Alan ChanBased in Los Angeles, CA, Alan Chan often takes inspiration from his cross-cultural experience as a resident in America, East Asia and Europe, and from visual arts and poetry. He founded the Alan Chan Jazz Orchestra in 2011 to explore a wide range of musical possibilities with his original works. Its debut album "Shrimp Tale" (2014) received raved reviews and radio plays across the U.S and abroad. In 2012, he created an ambitious one-hour piece for his jazz septet in New York City titled "Winter News," after John Haines' inspirational poetry collection. Alan Chan is the winner of the 2015 ASCAP/SJO "George Duke" Commissioning Prize, and he is composing a new work for the 67-piece Symphonic Jazz Orchestra for their 2016/17 season. His genre-shaking music has been recognized with awards and fellowships from ArtEZ (Netherlands), New Music USA, Percussive Arts Society and Los Angeles County Arts Commission, among others. Visit Alan Chan's website. Jessica GoodfellowIntroduction My mother’s only sibling, Steve Taylor, was one of seven climbers lost on Denali in the 1967 Wilcox Expedition. These poems deal with the dichotomy between the savage beauty of the park (including the incredible nine days that Denali was visible during my visit) and the tragic family history that drew me t/here. I cannot thank the park staff enough for bringing me here, and for helping make my stay meaningful. I follow the road my uncle followed

forty-nine years ago. One way. All day drizzle and dust smear my wind- shield. Sepia creeps from the edges inward. A bull moose, solitary on the roadside, with upturned antlers rakes the rain. Dall sheep stipple a deeply purpled shelf, far constellation deep in escape terrain. Clouds crowd Polychrome Pass, the colors of Monet’s Haystacks on a Foggy Morning. Divide Mountain’s outcrops—as long-faced and open-mouthed as organ pipes—gape. Ten o’clock at night. The clouds snag on the backs of ragged mountains and unravel. Above the cabin, the sun swings a wide arc. The sky is suddenly brighter, bluer than ice. Sleepless. Everywhere I wander is at center in the sun’s lasso. Day’s end, and our bodies do not believe it is the end. Beyond the caribou tracks, the river braids itself

over gravel bars. The rocks that parse the river also braid themselves with color—gray, ochre, black. Some are simply banded by a white stripe into halves: before, and after. Others bear seams as tangled as lines on a map—a record of all the forces that have brought them here. Now. I look up, see Denali, a band of white through unbraiding clouds—all that has brought me here is riven in two: before the tragedy, and after. Around me the Toklat twines itself like the veins running blood and history through my wrists. Memory, like cold glacial melt, hauls more sediment than it can hold, churns, scatters what it forsakes, strands in splintered islands the truths on which we break. Mid-August and already the tall fireweed darkens into autumn. The mountainside is dotted with blueberries, soapberries, cranberries low to the ground. Beneath our lifting heels the spongy tundra springs back as if we were never here. Every day sunset comes six minutes sooner. On the ridge, the shadow of a golden eagle is visible before the eagle is. Up here there is nothing between me and Nothing. drags my

gaze around— a teeter-totter of blue and black a wink of stark white epaulet crazed-glass wings a sheen of green a swaggering wand of opal tail— then with a shake of lacquered beak and a fling of fingery wings is gone My sister’s drawn to clean-edged kettle ponds,

learning how to tell which pools were formed in basins left behind by glaciers, and which weren’t. I’m captivated by erratics, empty-house-sized boulders stranded in a strange land by ice that melted out from underneath them. Erratic comes from the Latin errare, meaning to wander, to stray, to err. We are not wrong, my sister and I, to feel kindred— kin and dread—with what remains after a mammoth force, no longer visible, has carved out such a tattered landscape. All stones are broken stones. ~James Richardson

Someone, or someones, have littered the window ledge with river rocks—gray, or black, each with a white stripe through the middle like a mirror. On the porch, too, someone has left an array of two-toned stones. Wandering the river bars, I look for an offering to the cabin I share with my unknown predecessors and their mineral obsessions. But each rock I lift from the river is returned, set back down—some now, some tomorrow. Northbound means bound for the north, while housebound means bound to the house. In this cabin, this northerly house, what is bound is—like the river rocks— of two contrasting origins, forged into one: this relentless beauty and my grandmother’s grief. cross fox under a three-quarter moon

crosses the road ahead of me, ground squirrel dangling from his jaws we who range the night, in quest of respite from our hungers, regard one another under the moon, not yet full An abacus of saxifrage,

wild celery’s geometry, but to what do you liken lichen? If bear flowers are a favorite of the bears, are windflowers winsome to the wind? Wooly lousewort or weasel snout— which name is worse for stalks of pastel bundled on the tundra? Black spruce leaning deep green atop paler green taiga—is it by supping on melted permafrost they get drunken? If soapberries are as bitter in the mouth as soap, what can the person who named cloudberries know of a mouthful of sky? Aven seed heads and cotton grass are like gauzy ghosts floating over the tundra— to what are you tethered? Fireweed, ubiquitous fireweed, the color of elusive alpenglow—so many words for warmth beneath North America’s icy crown. Hiking Past Thorofare Cabin

Through chest-high willow and alder, through thickets beaded with blueberries that dangle above fresh bear scat— we see The Great One, cloudless. Each step in the sodden tundra forces bubbles out of the mud— the earth is breathing with us as we push our way closer. The cabin is uninhabited—we look in as we pass, heading toward the moraine of the Muldrow Glacier and the river that is its meltwater. Soon it will be autumn. The brush will explode in golds, the fireweed in red. The grizzlies will finish their forage. We will not be here. The glacier will inch toward our absence. is a feral river, a skein of silt and gravel disheveled by rough waters. Impediment, irreverent are those who try to cross, thinks the river in its ever-changing mind, its slow kaleidoscope of sediment and melt. My uncle is one who crossed, baptized by clouds and polar waters. This is as close as I’ll get— on foot— to my uncle’s unmarked mountain grave. The river mothered by a glacier rushes between, buffering flesh from if, whether from weather— a storm is a cosmic accomplice. Denali in the distance is sleek, geometric, indifferent. The river’s flanked on that far side by breath- taking grandeur, on this side by a selvage of dark pines. Breathe the beauty in. Breathe the sorrow out. Pretend for a moment not to know: there are in these woods wolves—two competing packs— out of sight, and circling, circling. The mountains are alive. ~Clay Dillard, pilot

