Last updated: January 23, 2025

Article

Saratoga: The Tide Turns on the Frontier (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

You are standing in an open field, shoulder to shoulder with your regiment. The British line is 50 yards away. They slowly raise their muskets and aim directly at you and your comrades. The thunder of the volley is deafening, the choking smoke stinks of sulphur. Hundreds of pieces of lead whistle as they pass over your head, by your side, and into your ranks. Men fall all around you, dead and wounded. Confusion, fear, and chaos set in. You can not understand your officers' commands in the confusion. You and the other survivors of the volley reform to return the fire to the enemy.

Out of this kind of chaos, soldiers of the Continental Army forged a victory over professional British and German soldiers near Saratoga, New York. The two battles fought here in autumn of 1777 changed the course of the American Revolution and insured the independence of the former British colonies that became the United States of America.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on materials from the archives at Saratoga National Historical Park. Saratoga: The Tide Turns on the Frontier was written by James Parillo, a former Park Ranger/Interpreter at Saratoga National Historical Park. Jean West, education consultant; Joe Craig, Park Ranger at Saratoga National Historical Park; and the Teaching with Historic Places staff edited the lesson. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history, social studies, and geography courses in units on the American Revolution or New York State history.

Time period: Late 18th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Saratoga: The Tide Turns on the Frontier relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

-

Standard 1C- The student understands the factors affecting the course of the war and contributing to American victory.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Saratoga: The Tide Turns on the Frontier relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

-

Standard C - The student explains and give examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

-

Standard E - The student articulates the implications of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding that different scholars may describes the same event or situation in different ways but must provide reasons or evidence for their views.

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

-

Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculate scale, and distinguish's other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard B - The student describes personal connections to places associated with community, nation, and world.

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard F - The student explains, actions and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among organizations.

Objectives for students

1) To describe, compare, and evaluate the strategy and fighting styles of the American and British armies during the two battles near Saratoga, New York in 1777.

2) To compare and contrast contemporary American, British, and German accounts of the battles.

3) To assess the impact of these battles on the New York frontier on world history.

4) To determine if any descendents of participants in the American Revolution live in their own community today.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) two maps showing New York State and the northern campaign;

2) three readings about the battles of Saratoga, 18th-century warfare, and contemporary soldiers' accounts of their experiences from the battle;

3) three drawings of Saratoga National Historical Park today and the battles;

4) one photo of the bluffs the Americans fortified.

Visiting the site

Saratoga National Historical Park, administered by the National Park Service, is located 30 miles north of Albany, New York, on U.S. Route 4 and NY Route 32. The visitor center is open daily except New Year's Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. The tour road is open April through November for self-guided tours of the battlefield. For more information, contact the Superintendent, Saratoga National Historical Park, 648 RT 32, Stillwater, NY 12170, or visit the park's web pages.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What do you think is happening in this drawing? What time period do you think is represented?

Setting the Stage

In 1775, British Gen. John Burgoyne identified the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor, an historic gateway between Canada and the northern colonies of British North America, as the primary target for British military operations in North America. If the British army could control it from Canada to New York City, they could cut New England off from the rest of the colonies, secure the route for supplies and reinforcements from Canada, and strengthen Indian alliances, thereby crushing the rebellion quickly and decisively.

