With the Federals facing Jackson in disarray and their left exposed, Lee sprung the trap, and the jaws began to close. Longstreet, anticipating Lee's order, unleashed his nearly 30,000 men. The long gray lines of infantry, eager to join the fight, swept forward in a furious assault.

"A regiment of cavalry, marching by twos, and sandwiched in the midst of which were Pope and McDowell with their staff officers. I never saw a more helpless-looking headquarters" General George B. McClellan

Longstreet's Assault

Library of Congress

Gen. John Bell Hood's Texans led the advance, their colors gleaming red in the evening sun. Above the thunderous roar of artillery and the noise of battle could be heard the shrill cries of the rebel yell echoing through the Groveton valley. So intense was the excitement that only with the greatest difficulty could the officers restrain their men. Moving up in support came the divisions of Generals Richard Anderson, James Kemper, and D. R. Jones.

The small Federal units were no match for the advancing Confederates. Gen. G. K. Warren's brigade was virtually destroyed by the immense Southern wave. The 5th New York Infantry ,"Duryee Zouaves", dressed in their trademark red trousers, white leggings, wide sash about the waist, short blue jackets and tassled skull caps, bought time in a brief fight. In fewer then ten minutes, the unit lost 124 men killed and 223 wounded out of 490 men present.

To make matters worse for the Federals, as the Confederate assault began, Reynolds' division had again been put in motion, ordered north of the turnpike to cover the retreat of Porter's men. The Federal left and rear was now even more vulnerable. Only a small Ohio brigade from Sigel's corps was left to hold the Chinn farm. With the collapse of Warren's line, Pope desperately began shifting reserve brigades from Sigel's corps and Ricketts' division to the high ground south of the turnpike on Benjamin Chinn's farm. A thin Union line quickly formed on Chinn Ridge. Longstreet hit it with a quick succession of blows by frontal and flanking attacks. The overwhelmed Federal lines eventually crumbled, but they successfully slowed down Longstreet's advance and bought time for Pope to establish a defensive position on Henry Hill. Finally, with sunset approaching, their energy spent and no reserves left, the victorious Southerners were forced to halt. Reynolds' Pennsylvanians and a division of regulars from Porter's corps, reinforced by regiments from Sigel's, Reno's and McDowell's commands, made a final stand on Henry Hill, poignant with memories of the First Battle of Manassas. There, with neither time nor reserves available for Lee to strike the knockout blow, the fighting ended at dark.

While the fighting still raged along the Sudley Road, J.E.B. Stuart sent Beverly Robertson's cavalry brigade eastward along the Balls Ford Road in an attempt to cut off the Federal line of retreat. As the Confederate troopers neared Bull Run they were caught by surprise by a Federal cavalry brigade under Gen. John Buford. The Federals initially repulsed Robertson's leading regiment but in the melee that followed on the grounds of the Lewis farm, Portici, Buford's men soon found themselves outnumbered and hastened across Lewis Ford. Stung by the Federals, Robertson did not press a pursuit and lost an opportunity to hinder Pope's escape. This clash proved to be the largest cavalry engagement of the war up to that point in time.

