|

Throughout the human history of Capitol Reef, women have played a role.

NPS Explorer Ellen Powell ThompsonEllen was born to a middle class family in Ohio that produced many explorers; namely her brother John Wesley Powell, the famous southwestern explorer who charted the Colorado River and more. Ellen attended Wheaton College and studied botany, later marrying cartographer and geographer Almon Thompson. In 1871, J.W. Powell asked Ellen's husband to lead a charting expedition through the only unmapped area in the lower 48 states. The trip would zig zag across the Utah - Arizona border and eventually lead the group through the Waterpocket Fold and what is now Capitol Reef National Park. Ellen joined the expedition as a botonist and was the only woman on the crew.

Pioneer WomenRena HoltRena Holt and her husband were two of the first white settlers to come to Fruita. In 1895, they were living in a boarded up tent when Rena gave birth to her first baby, a girl named Myrtle Ivy. Rena was 19 and her husband was 21 at the time. Sadly, Myrtle Ivy died from a scorpion sting at only three months old. Rena went on to have seven healthy children, many of whom lived into their 90’s. The Holts eventually built their home not too far from where the Petroglyph Panel is today. Rena worked as a midwife in the Fruita community and was known to be competent and reliable. She aided in at least 55 births without the help of a doctor. Rena would stay with the new mothers for the first ten days after the birth. She charged $10 for her services, but would often barter or accept produce in exchange for her work. Rena was also the head of Fruita’s Relief Society, the Mormon women’s aid and social organization.

Mary Jane Behunin Johnson CooperMary Jane moved to Fruita with her family as a child. She was the oldest daughter among 13 children. When she was just 17 she married Nels Johnson, a 42 year old Swedish immigrant who planted some of the first fruit trees in Fruita. A year later she gave birth to her first child, Betty Jane, who died at age 5. Mary Jane lost two more babies before having her son, Nels William. She was five months pregnant with a fifth child when her husband Nels drowned in the Fremont River during a flash flood. She gave birth to a healthy baby, Lilly May, a few months later. Mary lived in Fruita for a year and a half with her two surviving children before she met a man named Charles Cooper in Torrey and married him. They were married for eight years. Mary gave birth to three more daughters: Mary Elizabeth, Ida Pearl, and Fern May. It was complications from the birth of Fern that killed Mary at the age of 35.

Nettie Behunin NoyesMary Jane’s sister, Nettie, was one of the oldest Behunin daughters (standing on the right in the photo). As a daughter, she was expected to do household chores, although she preferred outdoor work to indoor work and was known to be strong and the best of all her siblings at repairs. She was also known to be patient with younger children. In 1890, when she was just 12 years old, she became Fruita’s first school teacher. She would teach classes outdoors to the younger children and was loved by her students. In 1896, the Fruita schoolhouse was built, and Nettie was still teaching. At some point, she attended teacher school in Monroe, UT, about 90 miles from Fruita, and earned her official teaching license. Nettie married Fred Noyes in 1897, and had their first child a year later. When she was 22, Fruita got an official Utah State curriculum and Nettie was still the teacher. Later on in life, Nettie became the postmistress of Torrey.

Thisbe Read HanksOne of the first known white women to settle in the Waterpocket Fold was Thisbe Read Hanks. She was born in England in the 1840’s. When Thisbe was 10 years old her family converted to Mormonism. Like many new converts, they decided to head west to Zion (or the territory of Utah) and emigrated from England all the way to Salt Lake City. They sold their home and their small bookstore and sailed across the Atlantic; upon arriving in the U.S. they took a train to Illinois, where they joined the Martin Handcart Company, a group of over 500 Mormon pioneers planning to make the journey west. They were pushing and pulling all of their belongings and supplies in handcarts, which were significantly cheaper than wagons with horses. Along the way, Thisbe lost her brother and was separated from her father - she, her sister, and her mother made most of the journey on their own. The company had left late in the season and encountered blizzards; hundreds of people died from exposure, starvation, and dysentery.Ephraim Hanks was part of the dramatic rescue of the Martin Handcart Company which is how he met Thisbe. He was in his 30’s, Thisbe only 11 years old. When Thisbe was 13, Ephraim expressed he was interested in marrying her. They courted for three years and were married when Thisbe was only 16 years old, becoming his third wife. For the next two decades Thisbe was constantly pregnant or nursing, raising children, cooking, gardening, cleaning, and sewing. The family stopped practicing plural marriage in the 1870’s; Ephraim divorced his other two wives and legally married Thisbe, his youngest wife. Brigham Young ordered the family to move south, in part of the colonization effort of Southern Utah. Ephraim was to set up an outpost down at Lee’s Ferry. After stopping in Central Utah to wait out the winter, they received news they were no longer needed at Lee’s Ferry. Ephraim then went south with two of the oldest boys to explore and see if there might be a suitable place for the family to settle. Ephraim and the older boys returned with stories of a majestic, tranquil place, with huge cliff walls and a pleasant creek. They would move there, to a place where no other white folks had settled. The journey was emotional for Thisbe- she was intimidated by the desert, the towering cliff walls, the true isolation and had never before seen a landscape like this one. The family settled at Pleasant Creek, where they lived in a dugout for several years before they built a house and planted fruit orchards. They named the area Floral Ranch. At this point, Thisbe was in her 30’s and had given birth to 12 children, ten of whom had survived infancy. She told Ephraim that she no longer wanted to have children, and he respected that wish. She also decided to get a horse at that time, and she would ride all over, often herding cattle. Her son said she had never felt more free. Thisbe died at Pleasant Creek in 1903.