1. The mountain appears through a venetian blind of clouds—stripes of weather, granite, snow. 2. Mountain and sky the same indigoes and whites as The Blue Marble. Fast-moving clouds are too high to hide the peaks, but their shadows sweep across the ridges— the opposite of spotlights. 3. Thick clouds hide all but shifting glimpses of the mountain, mottled white and gray as the fifteen stones at Ryoanji’s zen garden, which from no angle can all be seen at once. 4. The clear blue slate of Wonder Lake twins the sky. Counting the reflection there are two Denalis. My uncle could be anywhere. 5. Fish-scale moon above Denali at midnight— iridescent, incandescent, partly darkled— a frozen fire and the spark that has escaped it. 6. Wind shuffles the clouds in a cosmic shell game while we wager: under which thunderhead does the summit lie. 7. The mountain’s north faces have ridges crisp as datelines— ash blue todays on one side, white nothings on the other. 8. The blank white pages of Denali, Foraker, and Hunter are smudged across their bottom margins by the inky scrawl of smaller ridges— scribbles of unreadable runes. 9. Behind us, the park road winds toward the mountain like a fuse. we drive a direction

my uncle never did, see vistas from slants he never will. From the brush four bears spill onto the road— three snuffling cubs and their mother. I wonder what to say to my mother about my visit to the park where her brother’s body lies. A covey of ptarmigan—eleven, twelve, fourteen—like nervous thoughts scatter, dart, convene. Should I tell how I hiked as near as I could to where he had been—Wonder Lake, the Muldrow Glacier moraine? Out the back window Denali is cloudier than it has been, and farther. And gone. Should I mention the magpies flashing their blue-black wings at Eielson, where she once waited, blue eyes dark with fear? Mile after mile, we scan the landscape for last signs of fox, moose, wolves, for anything that moves. When we speak of him, my mother answers questions until her face closes— “I’m finished talking for now.” Across the taiga a caribou has worried his antlers on trees till the velvet is torn, raw, cranberry-bright with blood. Soon, soon, he’ll shed his heady load. But not yet. Jessica Goodfellow, a Pennsylvania native currently residing in Japan, has published two books of poetry: Mendeleev’s Mandala (Mayapple Press, 2015) and The Insomniac’s Weather Report (Two Candles Press First Book Award, 2011; reprinted by Isobar Press, 2014). Her poetry chapbook A Pilgrim’s Guide to Chaos in the Heartland received the Concrete Wolf Chapbook Prize. Her publication credits include Best New Poets, Hunger Mountain, and Copper Nickel, among others. Recipient of the Chad Walsh Poetry Prize from the Beloit Poetry Journal, as well as the Linda Julian Essay Award and the Sue Lile Inman Fiction Prize, both from the Emrys Foundation, she’s had poems featured on NPR’s The Writer’s Almanac. Her work has been made into a short film by Motionpoems. Jessica has graduate degrees from the University of New England and Caltech, and imagery from science and mathematics plays a large role in her writing. Currently she is working on the poetry manuscript WHITEOUT, about her uncle’s death on Denali, along with six other climbers, during the Joe Wilcox expedition in 1967. She teaches at a women’s college in Kobe, Japan.

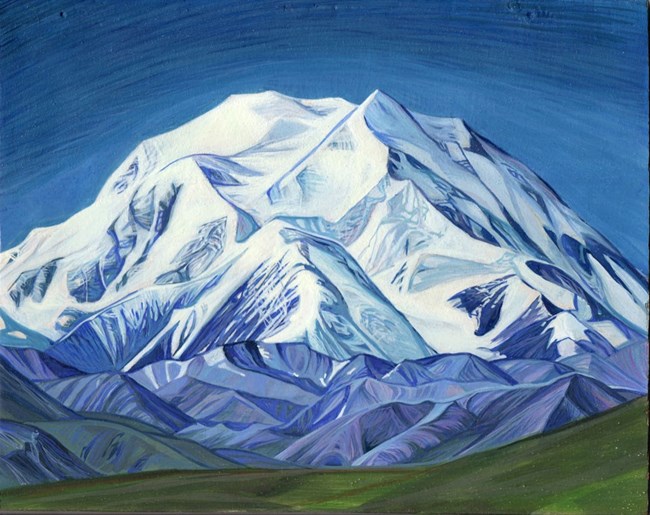

Kathy HodgeKathy Hodge was born in Providence, RI. As a teenager she took up her parents' oil paints, put aside after they graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design and started their family of seven children. Like her parents, she attended RISD and majored in painting, completing her BFA at the Swain School of Design in New Bedford, MA. She has been painting ever since, with a special attraction to the natural world and has felt extremely fortunate to have been appointed 12 times to serve as Artist in Residence in our national parks and forests. She has exhibited her work in many solo shows, most recently showing paintings from the Tongass and Chugach National Forests. Her involvement with the Artist in Residence Program has inspired her to start an Online Community for AIRs to meet and share experiences. Visit Kathy Hodge's website.

Emily JanEmily Jan is an artist and writer who lives and works in Montréal, Canada. Born and raised in California, Jan has traveled to 33 countries and lived in four, including South Africa and Mexico. She draws inspiration from the eclectic experiences of a life spent largely on the road as well as from the culture of scientific inquiry that characterized her upbringing. Jan’s work uses the local and the everyday to create bridges to the faraway and the fantastical. Sara TabbertLichen Study I found these lichens in the high country on my hikes in the park. I liked the way their structure suggested so many kinds of motion - rolling, blowing, drifting - and I spent a lot of time arranging and "re-arranging" their shapes in my sketches and my mind. — Sara Tabbert, 2008 Sara Tabbert is from Fairbanks, Alaska. She was raised in Fairbanks and returned to live and work in her hometown in 2000. Her print work and carved wood panels are included in public and private collections across the state. In 2008 she had a solo show at the Anchorage Museum and in 2013 she received a project grant from the Rasmuson Foundation. This year she was one of four Alaskan artists selected for Rasmuson’s Artist in Residence program and will be spending June and July working at Zygote Press in Cleveland. In addition to a summer residency in Denali in 2008, she has been an artist in residence through the National Park Service in Zion and on Isle Royale. In addition to studio work, she works actively in the state’s Artists in the Schools program and enjoys the opportunity to meet and work with young artists. Visit Sara Tabbert's website. Kathryn Wilder1.