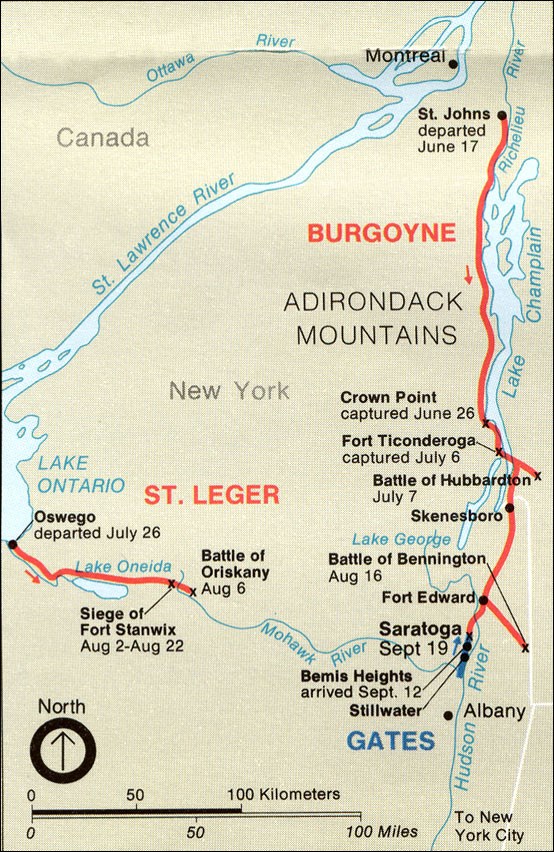

In 1777, the British planned a two-pronged attack to secure the corridor. Armies under General Burgoyne and Lt. Colonel Barry St. Leger would use the Hudson-Champlain corridor and the Mohawk Valley respectively to fall upon Albany. They would then join forces with their commander Gen. Sir William Howe in New York City, and together they would make a concerted effort to quell the rebellion. On June 17, 1777, Burgoyne led a combined force of 8,000 British, German, Loyalist, and Native American troops from St. Johns (now St. Jean), Canada into New York. Moving southward, Burgoyne took Fort Ticonderoga and brushed aside most of the American rear guard opposing him.

Then, the British plan began to run into problems. St. Leger's force moved up the Mohawk Valley and laid siege to American Fort Schuyler (Fort Stanwix) on August 3, 1777, but retreated after the Battle of Oriskany because of losses and the approach of an American relief force. Howe was at sea, preparing to attack the rebel capital of Philadelphia. He had left only a small force under the command of Sir Henry Clinton in New York City. Burgoyne's army was on its own.

Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, commander of the Northern Department of the Continental Army, led his 9,000 Americans from the mouth of the Mohawk River to a position 30 miles north of Albany, near Saratoga, overlooking the Hudson River. There they fortified Bemis Heights, where the road to Albany squeezes between hills and river. Gates' soldiers built an extensive fortified line on the heights and on the river flats. Burgoyne was forced to fight the Americans on the ground on which they had chosen to fight. At a small town in the wilderness in northern New York, farmers, merchants, and tradesmen changed the course of world history.

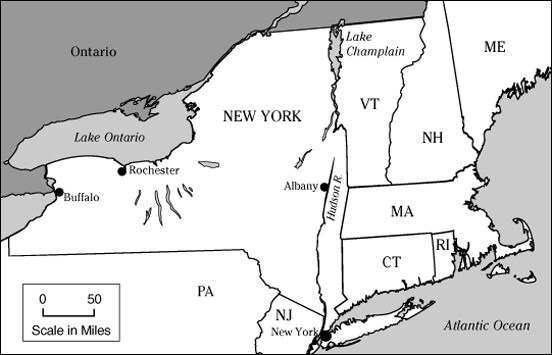

Locating the Site

Map 1: New York and surrounding region.

Map 2: Campaign for the Lake Champlain-Hudson Valley.

Questions for Maps 1 and 2

1. Locate Lake Champlain, the Hudson River, and Albany on Maps 1 and 2. Why do you think the leaders of the British Army thought it was so important to control the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor?

2. The rivers could not support the large ships needed to transport troops, only smaller supply boats. Troops marched along the rough roads that followed these waterways. Use the scale provided on Map 2 to see how far Burgoyne's soldiers traveled on foot to get to Saratoga from St. John's, Canada. According to the map, how long did it take them to reach Saratoga?

3. This area was sparsely settled at the time of the American Revolution. How might an army have maintained its supplies, including food, ammunition, clothing, and forage for the animals?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Battles of Saratoga

Burdened by his supply train, General Burgoyne's army could not hope to make a run past the American river fortifications. He was sure neither of the size nor the location of the American lines. On September 19, 1777, the British army advanced in three columns, two heading through the heavy forests on the bluffs west of the Hudson, the third, composed of German troops, following the river road. Around mid-day, Col. Daniel Morgan's corps of Virginia riflemen met the center column at Freeman's Farm. A classical European-style contest followed as British lines advanced on the two brigades of Continental soldiers and militia.

