NPS Photo Rocks Reveal ChangeThe rocks of Cedar Breaks National Monument reveal the powerful forces of geologic change that have created the canvas upon which today’s remarkable landscape is painted. Standing at the rim of Cedar Breaks amphitheater, you gaze into a high-altitude wonderland of colorful cliffs and pinnacles. Yet the rocks tell stories of ancient seas, violent volcanoes, and a time when a visitor to Cedar Breaks would have found themselves afloat in a body of water the size of modern-day Lake Erie.

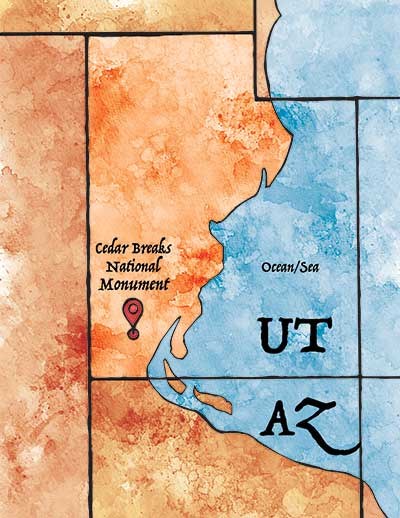

NPS Illustration by Shannon Eberhard Ancient Mountains & SeasHidden in the forested Ashdown Gorge lie the oldest rocks in the monument, relics from a time when Cedar Breaks would have been beach front property!

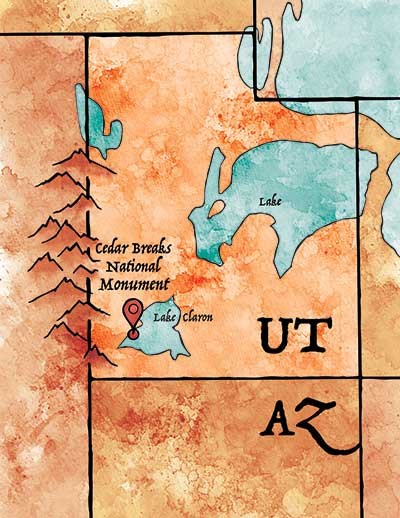

NPS Illustration by Shannon Eberhard Lake ClaronBy the end of the Cretaceous, the sea had retreated and the Rocky Mountains were beginning to rise to the east. Now surrounded by mountains on all sides, Southwest Utah became a closed basin home to ancient Lake Claron. By about 60 million years ago, streams were bringing sand, silt and mud into Lake Claron, where it settled to the lake bottom. Small organisms like snails fed in the muddy ooze, adding their calcareous skeletons to the detritus upon their death. Trace amounts of iron in the sediment would combine with oxygen and water, “rusting” many of the layers into warm red, orange, and pink hues.

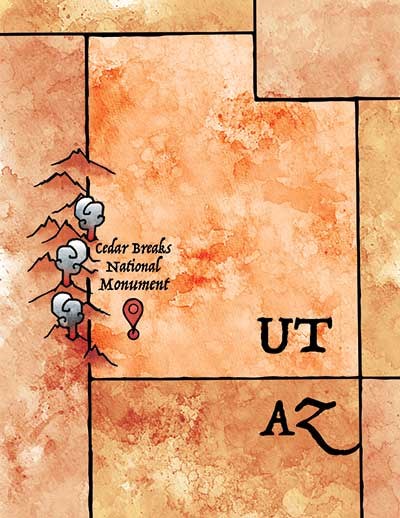

NPS Illustration by Shannon Eberhard An Explosive LandscapeA suite of volcanic rocks above the rim of the amphitheater point to the arrival of violent and turbulent times, just as the days of the tranquil Lake Claron were coming to a close about 35 million years ago.Soft grey rock near North View and on the lower slopes of Brian Head Peak belongs to the Brian Head Formation. This layer contains material erupted from volcanoes to the west near the Utah/Nevada border (more than 60 miles away) as well as sediment that settled to the bottom of the dwindling lake. These volcanic eruptions, among the largest in Earth’s history, sent pyroclastic flows (hot clouds of ash, volcanic gasses, and molten rock fragments) racing across the landscape. These flows form a volcanic rock called tuff; good examples are the Leach Canyon and Isom Formations found near the summit of Brian Head Peak.