Alaska is on my mind. In September, when my son Tyler was last visiting me in Colorado, where I live in the southwestern—desert—corner, we spoke of longing for Alaska. It struck us as strange since we were in that far northern land in March, but we’d both been thinking about it, longing to go. To be there. To feel it again, see it, hear it. Northern Lights. Maybe a wolf. Then I read of a friend’s experiences of Alaska over the years. His words took me there, even though his experiences were extreme—climbing Denali to its highest summit—and mine were mild. It’s the heartness of it—of the place, of his rendering—that gutted me. I reread my own journal entries, wishing I’d written more. That’s how I regenerate experiences—rereading my own random scribbles, remembering. Now I remember by talking to Tyler and reading someone else’s words. Also, as our year tilts toward its own version of cold, I remember Alaska each time I don baselayers of clothing—silk long underwear beneath my jeans. 2. Even though I live in Colorado, the cold scares me. I theorize that my body neglects my extremities due to low blood pressure, and that this layer of fat insulates not, despite what people claim—instead it gets cold and the cold seeps inward, slowly wrapping my body in hypothermia-threatening chill. So when my application for a summer residency at Denali National Park and Preserve was answered with an invitation to go as winter Artist-in-Residence, I panicked first, said no second, and only as a third thought thought to be grateful. “Really, no,” I said to the park people, explaining my cold phobia. They coerced me gently into discussion, telling me that the residency started in late March, and at that time of year the nights and days are of equal length, spring tiptoes to the edges of things, bears and hoards of flies and people aren’t out yet, and they could loan me snowshoes. My mother said go. My older sister, who visited Denali one of the summers her daughter worked there, said no. Both know how cold and I interact. Their bodies support my low-blood-pressure theory. My younger sister said, “This is an important opportunity.” I dreamt of bears—a sow and five cubs—probably black bears though the sow and two of the cubs were blond. I have never seen a grizzly. Or a brown bear, as I would hear the species called in Alaska: All grizzlies are brown bears but not all brown bears are grizzlies, they say. Ready to decline the offer, not because of a bear scare in the night but because of the cold, I called Jay Elhard, Park Ranger and Interpretive Media Specialist as well as partial coordinator of the Artist-in-Residence program. “I’m cold in Colorado right now,” I said, the woodstove ablaze, the propane backup heater glowing. In winter in Colorado I have a rather large carbon footprint. “Denali is a dry cold,” Jay assured me, which meant its cold feels less cold than wet cold. I told him I regretted that I was going to decline because, thinking of my younger sister’s words, “What an opportunity.” But I’d applied for summer. For the light and water and wildlife of Denali in summer. That made sense. That is me. “It’s a huge honor,” I said to Jay. A cold time of year, I thought, winter. But there would be moose. Maybe a bird sighting or two. Jay said, “The wife of one of the Park Service employees saw a lynx in a tree just the other night. She watched it climb down face-first.” A lynx. It had paused for a snapshot. I found the photo online. “I can bring someone,” I told my mother. “Whom would you take?” she asked, though she knew. “Tyler.” My twenty-eight-year-old son, surfer and snowboarder and self-employed. Meaning he kept his own schedule. A Maui boy—a surfer who has also found a home on the snowboarding slopes of Colorado and California and has learned how to stay warm—even Tyler had doubts. But while I stay indoors between ranch chores on the cold days, my winter goal that of getting the house and me warm, he goes outside in the snow and cold and snowboards and plays and takes my little grandchildren sledding on our little Colorado hill. When I called Tyler to say I thought I would decline, he surprised me by saying he wanted to go. And so I said yes. 3. My mother was thrilled, but that night I woke in the middle of it thinking about keeping the rustic, historic Upper Savage Cabin, in which we would stay for four days of the residency, warm through the night with an inefficient woodstove; about how I would have to go outside to pee, the option of choice over peeing in a pot in the presence of my son, as there was no running water at the cabin, ever; and how to warm up after treks outside—because I would have to go outside, even in cold, not just to pee but to see that northern world, look for tracks, follow the path of a frozen river. Tyler and I spent hours perusing Patagonia and REI online. With his guidance I shopped from the skin outward, starting with the lightest baselayers. My fear melted somewhat as my suitcase filled. We worked out travel details—I would fly to the Bay Area; we would repack, combining gear and drybags, and leave for Anchorage from there, our heavy luggage in tow. 4. Sick in Cicely. There’s a ring to it, though it’s not true. There is no Cicely, Alaska. Like millions of other people in the 1990s, we believed in Cicely when we watched the weekly episodes of Northern Exposure—we believed in the place and the people, the personalities and characters, the strife, the camaraderie, the love. In my little group of friends some of us had TVs for watching video movies but only one of us got channels. On Tuesday nights we’d troop to his house, which smelled of popcorn and cigarette smoke, and settle onto his big L-shaped couch. That was perhaps the most communal I ever got, and the truth is I loved it. I felt as if our circle of friends mirrored the show—snow and dogs and adults in the script, romances flaring up and dying, intellectual discussions prompted by the philosopher-DJ Chris on the show. We knew Cicely was a fictitious town and that much of the filming took place in Washington State, but that didn’t matter. For an hour a week we were in Alaska. I think for both Tyler and me the real Alaska started on the plane, which slid toward Anchorage and darkness simultaneously. But it was light enough and white enough outside to see the peaks piercing clouds, and the occasional glacier. Everything beyond the glass looked white and tall and sharp, and we wouldn’t know until later that these impressively vertical mountains were only about 4,000 feet above sea level. We dropped out of the clouds to the flat expanse of outlying Anchorage. I mean really flat, though every horizon held those incredibly rugged, completely white peaks, snow reaching from summit to sea. My friend Mary met us at baggage claim after patiently waiting for the hours-late plane. She drove us to her house in Eagle River, where her husband, a judge, was barbecuing fresh Alaska salmon on the upstairs balcony. Thus began our own episode as we listened to true tales of small-town Alaska, including Mary’s beginnings there, driving west after college as far as she could go, and then north. North to Alaska. She