As American numbers and marksmanship began to weaken the British assault, the German column arrived. In the face of these reinforcements, the Americans withdrew. The British held the field at the end of the day but had suffered 600 casualties. The Americans had half the number of casualties and still blocked the route to Albany.

Now both armies dug in, building new fortifications and waiting. Time was against Burgoyne. Clinton was supposedly preparing to move north toward Albany from New York City, but ultimately he was not able to assist Burgoyne. While Burgoyne waited for help from Clinton, his supplies were dwindling, the morale of his men was shrinking, and winter was fast approaching. At the same time, General Gates' army grew as militia units continued to arrive. On October 6, 1777, Burgoyne and his top officers met in a council of war. Burgoyne wanted to commit more than 6,000 soldiers (all except 800 of his troops) on the next day to an attack on the American left flank. All of Burgoyne's subordinates opposed his proposal since the British lacked full knowledge of the American's fortifications and feared that an American counterattack on the weakly defended camp would leave the army without supplies or a route to retreat north. Some of Burgoyne's staff suggested that they fall back nearer to Lake Champlain while others suggested reconnoitering the American line. Burgoyne compromised and they agreed to send out 1,700 men to probe the American lines, forage for food and supplies, and decide if the hills to the west of the line could be used to mount the British cannons to bombard the Americans.

The reconnaissance force moved out around noon on October 7. Gates was informed of the movement and dispatched Col. Daniel Morgan's corps, Gen. Enoch Poor's brigade, and Brig. Gen. Ebenezer Learned's brigade to attack the right, left, and center of the British line, respectively. The Americans engaged Burgoyne's soldiers at Barber's Wheatfield and in a little over an hour inflicted more than 400 casualties, pushing the British troops back to their fortified lines. Although Poor's men failed to capture the Balcarres Redoubt (a log-and-earthen work on the Freeman Farm that was about 500 yards long and 12-14 feet high) fresh reinforcements joined Learned's brigade, and urged on by Gen. Benedict Arnold, they captured Breymann's Redoubt (a single line of breastworks about 200 yards long and 7-8 feet high). As night fell, Burgoyne's battered army retreated to the safety of the Great Redoubt (a system of fortifications designed to protect their hospital, artillery park, and supplies on the river flat).

After a day's rest, Burgoyne decided to retreat north to Ticonderoga. However, American forces had continued to swell with each passing day. Gates' army now numbered more than 12,000 and had sustained only 500 casualties in the three weeks of fighting compared to Burgoyne's 1,200 casualties. Militia from New Hampshire and Vermont cut off escape to the east side of the Hudson. Newly arrived Massachusetts militiamen who had begun to dig trenches at Saratoga (now Schuylerville) blocked the final escape route to the north. Only 9 miles into their retreat, the British army was effectively surrounded. Burgoyne and his officers concluded that they had no option left except to surrender. After negotiating over the terms, Burgoyne and his nearly 6,000 soldiers laid down their arms on October 17, 1777. According to the articles of surrender, they were free to return to England provided they promised never to fight again in America. The British troops were escorted to Cambridge, Massachusetts to await transport ships to England. However, the Continental Congress declared them full prisoners of war, so most remained as prisoners in America until the end of the war.

The Battle of Saratoga is often called the turning point of the American Revolution because the defeat of the British encouraged France to enter into a military alliance with the newly formed United States. Although the French were already supplying the Continental Army with weapons, and had been impressed by Washington's resourcefulness and favorable reports by German Johann de Kalb, they were concerned by the capture of Philadelphia. Saratoga convinced the French government that the Americans could fight against disciplined military units and win. On February 6, 1778, the French government signed accords with Benjamin Franklin and the other American envoys in Paris that recognized America's Declaration of Independence and pledged full military and financial support. Had the Americans not won at Saratoga, the French would not have supplied the troops or the French Navy that made victory at Yorktown possible. In bringing France into the war against Britain, Saratoga also brought France's allies, Spain and Holland, into the conflict. The American victory at Saratoga turned the American Revolution into a global war that Britain could not win.