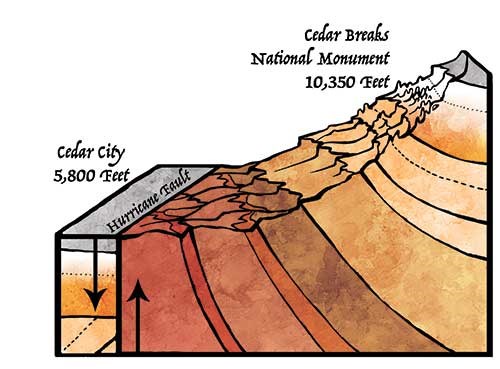

NPS Illustration by Shannon Eberhard Rocks on the RiseSome of the older rocks in the Cedar Breaks amphitheater contain oyster and gastropod fossils. Yet today the rim is more than 10,000 feet above sea level. How did this happen?Cedar Breaks sits at the boundary between the Colorado Plateau and the Basin and Range province of western Utah and Nevada. The Hurricane Fault divides the two regions in SW Utah. A fault is a fracture in the Earth’s crust along which movement occurs, creating earthquakes. For the past 10 million years, earthquakes along the Hurricane Fault have been lowering land to the west, forming the level valley far below. At the same time, the east side of the fault has moved upward, elevating Cedar Breaks and the Markagunt Plateau to their lofty heights. This process continues today. Small earthquakes are common along the Hurricane Fault. Geologic sleuth work indicates that larger quakes occur periodically. It is not a matter of if, but rather when, the Hurricane Fault will rupture again. The active fault poses a significant seismic hazard to cities and towns in southwestern Utah.

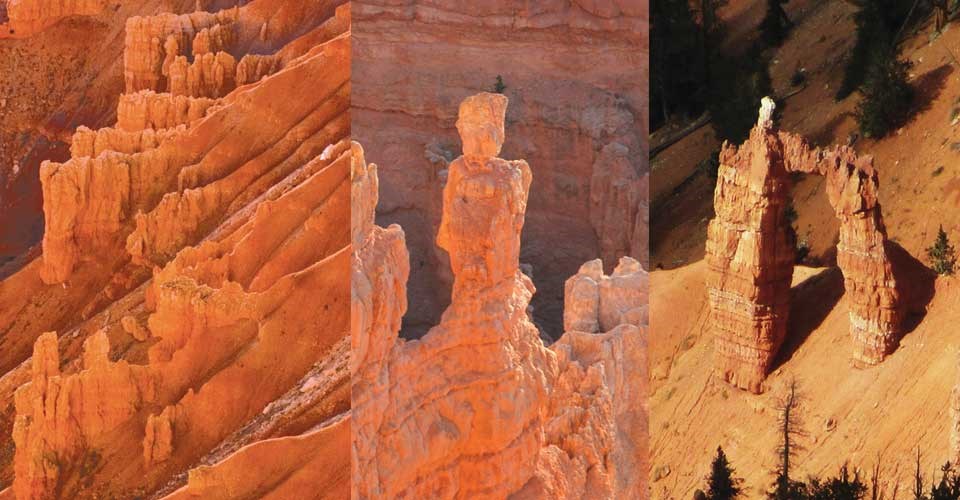

NPS Photos Finishing the MasterpieceThe rocks of Cedar Breaks may provide the canvas and palette, but a talented artist is still required to paint a masterpiece. At Cedar Breaks, the artists are weathering (the physical and chemical breakdown of rocks to produce sediment), and erosion (the transport of sediment by wind or water). Without the majestic handiwork of these fundamental geologic processes, Cedar Breaks would be a featureless alpine plateau, instead of a stunning natural wonder visited by people from around the world.While the rocks at Cedar Breaks are ancient, the landscape is still in its infancy and in a constant state of change. Prior to the uplift of the Markagunt Plateau, the rock layers of Cedar Breaks were buried deep below the surface, immune to the elements. Only after the Hurricane Fault thrust the rocks into the sky were water, ice, and gravity able to vigorously attack them and begin carving their masterpiece. Forces associated with the uplift caused the rock layers to develop fractures known as joints. Rain that falls during the Cedar Breaks summer combines with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, forming a weak acid. As this mildly acidic water seeps into the joints, it reacts with the calcium carbonate in the limestone of the Claron Formation, slowly dissolving it and enlarging the joints. When temperatures drop below freezing,as it does most nights of the year at Cedar Breaks, water trapped in the joints expands. Like a geologic crowbar, the freezing water forces the rocks apart, further enlarging the joints in a process known as frost wedging.

|

Last updated: May 5, 2025