never left. It is true that I am sick. Sick not in Cicely but now in Denali National Park and Preserve. Predictable after travel, three of four flights delayed, sleeping on different beds and couches in different temperatures, cold by day, either too cold or too hot at night, and I started with no reserve. I started the trip the day after I put Cojo, my sweet and faithful Border collie, down. 5. There’s no way to describe this beauty yet that is my job. Everywhere we look there is beauty. In every direction, all the way around. No wonder 450,000 visitors come here every year. We are but two. I am sick. We spent too much money on groceries, advised repeatedly to make sure we had enough food. Which is not why I am sick. I got too cold. After driving up from Mary’s house north of Anchorage—and shopping too much, and stopping in Talkeetna for the night and gawking at snow and mountains and three rivers and saying their names over and over again—Chulitna, Susitna, Talkeetna—and walking on a narrow bridge beside the train-track bridge with a sign that says to keep it open for the people commuting to town by snowmobile, which is the only way they can get to and from home—now we have arrived and need to unpack our too-much food and make our home within the national park homey and then get out into Denali. I am also tired. And a little disappointed to discover that even at this main camp residence—C Camp, our home base for the next week and a half—we have to go outdoors to a different building to pee, shower, and wash dishes. Somehow I did not figure that out from the e-mails exchanged and information sent. Somehow I did not think that of course they can’t leave the water on in all these cabins clustered here for summer help. Even living in a frozen land myself during winter, I did not think about this. Tyler and I will spend the next days drinking far less water than we should to avoid that middle-of-the-night trek. Having checked in with park personnel and received our instructions—basically, do whatever you want, within park rules—we unpack the food hastily, turn up the wall heater, and jump back in the 1998 Subaru Forester Mary and her husband have so graciously loaned us for this adventure. We take to Denali Park Road, our first of dozens of trips up and down the fifteen miles open to us. And that’s when we first see it. Her. The High One—the highest peak on the North American continent. The peak that re-found her name after a ninety-eight-year interim of being called Mount McKinley for a president-elect who had not viewed her. Bare months before our journey, President Barack Obama officially renamed the great mountain in honor of the people who have known her best and longest—the people who have lived within her circle for countless generations—and now she is again appropriately called by her real name: Denali. We round a bend. “Look!” I say. Tyler slams on the brakes. No one else is here—no tour buses, no cars—just us and a road and a mountain so magnificent we cannot speak. Tyler steps out with his cameras. I get my journal. Before us the eastern base of the massive Denali reveals itself in the late-afternoon (6:21 p.m.) light. Soft clouds cover the sky—clouds I don’t know. Not cumulus or cumulonimbus, these are mostly one big cloud, like fog but high, and then in front of Denali float little saucer clouds, as if a whirlpooling air current between the great mountain and the mountains closest to us stirs the air to make them. I can’t believe I will say this but it’s like the carnie making cotton candy, whipping the paper cone around in front of the pink sugar mess to form a pink cloud. Nowhere else do the clouds have definition. They are like soft smooth draping gray silk. Yes, a mixed metaphor, to match this mixed sky. 6. The Denali Park Road—barricaded near Upper Savage Cabin (the barricade easily moved) and completely closed at the bridge over Savage River until May—is our entry into this magical world of national park. The road curves with the contours of the land, following frozen waterways we cannot see in the cleavages of hills and depths of snow; it passes through white and black spruce forests, which open to a broad valley amid these rounded hills, backed by mountains everywhere. Each day we traverse the fifteen miles of road, except when prohibited by snow, looking for wildlife and the details of Alaska, and so each day we observe the Savage River at our turnaround spot. At first the “river” was simply a field of snow and ice under a bigger field of snow and I couldn’t tell its character. As the days crept toward spring and the water beneath the snowfields began to melt and move, the shadow of water under snow became apparent and we can now see that this is a braided river, two main currents meandering across the valley floor collecting drips and piddles of snowmelt, following the slight gradient toward the bridge, where they join and become a single current carving and crashing through ice that has held it captive for months, and then descending into a canyon beyond view. 7. Last night, chasing the Northern Lights with Tyler until 3 a.m. Today, noon, Denali shows in all her splendor. Not a cloud, saucer or otherwise, touches her face or edges. For a long time we just watch her, and even though we don’t know this is the last time we will see her fully, we feel blessed. I call my mother to tell her about the Aurora Borealis. She has longed to see it for herself, for years; now, at eighty-something, she thinks that perhaps the only way she will experience it is through us. “It’s like seeing music being played without hearing it,” I say, waves of chartreuse building and fading in my mind. “Like an orchestra without sound.” Purple edges float in. “I don’t know anything about music,” I tell my mother, “but I see this: visual music in the sky. And like live music, it’s gone the moment it’s made.” Like water, I think. I have watched rivers move as single beings but each drop that passes is never repeated. Putting it in language changes it. The language becomes the thing, while the drops of water and arcs of Aurora have long since disappeared. Tyler goes out after midnight each night with his camera, learning how to capture images of this thing that has captured his heart. This beauty. I’m sick and I go, too, straining my eyes and neck and resistance to cold in hopes of catching the rolling, fleeting colors of silent music. 