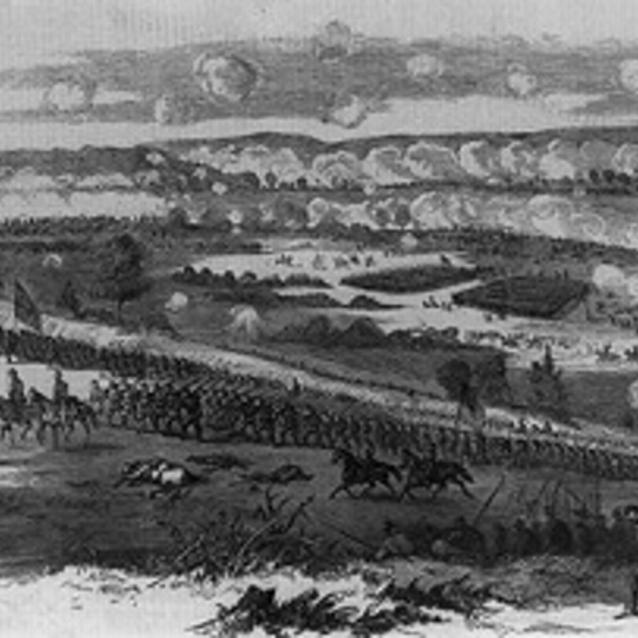

Union Retreat

Library of Congress

Union troops with poignant memories of the First Battle of Manassas the year before, assembled on Henry Hill. With courage and gallantry that matched the crisis of battle, they hurled back repeated Confederate assaults that continued until dark. The successful defense of Henry Hill made possible Pope's retreat over Bull Run to the strong defenses of the Centreville plateau.

It soon became evident, however, that a second debacle at Bull Run had occurred. The battle had cost 14,462 Union casualties. Lee had defied the odds and achieved a great victory, but the battle had been expensive for the Confederacy too: 9,474 Southerners had fallen, a loss of 17 percent.

"A regiment of cavalry, marching by twos, and sandwiched in the midst of which were Pope and McDowell with their staff officers. I never saw a more helpless-looking headquarters... Between them they are responsible for the lives of many of my best and bravest men. They have done all they could (unintentionally, I hope) to ruin and destroy the country."

-General George B. McClellan

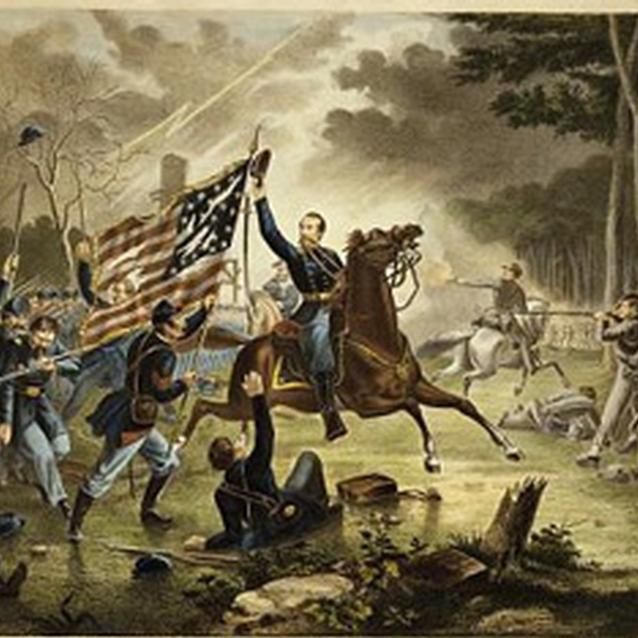

Battle of Chantilly (Ox Hill)

Library of Congress

Lee was not content to let Pope escape. Considering Pope's Centreville position as unfavorable for an attack, Lee again divided his army and sent Jackson east in an effort to turn the Federal right and cut Pope's line of retreat to Washington. Rain and mud hampered Jackson's progress and Federal cavalry detected the movement, alerting Pope to the danger. The divisions of Generals Isaac Stevens and Phil Kearny turned to check Jackson's advance as Pope began to retreat from Centreville to the fortifications surrounding Washington. A sharp fight erupted in the midst of a torrential thunderstorm late on September 1st as Stevens and Kearny intercepted Jackson near Chantilly. The outcome of the short battle was inconclusive and only added to the number of casualties. Among the dead were Generals Stevens and Kearny, a severe loss for the North. Jackson, however, was stopped and Pope resumed his retreat to Washington.

Although Lee was unable to completely destroy Pope's army in the field, its demise came shortly after its return to Washington. President Lincoln disbanded the Army of Virginia and its troops were integrated into McClellan's Army of the Potomac. This was the Union army that would be challenged with confronting Lee, just days later, when he invaded the North and began the Maryland Campaign.

Part of a series of articles titled The Vortex of Hell.

Previous: Constant Attack

Last updated: February 4, 2015