Questions for Reading 1

1. How many battles were fought at Saratoga? How long a period of time passed between the battles?

2. What was General Burgoyne waiting for after the first Battle of Saratoga? How did time work against him?

3. What was the effect of the American victory at Saratoga on the course of the American Revolution?

Reading 1 was compiled from the National Park Service's visitor's guide for Saratoga National Historical Park; John Elting, The Battles of Saratoga (Monmouth Beach, New Jersey: Phillip Freneau Press, 1977); Rupert Furneaux, The Battle of Saratoga (New York: Stein and Day, 1971); and Don Higginbotham, The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies and Practice, 1763-1789 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1983).

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Eighteenth-Century Warfare

A soldier's musket, if not exceedingly ill bored, will strike the figure of a man at 80 yards; it may even at 100; but a soldier must be very unfortunate indeed who shall be wounded...at 150 yards, provided his antagonist aims at him; I do maintain...no man was ever killed at 200 yards, by a common soldier's musket by the person who aimed at him.¹

- British Col. George Hanger, 1814

Imagine you are an American soldier at Saratoga marching with your regiment. Your commander declares, "Halt!" He shouts a string of orders, "Make Ready! Present! Give...Fire!" With a crash of thunder you and the other soldiers in your line deliver a volley at the British line, only 75 yards away. The British are slightly downhill so your volley passes harmlessly over their heads. While you quickly and precisely reload for the second volley, you can hear those same orders being echoed across the field by the British commanders. They fire with the same roaring fury that so recently came from your line. Hundreds of musket balls whistle by you. The noise and smoke throw all into confusion. You see men around you falling, some dead, others crying out in their suffering. Some of the Americans try to run while others stand fast; your volley is delayed. The British volley has done what it was intended to do. As your line wavers, the British fix bayonets and charge. You are commanded to reload. Through the dense smoke you see the British line 40 yards away, closing in on you, a mass of bayonet points intent on piercing through your line. Your commander repeats the words you want to hear, the orders preparing your line to fire another volley. You fire!

The British line is shattered, the charge stops, and they retreat. You tend to the dead and wounded...and prepare. There will be more volleys and more charges until one side takes the field.

The nature of warfare in the 18th century was dictated by the characteristics of its principal weapons. Most troops used the musket, a smooth bore firearm. The inside of the gun's barrel was smooth as opposed to grooved, as in the case of a rifle. Its ammunition was a loose fitting lead ball. These two characteristics combined to make the musket very inaccurate. For example, on June 2, 1777, when Burgoyne approached Fort Ticonderoga, 3,000 American soldiers manned the outworks. As a British detachment approached the works, a lone British soldier advanced ahead of the lines. At the distance of 100 yards, the order to fire was issued to the Americans and every soldier discharged his weapon. When the smoke of the 3,000 shots cleared, two British soldiers had been wounded. The muskets had done almost no damage to the British line.²

To compensate for the musket's lack of accuracy, commanders deployed troops on open fields in lines that would halt within 100 yards of each other. Troops stood shoulder to shoulder and fired together in a "volley." By doing so they had a better chance of hitting the enemy. Speed was essential to 18th-century soldiers because the more quickly a volley could be fired, the better the chance that the enemy would break and run without returning fire. A good regiment could load, fire, and reload 3 times in a minute. Opponents would exchange volleys until one side broke and ran or until a bayonet charge ended the volleying with hand-to-hand fighting.

At Saratoga, the disciplined units of the Continental Army fought a traditional European battle. It is possible that the British broke with tradition at Saratoga, advancing in open order (one arm's length apart) rather than shoulder-to-shoulder. This formation would have made movement through the woods easier, enabling the troops to cover more ground with fewer men. However, it would also have spread the volley out, possibly reducing its effectiveness.

In addition to traditional technique, there was also skirmish fighting. Skirmishers, called "light troops," were marksmen armed with muskets or rifles. The rifle used tight-fitting balls and had a spiral groove cut in the barrel that made it very accurate over a longer distance. Because rifles took a long time to produce and were expensive, very few soldiers were armed with this weapon. Rifles had other disadvantages. A good rifleman could fire only once every 1 to 2 minutes. Furthermore, rifles could not take bayonets making them useless in hand-to-hand fighting.