8. An outsider inside Denali National Park and Preserve—that’s what I am, what we are. We don’t know this place—Denali or Alaska—and have no reference for it. For the sizes of things—moose bigger than mustangs. The colors—the night sky colors, the moon-flooded snow, caribou. The climate—the cold, which is cold (when someone says it’s not so cold in Alaska because it’s so dry, ask them, dry compared to what? Compared to the high desert country of the Colorado Plateau, Denali feels rather wet). Climate change—we straddle the Spring Equinox, where day and night match each other in length, and we ride the cusp of the changing seasons, but everyone we meet tells us there should be more snow, still-frozen rivers, no over-35-degree days. Parking lot snow turns slushy, then freezes. I stay sick. I stay hopeful, too, wanting to see all the Park’s winter wildlife. But wildlife does not appear because you want it to. It appears because it’s going about its life with complete disregard to yours. You’re either there to witness, or you’re not—it doesn’t care. This may not be true of all species of wildlife but it appears to be true of caribou. They seem completely indifferent. They lie down within sight of the red metal moving box containing two two-leggeds down there on the road. The Park Service where I live says that mustangs in the wild are not wildlife, but adult mustangs will not lie down in the presence of humans. Moose seem to pay more attention to us than the caribou do. They look askance and move deeper into the willows. The tracks of both are hard for me to decipher in the deep snow, especially when sinking to my thighs while attempting to do so. At home I know cattle tracks from elk tracks and certainly elk from deer. Their poop, too, easily identifiable. And all but the cows move away from human presence. At home all but the cows are hunted. Here I see wolf tracks near old moose tracks. Moose and caribou are hunted, too, even in the park. Hoping as I do to see the lynx doesn’t mean I will. And just because scientists in a helicopter spotted nine wolves, some of them collared, feeding on a dead moose, doesn’t mean we will. There are no guarantees here, each sighting a gift of timing. Nothing anywhere says I’ll hear a wolf howl, my desire minute and meaningless in the grandeur of this land. 9. I do not tire of watching, through binoculars, moose eating. A moose’s upper lip, all muscle like a horse’s, will grasp the narrow-leafed willow branches and pull a single branch down between both lips, stripping it of last summer’s dry leaves. I want to touch the velvet muzzles of moose like I do my mustang’s muzzle. Nor do I tire of watching caribou. Amid this carnal landscape they blend, their legs dark brown to black like tree trunks and this rich earth, their throats white as sunlit cloud, their sides muted and ribbed like last year’s willows. Today we watched fifteen caribou down there in the bottom of the valley that is maybe not really a valley but the wide riparian corridor of the braided Upper Savage River—willow stalks placed intermittently have me wondering if it is river bottom or valley floor beneath the snow, beneath the hooves of fifteen caribou nosing along as if nuzzling new shoots up through the ice. We’re told that of the park’s caribou herd, which totals about 2,800, only five percent are acclimated to the noise and activity of the park—those you see near the park headquarters. “The rest of the caribou are elsewhere.” “Like thirty-five miles elsewhere,” Tyler says. The park is just so big. I still want to see a snowshoe hare. Red squirrels. I want to hear a wolf howl. I want to see a lynx. Dall sheep. I want to see a wolf. A whole pack. 10. Tyler e-mails my mother some photos of the Northern Lights. “Aurora f*ing Borealis” he puts in the subject line. She calls to tell me it’s the best e-mail she’s ever received. 11. My job as Artist-in-Residence is to write, yet rarely have I found myself so wordless. I am dammed not by writer’s block but by writer’s overwhelm, my words as meaningless as want in the face of this place. Today Tyler and I went to Upper Savage Cabin to meet with a botanist and the other Artist-in-Residence, Sara Tabbert. Sara is a printmaker whose carved woodblocks carry the depth and texture of the natural world that inspires them, and there on the old plank table in the tiny ninety-year-old cabin stood two nearly completed pieces, with a third work-in-progress lying flat, ready for us to leave and the quiet of the white spruce woods to carry the artist back into the space of her carving. Human voices led us away, followed by the chattering of an early spring red squirrel, the scrawking of a raven, and my own silence. Back in the Forester, Tyler and I talk about the cabin. It is small—a double bed, the old table and woodstove, and between them a few feet of floor space for sleeping. Two chairs. We’re thinking maybe I’ll stay there alone, giving us both time for our own time in Alaska. 12. While weather warms each day this side of the Spring Equinox, snow still covers much of the country we see from these few miles of Denali Park Road. The mountains of the Alaska Range surround us, quite literally—backed in the west by Denali herself, mountains dominate every inch of our 360-degree horizon. As spring inches its way into the park, dark outlines of ridges poke through their snow cover, and south-facing slopes become textured with alternating white fields and patches of dark moist soil. The dominant white spruce, trunks brown and branches green, further texture the lower slopes, and in the bottomlands the narrowleaf willows grow. Each day the water sounds different. Frozen to melting. 13. I saw a bird yesterday—a gray jay. I read a book. I heard the wind. I startled the red squirrel on the porch of Upper Savage Cabin, her flight response so fast I couldn’t focus on color, ears, or even size, just a startled mid-flight stop and hasty restart. Yesterday I walked, twice, read the Savage Cabin Trail interpretive signs, walked down the musher’s trail and back to the cabin and back down to the road to the barricade and back to the cabin along another trail. This after Tyler dropped me off as planned and left to rendezvous with my niece’s ex-boyfriend Kevin. By the end of day it was darkish outside, darker inside, and making dinner—a salad—in propane-lantern and headlamp light was possible but slightly annoying. Better to do dinner prep before sunlight disappears from the cabin. Like on the river, before the canyon dims. Read more and slept and woke three times to pee outside—at least here I didn’t have to dress fully for the trek or possible sightings by park people—and stoked the stove, and the cabin was 54 degrees when I rose at first light. So I stoked it again and went back to bed, read, dozed, and woke up sweating. Now I’m outside on the porch, in fleece pants and down jacket in addition to baselayers and hat and boots and shades but minus one glove so I can write. Warm sunshine pushes through clouds toward me while the wind stirs the white spruce and willows. That’s all the botanist identified the other day, though I want to think there must be more species. If these are willows right here, their trunks are six inches around. I can see only the mountain far across the valley, from its tree line to its ridgeline white with snow. The rest of the view is trees and snow, the trees protecting this porch from wind. I am waiting for Tyler. I don’t mean to be but I am, I can feel it. Voices drift up, maybe from the parking lot down below the Park Road, maybe from the trail. Which means people may appear. Yesterday I hid when they made the curve just before the cabin—three different sets of people, three times of hiding. The Park Service literature says to be hospitable but I didn’t want to talk to strangers. Only to Tyler, and he was already gone. I didn’t write that part. Maybe I will, maybe I won’t. I