Last updated: September 27, 2020

Article

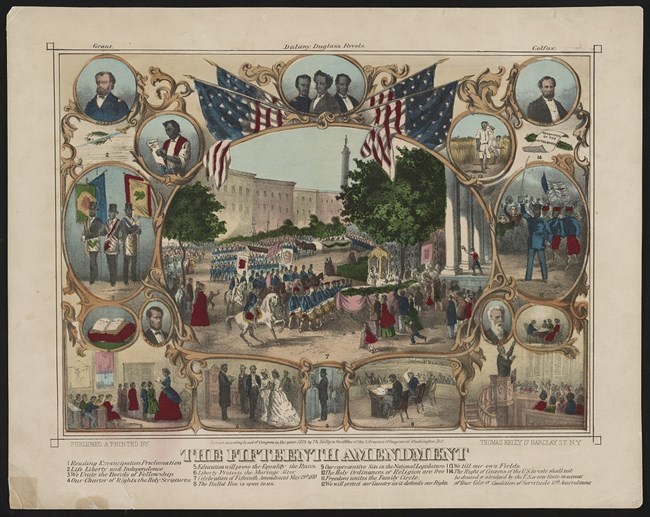

Ulysses S. Grant & the 15th Amendment

Library of Congress

Congress held numerous debates about creating some sort of constitutional amendment to achieve these ends. For moderate and radical Republicans, black suffrage was both morally right and a chance to expand their political base in the South. Civil War General and Congressman James A. Garfield argued in 1865 that “each man has a right to be heard on all matters relating to himself . . . Let us not commit ourselves to the absurd and senseless dogma that the color of the skin shall be the basis of suffrage. Let suffrage be extended to all men of proper age, regardless of color.” Numerous Northern states including Connecticut, Minnesota, and Wisconsin put black suffrage up for a popular vote during the early years of Reconstruction. There was much resistance to both women’s and African American voting rights, however. Every ballot initiative on suffrage rights in the North failed to pass (women would not get the right to vote until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920). Democratic Congressman James Brooks of New York reflected this opposition when he stated that “From the great history of the world the negro has not the capacity of self-government. Wherever the superior race has shared government with him destruction has been the lot of both.”

Ulysses S. Grant evolved in his views and gradually came to support black voting rights. He acknowledged in his Personal Memoirs that he initially supported the idea that African Americans would first experience “a time of probation, in which the ex-slaves could prepare themselves for the privileges of citizenship before the full right would be conferred.” The actions of President Andrew Johnson worried Grant, however. Grant believed that Johnson’s lenient amnesty policies towards former Confederates had emboldened them, leading to possible future conflict between the sections. “The Southerners had the most power in the executive branch, Mr. Johnson having gone to their side,” Grant argued. By 1868 it became clear to Grant that African Americans were the most loyal Southerners to the Union and in need of additional protection. By vesting black men with voting rights, it provided stability to the country moving forward. “While strongly favoring the course that would be the least humiliating the people who had been in rebellion, I had gradually worked up to the point where, with the majority of the people, I favored immediate enfranchisement [for African Americans],” Grant argued.

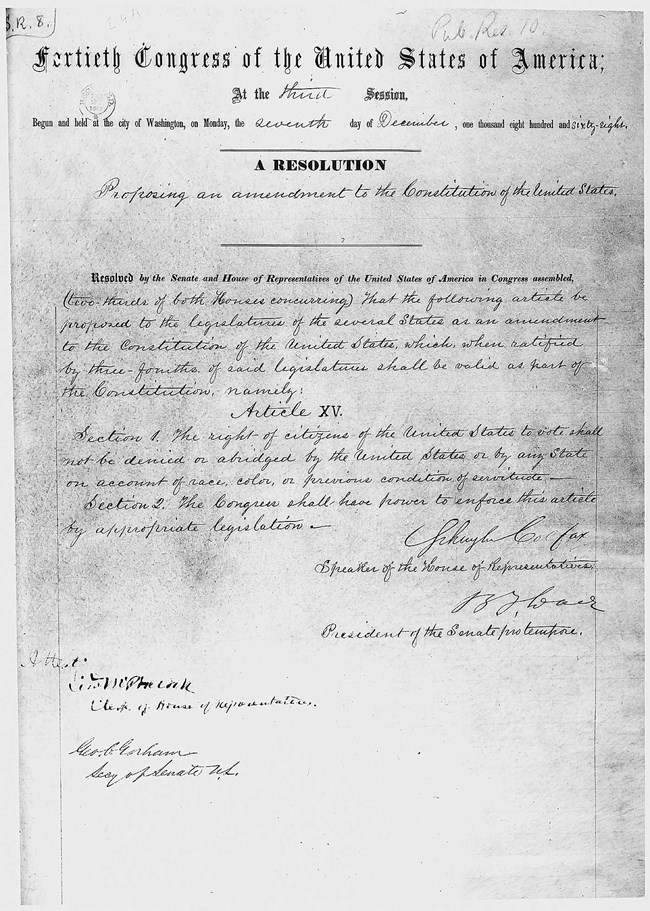

The 15th Amendment was ratified on February 3, 1870. It states that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States, or by any State, on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Below is a special message President Grant wrote to Congress on March 30, 1870 explaining his perspective on the meaning of the 15th Amendment for the future of the United States.

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

|

Special Message HAMILTON FISH, SECRETARY OF STATE OF THE UNITED STATES. To all to whom these presents may come, greeting: ARTICLE XV.

|