Both armies used light troops. While in some instances the British made better use of them, at Saratoga the Americans used their riflemen to great effect. American marksmen aimed at gunners, keeping the British cannons quiet, and at officers of infantry, disrupting command and communications on the British lines.

Questions for Reading 2

1. What style of warfare did the American army use at Saratoga, frontier or traditional European?

2. Compare the musket to the rifle and describe the advantages and disadvantages of each.

3. Why do you think soldiers would drill and practice for hours on loading and firing muskets?

4. What were the advantages and disadvantages of open order fighting? Why might the British have adopted this technique at Saratoga?

¹ Anthony Darling, Redcoat and Brown Bess (Bloomfield, Ontario: Museum Restoration Service, 1971 ), 19.

² John Luzader, Decision on the Hudson (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1975), 20-21.

Visual Evidence

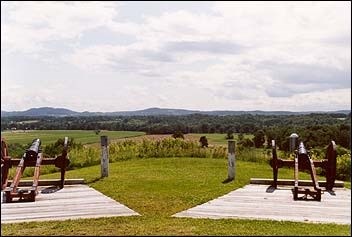

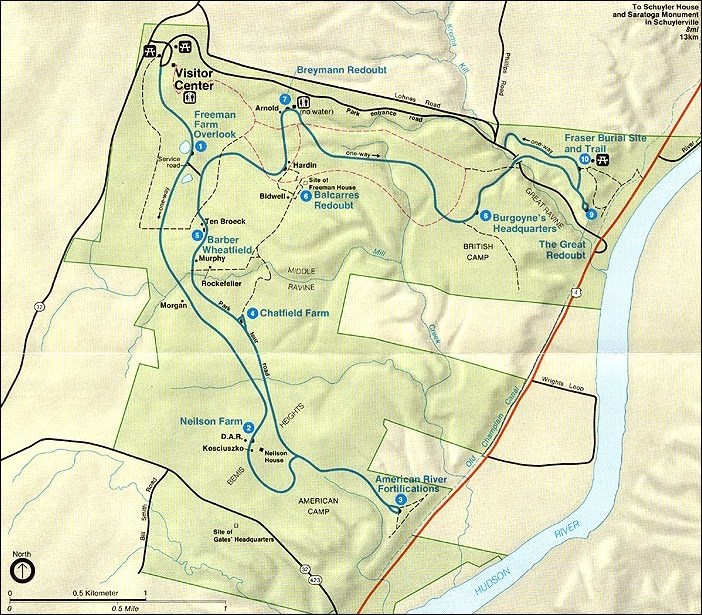

Drawing 1: Saratoga National Historical Park.

(National Park Service)

Questions for Drawing 1

1. Locate the American River Fortifications, Bemis Heights, the site of the Freeman House, and Barber Wheatfield. What role did each of these sites play in the battles?

2. Use the scale to estimate the narrowest distance between Bemis Heights and the Hudson River. Then, estimate the narrowest distance between Freeman's Farm and the Hudson River.

3. If you were the commander of the Continental Army attempting to stop the British force from reaching Albany to the south, which do you think would be a better location to fortify, Bemis Heights or Freeman's Farm?

4. Locate Burgoyne's Headquarters and the Great Ravine. Why do you think Burgoyne chose this location for his Great Redoubt and defensive line? How did the ravine add to the ability of the British to defend their position? How would this same terrain have made it a less desirable place for the Americans to place their defensive position?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Bemis Heights today.

Visual Evidence

Drawing 2: Catherine Schuyler torches a wheatfield.

(Saratoga National Historical Park)

Drawing 2 illustrates the legend that Catherine Schuyler set fire to her wheatfields along the Hudson to deny sustenance to the approaching British. Although Mrs. Schuyler never actually did this, her husband, General Philip Schuyler, did attempt to slow Burgoyne's advance down the Hudson River Valley in a number of ways.