don’t want the feelings back, I know that much. 14. This is called a wilderness cabin. And maybe, in the depths of winter with the road only plowed the three miles in to park headquarters but not beyond, then when those staying at this cabin are mushers out with their dogs for weeks at a time, maybe then it feels wild. No roads, traffic, people’s voices, only the wind in your ears as dogs lunge forward through the snow carrying supplies to other backcountry cabins and camps and stations, when your food and gear are what you haul with you and no one in a car will come pick you up if you’re in trouble or lonely. If that is wild, why have I felt it in other places, places I have accessed by hoof or foot or tire, river or sea? Even my own log cabin has a flare of wildness to it, off the grid and an hour and a half from town no matter which way you drive, but driving you have to do. Like here, there is no Internet or phone service, though I have a water catchment system and solar power. Here in this park, in this big rugged mountain country of snow and stream and thaw and freeze, traveling along these fifteen miles of Park Road, do I not feel the wild because I am in a car, tires rolling along on asphalt, wildlife spotted through a dirty window? We have stepped out and walked, and had I not arrived sick we would have hiked more. Yesterday from Savage Cabin I started on a hike toward timberline, which is low here so I didn’t think I had far to go. I wanted to see more than the close spruce and willows that surround the cabin—needed to, as melancholy had set in. Beyond the outhouse I struck snow nearly three feet deep—no snowshoes, just these big snow boots—and with each step I floundered and teetered and sometimes fell, thinking of the moose that just push on through. But a mature bull moose weighs 1600 pounds—like more than ten of me. I retreated toward the cabin and a park trail packed down by snowshoes and cross-country skis. Then hit the road, half of which had been plowed clear of snow that had fallen in the night. Even though I saw not another soul, walking on blacktop is no cure when searching for something that feels wild. I left the road and followed the trail of mushers off toward the valley floor. Wind sang around my ears, I was cold then too hot, and kept walking along the snow trail, stopping periodically to search for camouflaged caribou or moose in the willows. Or tracks—anything. But it was just mountains and me and cold wind blowing down and then I heard something different. Not the quiet of snow but the sweet rush of water freed from ice and heading toward spring. Soon I stood looking down at water as clear as a Sierra Nevada stream—something rare in my part of the West—and I watched it slip over rocks of polished white quartz and sparkling feldspar as it meandered downstream. Sweet, sweet water, water I wanted to put to my lips and slurp, which I didn’t do because I was bundled up so tightly against the cold that I saw myself spilling into the stream if I tried to bend over. Instead I just stood there, listening. Listening to water, to wind, to the breath of life in this north country. I didn’t feel wildness. I felt peace. And then far off I heard the snowplow coming back, grating along as it cleared the other half of the Park Road. Is silence a definition of wild? Or, not silence perhaps but the absence of human-made sound? Which I will never hear because I carry human sound with me wherever I go, yet sitting on the stoop of Savage Cabin or the Colorado log cabin porch and listening to wind and birdsong and squirrels or chipmunks scratching along in the pockets of no road traffic or air traffic, I feel something precious, something sacred, and it can stand in for wild if it wants. 15. I watched Tyler leave. Before the flashes of his new, ocean-blue, supremely down jacket disappeared between the branches of white spruce lining the trail I found myself gasping for air, thinking I might puke from pain. From fear, loss, longing. Closing the door, the cabin instantly shrunk tightly around me, its dark wood walls and low ceiling and small windows with their close views of tree trunks wrapping round and round my chest and throat. I don’t understand it. I am alone so much of the time. I choose alone. This old Alaska cabin should feel no different than my choices at home. But it did: smaller tighter darker. And, I am often alone, yet not alone. Always there are dogs. There are grandkids smooshing their faces against the window in the door to see if I am home. There is my other son Ken doing chores with me morning and afternoon, his wife bustling through with compost and chicken feed. There is livestock; there are horses. The dogs. Alone, I am not really alone. The dogs. I closed the door to Savage Cabin and there were no dogs. None inside with me. None outside. I had no dogs. And with that came the awareness that even when I got home, I would be short a dog—Cojo. There under the desk or coffee table, beside the bed, outside the bathroom door (inside if I’d let him). Ever-present, for those many years—Cojo. There through the loss of Rebecca Dad Ed, through moving and leaving and moving and losing, deaths and births—there for all of that—my dog Cojo. I could not bear to sit with the feeling. Did not want to be alone. Thought about my life, about choosing alone (with dogs), about how maybe alone is not best for me. I thought about how the best part of this trip was Tyler. The flash of his ocean-blue supremely down parka is better than sunlight, moonlight, caribou and Denali and even the wolf howls we’re not hearing. The beauty of his smile, his giggling laughter, his excitement over the things of Alaska large and small, his obsession with the Northern Lights, his e-mail to his grandmother—Aurora f*ing Borealis—Tyler! This trip would not be the same without him. Except this part, here at Savage Cabin, without him. I almost cried when he was here, when he was wanting not to leave because he could tell I was trying not to cry. I’m over bravado. I came here with Tyler and if this cabin is too small too dark too confined for both of us, I choose Tyler. I cannot leave. He has the car. Will show up sometime to check on me. Will want to leave again. Will I go with him? Or stay another night? To prove something—to whom? Good grief I know I can stay away from people for days, weeks. But without dogs and without views and without snowshoes and knowing Tyler is thirteen miles away without me—yesterday I did not want to stay so bad I could taste it, them, my own tears caught there in my throat. And I stayed and cried and missed all my dogs especially Cojo and so I read and wrote and read so that I did not have to sit in the overwhelming sadness and do I really want to do that again? Ever? This part of the park is not wilderness. It is not wildness. It is a national park—beautiful—sheer utter complete total beauty—to be shared. With my son. I hear voices again on the trail and jump up to hide in the cabin and then I see that flash of ocean blue. I’m holding back tears when Tyler walks around the curve in the trail, and behind him, Sara Tabbert, the artist part of our Artist-in-Residence