NPS / Nevin Kempthorne Early in the 16th century, Spain established a rich colonial empire in the New World. From Mexico to Peru, gold poured into her treasury and new lands were opened for settlement. The northern frontier lay only a few hundred miles north of Mexico City; and beyond that was a land unknown. Tales of unimaginable riches in this land had fired the Spanish imagination ever since the Spanish arrival in the "New World". They lured Hernando Cortéz to Mexico in 1519, followed shortly thereafter by Parfilo de Narváez to Florida and Francisco Pizarro to Peru. Many expeditions ended in failure, but there were enough successes to keep alive the dream that great wealth lay within the grasp of anyone with the opportunity to seize it.

Courtesy of The New York Public Library and NPS Such was the situation in 1536 when Cabeza de Vaca and three tattered companions, sole survivors of the shipwrecked Narvaez Expedition, arrived in Mexico City after eight years of wandering through what is now the American Southwest. Everyone listened intently to their story of an incredible land to the north comprised of seven "large cities, with streets lined with goldsmith shops, houses of many stories, and doorways studded with emeralds and turquoise!" Antonio de Mendoza, Viceroy of New Spain (Mexico), was anxious to explore this new land to determine if the stories were true. In 1539, he sent Fray Marcos de Niza to find out. Esteban, an enslaved African who was familiar with the Indians’ languages and customs in the region, led Fray Marcos on his journey. Fray Marcos returned to Mexico City in the summer of 1539 with the news that Esteban and some of his companions had been killed at the Zuni Indian pueblo of Háwikuh, the reputed site of the prosperous civilization they had heard of. Marcos also claimed to have seen the Seven Cities of Gold and that it was bigger than Mexico City. Though Fray Marcos' report was garbled and exaggerated, Viceroy Mendoza was convinced of the cities' existence. He promptly began planning an official expedition and chose his close friend, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, to lead it. Coronado had come to Mexico in 1535 and through his friendship with the viceroy and past successful missions, rapidly rose in status. After serving as a prominent member of the Mexico City council, he was appointed governor of the northern frontier province of New Galicia. On January 6, 1540, Mendoza commissioned him expedition commander and captain-general of all the lands he might discover and claim for Spain. The viceroy, however, counseled Coronado prior to his departure and cautioned him that the quest was to be a missionary undertaking, not one of military conquest.

On July 7, 1540, they arrived at Háwikuh, south of present-day Gallup, New Mexico, and first of the fabled Cities of Cibola. But a major disappointment awaited the Spaniards. Instead of a golden city, they saw only a rock-masonry pueblo occupied by Indians who were prepared to defend their village. After several unsuccessful attempts at a peaceful negotiation, the Spaniards attacked and forced the Indians to abandon the village. The pueblo, well-stocked with much needed food, became Coronado's headquarters through November. Fray Marcos, whose tales had raised so many hopes of wealth and fortune, was ordered back to Mexico City amidst a rising tide of anger and bitter resentment.

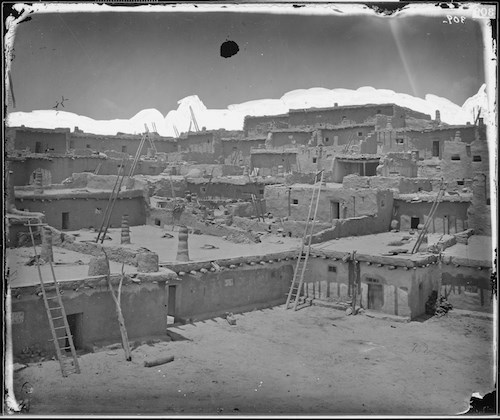

US National Archives and Smithsonian Institute. Photographer Timothy H. O'Sullivan, 1873. Public Domain. While at Háwikuh, Coronado sent his captains out to explore the surrounding region. Don Pedro de Tovar and his troops reached the Hopi Indian villages in northeastern Arizona while Garcia López de Cárdenas and his men traveled as far west as the Grand Canyon of the Colorado. A third captain, Hernando de Alvarado marched eastward past Acoma and Tiguex pueblos to Cicuye (Pecos) pueblo, near modern-day Santa Fe. It was here that they met "The Turk," a Plains Indian who astounded them with his tales of an unbelievably rich land further to the east, called Quivira. The Turk's stories renewed hopes among the Spaniards of finding the great wealth that had thus far eluded them, however, with winter approaching, further exploration had to wait until spring. The army wintered at Tiguex with the seemingly friendly inhabitants. However, the Indians' mood soon turned to open hostility when violations of hospitality and friendship were commited by the Spaniards. A series of battles followed, resulting in the Spaniards killing the occupants of one pueblo and forcing the abandonment of several others.

NPS/Roger Braden On April 23, 1541, the entire army set out for Quivira, guided by The Turk. After 40 long days of travel, Coronado sent most of his men back to Tiguex and continued marching northeast with a small detachment. Upon arriving at Quivira, near modern-day Salina, Kansas, they were disillusioned once again. While the agricultural civilization of the Wichita Indians was a flourishing society, their homes were thatched-roof houses, and they did not have gold or other treasures the conquistadors were hoping to find. Believing The Turk had lied to them, the Spanish tortured and killed him. Whether he had been purposely deceitful is a matter of debate amongst historians, and there is reason to believe misunderstandings had arisen because of faulty translations between the parties. In any case, Coronado and his men had had enough. They soon began their long grueling return march back home, mired in bitter disappointment at having failed in their mission.”

|

Last updated: July 27, 2025