hotel to celebrate holidays, hold dances and socials, and to enliven the long winter nights. Here, dog mushers and trappers mingled with miners and rangers, schoolteachers and itinerants, and once, a U.S. president.

Residents of the Station: The trail here follows one of the original railroad construction access roads that led up out of Riley Creek to the bluff above. The route winds steadily downhill but briefly flattens out on a few small plateaus. In separate arrangements with Maurice Morino, whose land the trail traversed, people built cabins on these plateaus, trading labor for free rent. Residents at the time included Woodbury Abbey who came to conduct the park's first boundary survey; schoolteacher Mrs. Louise Ann Fairburn; miner Elmer Hosler and his wife, Maud, the postmaster.

Who Were Riley and Hines? You are now standing on the south bank of Hines Creek. In the 1920s, your view would have been of a wide, treeless and rocky flat, with two streams-Hines and Riley-converging nearby. Both streams were important to pioneer residents. Riley Creek provided access to the mountains for hunters and wood gatherers; a trail on Hines Creek led west toward the park. One enduring mystery is the identity of the people for whom these creeks were named.

Original Park Headquarters: The park's first ranger, Harry Karstens, arrived in early summer 1921, and began the pioneering work of establishing the rule of law in the new park. After a summer of meeting people and a long patrol through the park, Karstens began clearing land for his headquarters on the northwest bank of Riley Creek, upstream from the bridge. It offered an ideal place to monitor people using the trail leading to the park.

Alaska Railroad Trestle: The steel bridge looming high above looks much the same as it did upon its completion in early 1922, with one exception. Gone is the football-field-length wooden trestle that originally connected the steel structure to the north bluff. In the 1950s, the railroad hauled hundreds of tons of rock and earth to extend the bluff to the edge of the first concrete and steel support. Except for a change of the vegetation, the view of the bridge to the south is unchanged.

The Hole: You are now standing at the northwest corner of Maurice Morino's original roadhouse, built in a wide clearing overlooking the creek. Imagine the isolation here when Morino built his cabin in 1914: No road, no railroad, no easy overland trail, and the Nenana River unfit for navigation due to its thunderous rapids and steep-walled gorge. This area, below the bridge and at the junction of two trails, eventually became known as "the hole," an area off limits to the station's children. The illicit traits of the "Roaring 20s"-bootlegging, alcohol manufacturing, gambling, violence, and prostitution - were centered here.

Mount McKinley Silver Fox Ranch: Until the late 1920s, raising captive foxes for their fur, called "fox farming," was a burgeoning industry. The cold, long winters that characterized the Riley Creek bottomland offered near ideal conditions for breeding foxes with luxurious fur. Silver foxes, an almost black color phase of red fox, were especially valuable and in high demand both in the U.S. and abroad. The spot where you stand now is the former site of Duke and Elizabeth Stubbs' Mount McKinley Silver Fox Ranch, a business that sold furs both to tourists and fur buyers, and supplied breeding pairs of foxes to fur farms across Alaska.

Welcome to the McKinley Station Trail!

End of an Era ...... and the walking tour. Conservationists hailed the extension as a long overdue move to protect the eastern boundary of the park. Park regulations held sway over the surrounding land. Sheep and caribou herds that lived on the hills overlooking the river would now be protected. Local residents viewed the changes with dismay. With the expansion, McKinley Station as a viable community came to an end and its citizens scattered, some moved north to Healy, others south to Cantwell. In the wake of its passing, left behind today in cabin berms and debris piles, are remnants of the hopes, dreams, and lives of the people who once called McKinley Station home. |

Last updated: July 29, 2021