residency. They walk up toward me together, chatting and laughing, and Tyler hugs me and then I do cry, damn it. And I confess that I don’t want to stay. Sara has already done it—stayed her four days at Savage Cabin. She even stayed an extra one, not wanting to leave. The days were warmer and she worked outside, and my stay happened after a snowstorm hit and the days were colder again, and she cross-country skis and I don’t even have snowshoes. “You don’t have to stay,” Sara says. “But…” “It’s your residency. Spend it how you want.” For an hour we visit inside the cabin, the door open to the freshness of outside, and I almost don’t notice the cold. A luscious hour of people and companionship and camaraderie, and I feel like Northern Exposure’s Joel Fleischman deciding I like being around people after all. Tyler helps me pack and shut up the cabin and we drive back to C Camp, and there Kevin, ex-boyfriend of my niece, joins us and we go to dinner at 229, the restaurant where my niece worked and Sara carved the background of the bar and even the beer taps and everyone knows Kevin and stops at our table to say hello and we’re seated next to the musher whose dogs were attacked and killed during the 2016 Iditarod and I want to tell him about Cojo. Which of course I don’t. We’re seated there for hours in the warmth of wood and good food and Sara’s carvings and Kevin’s friendship with us and with all those people he knows because he is a part of something there in Alaska, part of the world that spills out of Denali National Park into the lives of the people who reside within the great circle of that grandest of mountains. Denali. 16. The next day we venture again outside the park boundaries, to see more than the fifteen miles of Park Road. We stop to look at a river, the Nenana, which absorbs the waters outlined by the Park Road and carries them toward the Tanana to the north. Though still frozen along its banks, the river already rushes with runoff. Highwater marks of previous years show its massive muscle and force in whole downed trees stranded many feet above the present current, and we remember the story Kevin told of almost running it at an estimated 40,000-plus cubic feet per second. He stood there looking at the raging water, and turned away. His friend ran it without him. Sometimes the adventure just isn’t worth the risk. Looking at the river’s story told in the wreckage along its banks, we agree that Kevin made the right choice. We drive on and that’s when we see Dall sheep, way up high above the river. We stop again and park and venture closer, though we’re still far beneath the sheep. No vehicles appear on the road and for a while it’s just Tyler and me and seventeen sheep white against the gray shale cliffs of the high canyon, and when one jumps to a new spot from which to browse the invisible-to-us vegetation, we hear a rock fall and bounce and crash its way to the river. 17. It’s the day before the last day. We want to get outside, and inside the place—out of our cabin at C Camp and into the air and cold and frozen edges of Denali. And so we go, again, to winter’s end of Denali Park Road. The barricade has been removed, these last two miles of Park Road now available to all. We have walked onto the bridge over Savage River many times by now, watching the river breathing with the changing seasons. We have walked up to Savage Rock and around. Tyler saw a butterfly up there. Regrettably we did not hike from Savage Cabin to the rock and river, and now we haven’t the time. So we decide on the Savage River Loop Trail, a short walk downriver and across a bridge and back up along the far bank. We’re in our ocean-blue (Tyler) and maroon (me) down jackets, our good heavy snow boots, baselayers and gloves and scarves and all the layers in between, and we have those ice-gripper things attached to our boots, mine the better of the two pairs loaned us by the park, and we start walking. A couple is in front of us, European, maybe French, and eight visitors unload from a van, stepping into the cleared parking lot near signs and views. They photograph both Savage Rock and River. Denali is invisible, having not shown herself since our first days here. The couple does not interact with us, which is fine by me. I have already learned that Tyler makes the trip for me, and that the sweet conversations with Sara Tabbert, and time and dinner spent with Kevin, have added to a growing sense of warmth and community. I smile at the visitors as we pass them and do not speak, and watch my feet as they pockmark deep snow, and look up at majesty every few moments. The couple before us veers off the trail, which is barely visible under winter, and heads toward the river. The river is a mixture of seasons—in some places it’s frozen over; elsewhere it’s a jumble of foot-thick ice blocks, blue water splashing up and under and around in an urgent move to get downhill. The couple steps toward the mayhem. Tyler and I look at each other. “They’re not really going to cross that?” I whisper. Foot by foot they head toward a snow-covered ice crossing. They have walking sticks, a camera. We just have the camera in Tyler’s cell phone. We decide to stop gawking and mind our own business, which is to take our own careful steps downriver. We reach the point where they veered. Ice. A slurping slippery ice cap frozen over snow. Water that has spilled and dripped from the sloping canyon wall above has combined with seasons to make this ice flow. It has yellowed with age. So have I, in that moment. I look to our couple—they are stepping carefully across the iced-over-in-that-place-only river. Upriver and down the river charges, freed by these last warm (a relative term) days. I know what a strainer is. It’s a nightmare for boaters. A place where tree branches or other obstacles reach out over the river, and if your raft or kayak slips under them, and the current beneath you pulls you more tightly into the tangle, you could be toast. Wet, soggy toast, but still done. I don’t know what an ice-made strainer might be called, but I see them lining this river. A fall into the current would quickly take an instantly chilled and weakened victim under ice. The water is not yet deep enough to carry the victim along under the ice. The river’s strength is in its cold and current, strong enough to pull you under—under ice—but not strong and deep enough to free you. Trapped under ice. I look away. Tyler has begun crossing the ice-cap thing, which covers many yards of the “trail.” Signs told us that the bridge is a mile down. I don’t want to turn around, and I will not walk across the icy river. I follow Tyler’s steps. The “warm” day has melted the surface and the ice is like wet slickrock—slick. My stomach shrinks. A fall would take me right down to that cold, ragged river. Another step, and another, so slowly I imagine Tyler’s impatience. And suddenly I hear a gasp and a cuss word and ocean blue flashes before me and I probably scream as I freeze in my steps and watch Tyler as he struggles to right his balance as he gains unwanted momentum toward the river and then his big hiking boots with the lousy ice grippers are