Later ResidentsCora Oyler SmithCora was the longest resident Fruita ever had. She grew up as the youngest of three sisters, attended the Fruita Grade School and spent her free time listening to the gramophone, playing piano, riding horses, and helping her father in the orchard. Her life was marked by tragedy early on. Her older sister Clara died of typhoid at age 8. A few years later, her oldest sister Carrie’s appendix burst and she died as well, leaving Cora as her parent’s only surviving child. Cora married Merin Smith at 19. They bought land from her father and planted more orchards; Cora planted many of the trees herself. She was one of the only residents of Fruita who was against the area becoming a national monument in 1937. She foresaw how much the community might change. Cora adopted and fostered several children over the years. She had recently built a new home- with green trim and picture windows- when it was decided Highway 24 would be constructed on her land. She went to court and fought the decision, but ultimately she lost the fight to eminent domain. Her home was condemned, and the highway was built in 1962. Cora said she hadn’t wanted things to change. “I thought I would keep it like it was forever."

Elizabeth Russell Lewis Sprang KingElizabeth was an artist. She and her first husband moved to Fruita for his health. A few years after they moved to Fruita, Elizabeth’s husband died and she converted to Mormonism; within a year, she had married Dick Sprang, a widower and Batman comic book artist who was living in Fruita at the time. Elizabeth loved the red Utah rocks and was frequently inspired by them as she explored Capitol Reef, Glen Canyon, and the surrounding area. She participated in efforts to save Glen Canyon from being dammed, and wrote the book Goodbye, River in homage to the place Glen Canyon once was. Elizabeth used the landscape and history here to inspire her work. She painted and sketched landscapes (using oils, watercolors, and crayons), and created lithographs, emphasizing texture in her portrayal of cliffs and rockscapes. She also constructed large bas-relief works based on prehistoric petroglyphs and pictographs she encountered in the area. Dick Sprang said in a letter to park interpreter Davidson, that Elizabeth was “a far better and noted artist than I ever was.”

Harriette Greener KellyHarriette was married to Charles Kelly, the first park employee, custodian, and superintendent of Capitol Reef. She moved to Fruita from Salt Lake City, and remained there for 20 years. Although she was unpaid, she did a lot of the work to run the park. A family friend said: “Kelly seems to love Fruita, but his wife is beginning to get choked up about it. It seems that Kelly goes traveling around the country taking pictures, etc., and his wife is doing most of the work around the place. She practically never sees anyone to talk to, and it is pretty hard on her.” Though Harriette may have struggled with isolation and being overworked, she did become friends with some of the local women- it seems she would get together with Lila Brimhall and Cora Oyler Smith frequently.

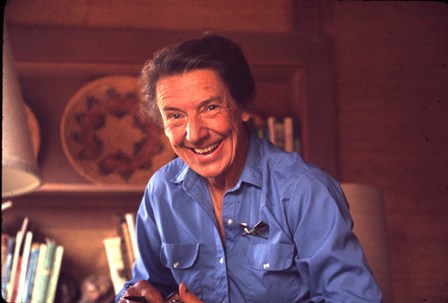

NPS photo - Charles Ellett Alice KneeAlice was working as a nurse to provide healthcare on the Navajo reservation when she met Lurton Knee, the owner of the Sleeping Rainbow Ranch at Pleasant Creek. She married Lurt in 1958, and became a partner in the Sleeping Rainbow Ranch business. She would lead tours around Pleasant Creek, the Circle Cliffs, and the southern end of the Waterpocket Fold. She was Capitol Reef’s final resident, moving to a nursing home in Arizona in the mid-nineties (when she was in her 90’s) after the death of her husband Lurt. She and Lurt had sold their property to the park in the 70’s, with the agreement that they could live out their lives in Pleasant Creek- in 1995, Alice quit-claimed her rights to the park. |

Last updated: January 19, 2022