Left image

Right image

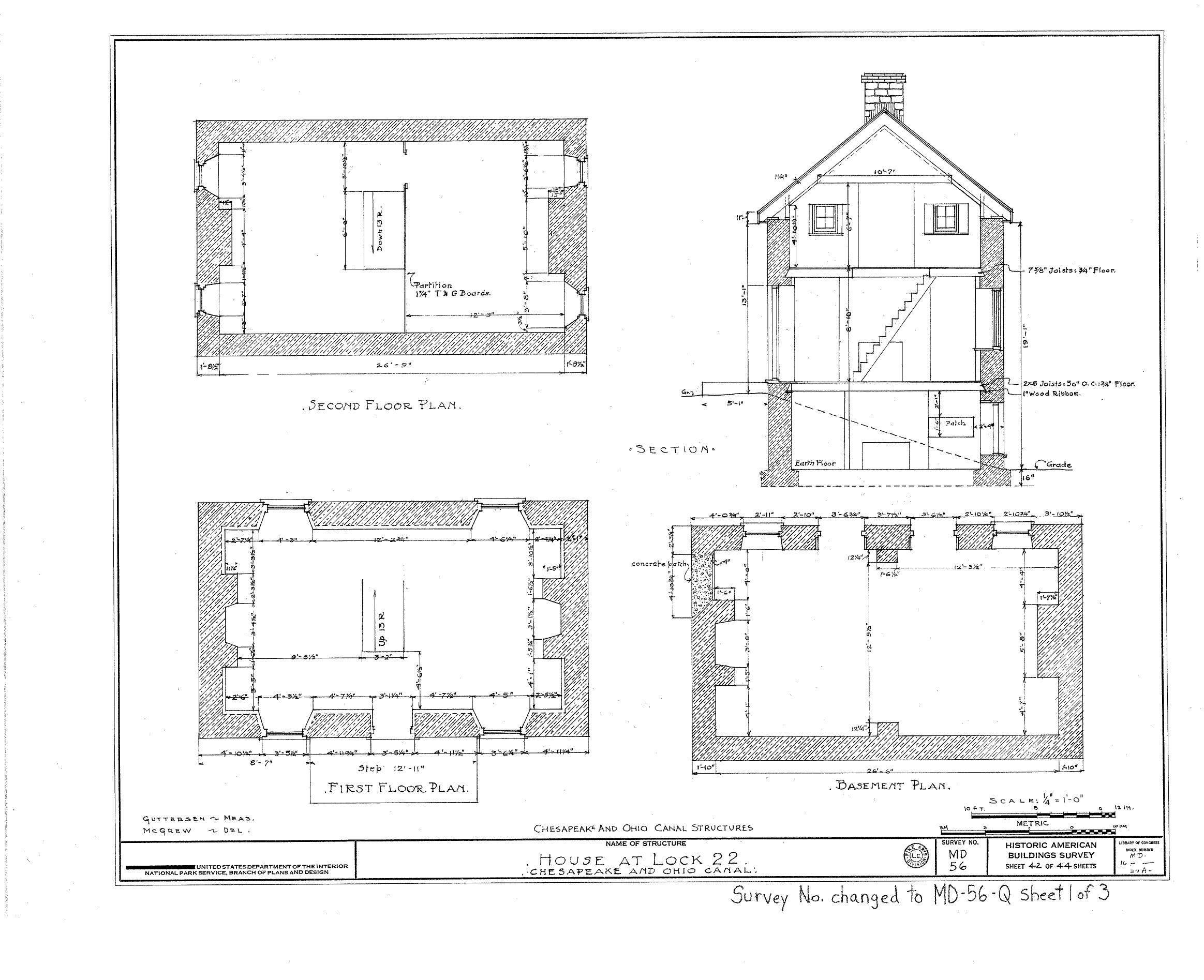

Lockkeeper Trading with a Canaller Lockkeeper Trading with a CanallerNPS/Harpers Ferry Center A Home for Whom?An important person in the day-to-day operations of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was the lock tender (Lockkeeper). It was his duty to open and close the lock gates (Lift Locks) and to lock the boats through. He could be called upon to render this service at any hour of the day or night, and as compensation he received his house, an acre of land for a garden, and $150 a year. For each additional lock under his care, he received $50 extra, but he was expected to provide his own assistants to tend them. Married men and large families were preferred for the job of lock tender as this meant more hands to do the work. Lockhouse constructionThe construction of the lockhouses reflects the history of the construction of the canal and illustrates some of the difficulties that the Canal Company experienced in building the waterway. The lockhouses on the lower end of the canal, built during the earlier years, are of mostly solid brick or stone construction. As the financial condition of the Canal Company grew progressively worse, it was necessary to resort to a number of expedients in order to cut costs. As a result, the lockhouses toward the upper end of the canal were of cheaper wood and log construction.  Lockhouse 22 Floorplan Lockhouse 22 FloorplanNPS

What are their historical significance?The lockhouses on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal are significant architectural resources, illustrative of the social, cultural and economic history of the waterway and the surrounding Potomac Valley. In these structures, lived the lock tenders who performed an important function in the day-to-day operations of the canal. Lockhouses during major Potomac River Floods Johnstown Flood, 1889: Landmark #26 Johnstown Flood, 1889: Landmark #26Library of Congress, The Johnstown Flood, May 30 and June 1, 1889, wrecked havoc on the C&O Canal, setting the course for the canal's closure in 1924. This titanic flood swept down the Potomac, the crest of which was higher than any ever before recorded in the history of the valley. The torrent swept away many lockhouses, storehouses and sheds, and many masonry structures were heavily damaged. Among the lockhouses between Georgetown and Seneca that were affected by the flood were the following:

The flood in 1889 left the canal a wreck and forced the Canal Company to go into receivership with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad emerging as the majority owner of the Canal Company bonds. Under the railroad, trustees were appointed and the canal entered its last period of operation. In 1924, after the railroad had captured almost all of its carrying trade, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal ceased to operate.  Flood. Spring 1936 Flood. Spring 1936Library of Congress, A minor flood swept down the Potomac in March 1936, causing extensive damage to the deserted canal. Included in the damage to the waterway was the destruction of numerous lockhouses. According to various reports, the following structures were either partially damaged or completely swept off their foundations:

When the federal government acquired the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal from the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1938, the National Park Service promptly set about to restore the waterway as a scenic natural recreation area. As an experiment, it planned first to re-construct the 22 miles between Georgetown and Seneca Falls. Two Civilian Conservation Corps camps were established on the canal to carry out this project. Within two years the 22 miles section of the canal was extended to Seneca. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Last updated: December 16, 2023