beneath him and he’s sort of squatting midair as if he were snowboarding, aiming for a jump, when he’s actually aiming with all the skill he can muster for the only bush on the whole side of this canyon; he skis on his feet right down into it. And it stops him. He sits down in the snow, breathing hard. He swears. I haven’t moved, not one foot, one inch. Slowly Tyler stands. He’s tall and this takes a while as he steadies his feet at the base of the bush. “What do we do?” I say when he’s fully upright, and he starts stepping up the slope, working each foot as deeply into the ice as he can before applying his weight. I look back up the canyon, at the couple safely walking up the trail on the far side of the river. I look before me, behind me, beside me. I am smack-dab in the middle of the ice thing that Tyler slowly ascends. I swear. Tyler reaches safe snow on the downstream side of the ice. “You have to move,” he says. “No,” I say, “I don’t.” But I know I do. Moving toward my son is the only option I can see. He coaches me across the ice, step by step. And I make it, Tyler there to steady me as I reach the welcome thigh-high snow, which holds not only each foot but each leg firmly in place. The next half-mile of snow- and ice-covered-in-places trail feels relatively easy. We wade across the snow-covered bridge. Below it the river charges through ice. Tyler wants to keep going downcanyon. “I’ll wait,” I say, any youth I might have retained or adventurous spirit having faded along with the adrenaline rush of watching my son ski on his big feet toward Savage River. I don’t wait for long, because I need to move or cold will settle in. I start the mile back upriver slowly. As I walk past a clump of willows, a burst of white snow jumps up and flutters off. I can’t really see it until I do, its two black eyes the only contrast the willow ptarmigan has with the snow. Now I wait for Tyler, to show him this blending snow-white bird. That night I taught my workshop to a small group of local writers, two of whom originated on the Colorado Plateau—we connected previously at Sara Tabbert’s woodcarving workshop and now gabbed like old friends. When Tyler and I told the tale of his ski toward the frigid river everyone laughed, me with pent-up relief, them because they thought it was funny. And they said, “Oh, that’s aufeis.” It’s not ice rock or ice cap or anything else ice we might have thought to call it. It’s aufeis, translated as “ice on top,” and forms when water emerges from the earth as in a spring or in places along a river, reaches the freezing temperatures of outside, and, well, freezes. As more water leaks forth, layer upon layer of ice forms in these places. Aufeis is simply part of Alaskan terrain, like snow, like glaciers and mountains, like frozen and thawing and flowing rivers. 18. Tyler took a photo of me stranded there in the middle of the yellowing aufeis. I bear the same expression as in a photo he took of me with the park dogs. One of the sled dogs has jumped up on me and holds me with his paws on my shoulders; another has grabbed my knitted scarf in his teeth and is pulling me in the other direction. I am stuck. Stuck in Alaska. And I don’t mind. But it’s temporary. We drive south the day after aufeis, meeting Mary and her husband in Talkeetna, town of three rivers—Chulitna, Susitna, Talkeetna. Mary and her husband are headed to Fairbanks and we are headed to their house, where we will stuff our extra food in their refrigerator, shower and repack, pee without going outside, doze for three hours, and then leave Alaska. 19. Bright yellow daffodils and the pastels of orchids add color and the fresh smell of earth to my mother’s small apartment. Outside her sliding glass doors sunlight breathes warmth into the afternoon, and potted plants bring greens and reds and orange to her palette of springtime, so different from the shifting world of winter white we just inhabited. Our luggage clutters my mother’s living-room floor—here we will spend our first night back in “the lower forty-eight.” I dig deeply into a dry bag in search of clothes for a warmer climate, and Tyler sets up his computer so his grandmother can see the biggest screen. We trip over each other’s stories in our eagerness to share all with my mother and answer her questions. She and Tyler sit close together on the couch as he shows her hundreds of photos of the magical, musical Northern Lights. She is appropriately undone, not just by the sheer beauty of what Tyler shares with her but by his enraptured state—his own sheer beauty in his love of this new sky. Sometimes the adventure is worth the risk. The risk in saying yes to Alaska was nothing like the risk of running a river at incredibly high water, but for me it was big. It wasn’t just the cold that challenged me—it was the travel and being among so many humans when I am a recluse at heart, a lynx content to roam at my own pace and whim, watchful, elusive. But I’m also part herd animal, like caribou. Like horses. My band may be small but it’s where I belong. 20. Months later, walking through December snow in Colorado with my Denali-climbing friend, I shove my hands deep in the pockets of my maroon down jacket. There I feel soft leather. “My gloves,” I say, pulling them forth. “I’ve been looking all over for these. Haven’t seen them since forever,” and it dawns on me, “since leaving Alaska.” They are soft brown leather gloves, cashmere-lined. I slip a hand inside warmth and comfort, and turn it palm-up. The fingers of the glove are coated with a fine gray sheen. “Alaska dirt,” I say. My friend who ascended Denali lifts my gloved hand to his lips. “Glacier silt,” he says. Up there in Alaska I learned how cold and warmth are relative and that grizzlies are brown bears but brown bears are not necessarily grizzlies and that saucer clouds are called lenticular clouds and 20,310-foot Denali does actually make her own weather. I learned about moose lips and the colors of caribou and the Aurora f*ing Borealis. And that even if you see Dall sheep and a snowshoe hare outside Denali National Park and Preserve, it counts. I learned of aufeis. I learned that our national park system, begun a hundred years ago this year, holds both wilderness and family at its heart. And finally I learned this: You may leave Alaska, but like glacial silt that works its way into the creases of your leather gloves and your heart, Alaska doesn’t leave you. Kathryn Wilder edited the Walking the Twilight: Women Writers of the Southwest anthologies, and co-wrote Spur Storyteller Award finalist Forbidden Talent with Navajo artist Redwing T Nez. Pushcart Prize, Western Heritage Award, and Hawai`i's Elliot Cades Award nominee, her essays and stories have appeared in such places as Southern Indiana Review, bosque, River Teeth, Midway Journal, Fourth Genre, and Sierra; many Hawai`i magazines; and half a dozen anthologies. She has an MA in creative writing from Northern Arizona University, and is currently in the low-rez creative nonfiction program at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. She lives and writes among mustangs in southwestern Colorado.

|

Last updated: March 8, 2019