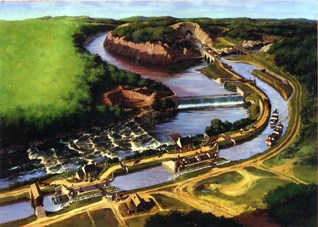

NPS Drawing On July 4, 1828, President John Quincy Adams turned over a spadeful of dirt during ceremonies at Little Falls, Maryland, and therefore began construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. It was officially the work of the C&O Canal Company, which raised about $3.6 million from private and public investors. Included among its stockholders were the federal government, the states of Maryland and Virginia, and the cities of Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria; all of them hoped the waterway would bring trade and therefore jobs to the region. As it turned out, events that day would affect the C&O in another way, because it was also on the 4th that work began on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O). From the start, problems slowed progress on the canal. The rocky ground embarrassed the president with three false starts, and foreshadowed how difficult construction would be. An acute labor shortage forced the company to recruit workers from other states and abroad. Construction scenes were often described as a dizzy stir of activity. Irish, German, Dutch, and English immigrants, promised a better life in America, worked long hours for little pay using primitive tools to dig the canal. Disputes arose with landowners who resisted efforts to purchase necessary land. A long legal battle with the B&O involving the right-of-way between Point of Rocks and Harpers Ferry slowed construction of both the canal and the railroad until about 1832. Inflation increased the cost of labor, materials, and land during the late 1820s and 1830s until they far exceeded the original estimates. Labor unrest among the predominantly Irish workers and the financial panic of 1837 added more difficulties, and between 1842 and 1847 construction stopped entirely. The canal was finally completed in 1850 at a total cost of $11 million, the original plan to extend the waterway over the Allegheny Mountains having long since been abandoned. The canal succeeded an earlier venture, led by George Washington, to improve navigation of the Potomac by constructing canals. The C&O was intended, as its name suggests, to connect the Chesapeake Bay to the Ohio River, but it never made it that far.

NPS Photo Boats began to appear on the canal soon after the first short section was completed in 1831 between Little Falls and Seneca. Sections opened for navigation as they were completed: Georgetown to Seneca in 1830, then to Harpers Ferry in 1833, to near Hancock in 1839, and finally to Cumberland in 1850. In October of that year, the first five boats filled with coal traveled the distance of the canal. Trade increased as other segments opened in western Maryland, and cargoes of flour, grain, building stone, and whiskey began to move down to Georgetown. Not until the canal reached Cumberland, however, did the tonnage increase substantially. Large quantities of coal from the Cumberland region began to be shipped, and by 1871, the peak year, some 850,000 tons were carried down the canal. Trade was so busy that at times more than 500 boats were in operation on the canal. Coal traffic then began to decline, however, as mining companies shifted more of their business to the B&O Railroad. A major economic depression in the mid-1870s and major floods in 1877 and 1886 put a severe strain on the C&O's finances. In 1889 another serious flood forced the canal company into receivership, at which point the B&O Railroad bought up the majority of C&O's bonds. The railroad had captured almost all of the canal's trade by 1924 when another devastating flood struck. This time no repairs to the canal were made, and its operation as a trade route came to an end. In 1938 the railroad sold the entire canal to the U.S. Government for $2 million, which placed it under the supervision of the National Park Service. The Park Service did some restoration under the emergency work programs of the 1930s, and other repairs took place in the following decades. In 1961 President Eisenhower proclaimed the canal a national monument. In 1971 Congress declared the C& OCanal a National Historical Park, thus conserving its historic and natural features for all to enjoy. Today, visitors can examine how the locks work, take rides in canal boats pulled by mules, and bike and walk along the canal's 185 mile route. |

Last updated: September 18, 2021