General Schuyler, who commanded the defense of the Hudson Valley until the eve of the first battle at Saratoga, had soldiers and residents destroy or carry away food and livestock so the British would not capture it. They also destroyed bridges, blocked roads by cutting down trees, and dammed creeks to turn pathways into swampland. Delayed by these obstructions and his supply train, Burgoyne averaged only one mile a day after leaving Fort Ticonderoga.

Questions for Drawing 2

1. Study Drawing 2 carefully. How did they carry fire to the wheatfield to burn it?

2. How would destroying food supplies help the Continental Army defeat Burgoyne?

3. This drawing comes entirely from the artist's imagination. Look for people, things, actions, or behaviors that seem out of place or out of character. List your findings with a brief explanation of why they seem unreal.

4. Who are the other people accompanying Mrs. Schuyler? Provide clues to support your hypothesis. Why do you think the artist included them?

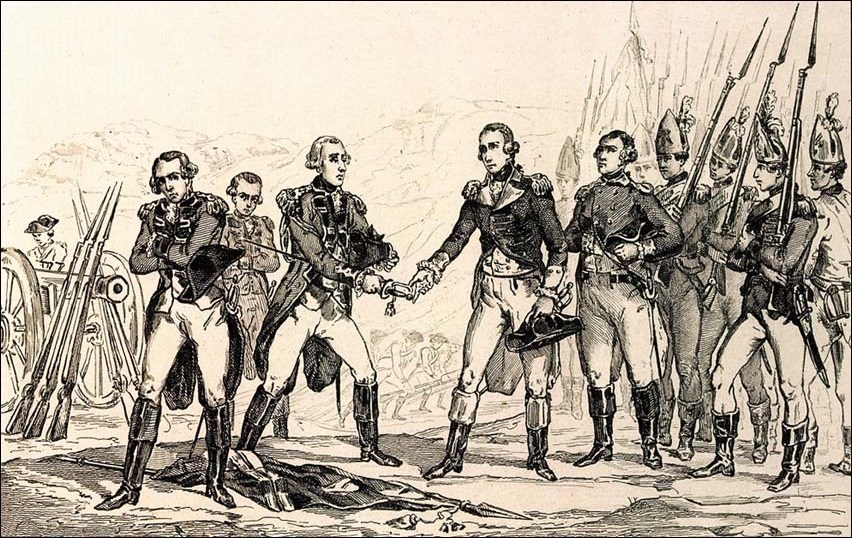

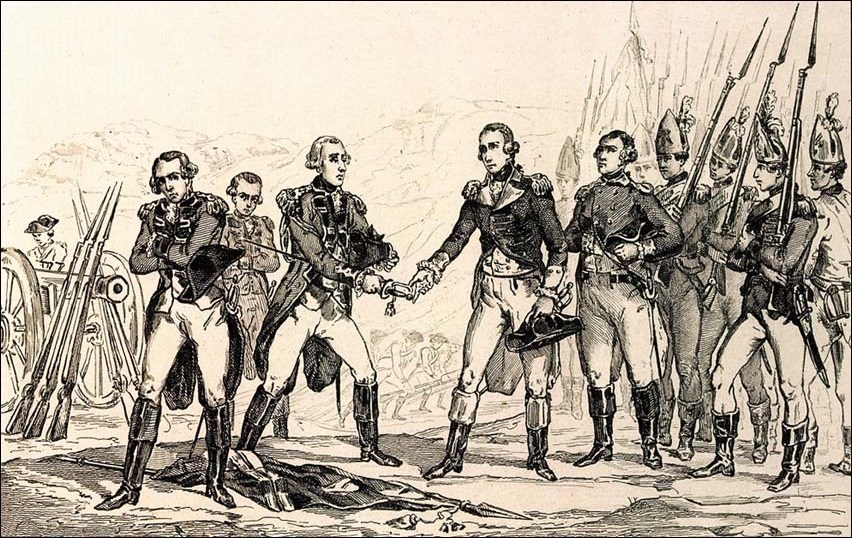

Visual Evidence

Drawing 3: Capitulation de Burgoyne à Saratoga, contemporary French engraving of Burgoyne's Surrender.

(Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

The surrender of the British forces under General Burgoyne was reported throughout Europe. France, where this image was engraved, followed the story with great interest as it weighed whether to form a military alliance with the newly declared United States of America. According to the surrender agreement, the "Articles of Convention," Burgoyne, his officers, and staff rode to Gate's headquarters between American soldiers (few uniformed) lined on either side of the road. Burgoyne's army marched out of camp with "the Honors of War" (regimental colors flying, bands playing), laid down their arms on the parade ground, then marched between the American lines. Both armies observed Burgoyne surrender his sword to Gates who immediately returned it to Burgoyne.

Questions for Drawing 3

1. What evidence is there in both the foreground and the background of the picture that this engraving depicts a surrender ceremony?

2. What appear to be the emotions of General Burgoyne and General Gates? What appear to be the emotions of the officers accompanying Burgoyne? What appear to be the emotions of the soldiers accompanying Gates?

3. What aspects of the engraving seem to be most accurate? What seem to be historical inaccuracies, and why?

Putting It All Together

Saratoga was the turning point of the American Revolution. The following activities build on material in the readings and maps and are intended to engage students with the people and events of this decisive battle.

Activity 1: A Council of War

Explain to students that before committing an 18th-century army to battle, the commanding general would hold a council of war with his staff. At Saratoga, prior to committing his troops to a second battle in October, General Burgoyne held a council of war with his top officers. Burgoyne, who was determined to reach Albany and opposed to retreat, recommended an all-out attack. His staff unanimously disagreed. Burgoyne had the option to override the advice of his council, but he compromised, agreeing to send out a reconnaissance in force of only 1,700 troops on October 7.

Explain to students that they will be assuming the roles of Burgoyne and his officers. Divide students into groups of 5 or 6 and ask each group to select a commander. Provide the students with Reading 1 and Drawing 1. Direct "staff" to examine these documents apart from their "commander." Students should evaluate Burgoyne's situation from the information he had and weigh all the options for attacking the American army, waiting for Clinton, or retreating to Fort Ticonderoga. They should consider if there are any other options and decide what option seems the most logical. They ought to review the objective of the campaign, to reach Albany, and decide if the advantages justify the risks. When both "staff" and their "commander" are ready to make recommendations, the "commander" should call the October 6 council of war. The "commander" and "staff" should make their respective recommendations. Finally, each of the group "commanders" will announce a final decision to the whole class and explain why they accepted or rejected the advice of their "staff," or how they compromised with their "staff" and why. Compare the plan of action announced by the class "commanders" with General Burgoyne's decision and its consequences. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of having a council of war and whether this 18th-century decision-making model still works today.

Activity 2: The War Continues

Remind students that it is important to remember that the battles at Saratoga occurred in 1777, but the American Revolution did not end until 1783. The alliance with France specified no separate peace, so neither party could make peace with England alone. After Yorktown in 1781, America wanted to end the war, but France had not made any gains, so America stayed in for two more years.

Ask students to research the alliance with France. They should address the following questions and present their findings in a written report.

-

Locate where French armies were fighting in 1781-1783. Could the United States supply any troops, supplies, or money to help France?

-

What British forces were still in America following Cornwallis' surrender at Yorktown? What fighting occurred in America in 1782 and 1783? Did the United States make any strategic gains during these two additional years of warfare?

-

Did France get anything out of the alliance?

-

What events in 1783 persuaded the French to join with the Americans to end the war with Britain?

-

What were the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1783?

Activity 3: Soldiers and Settlement

Explain to students that many people have ancestors who fought in the American Revolution. Some of these ancestors settled in or near the areas where they fought, while others returned to their hometowns after the war. Some moved to areas outside of the original 13 colonies and their descendants are found around the world. Ask students to conduct research in their community to determine of there are any descendants of participants in the American Revolution who live in their community. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and Sons of the American Revolution (SAR) have local chapters in many communities and each member has documented descent from a Revolutionary War participant. The national societies also keep extensive records about participants. Depending on the community, students may also be able to locate information from cemetery and church records, town or county records, or university archives and libraries. Students may wish to compile their findings on a large map with pushpins identifying the names and hometowns of the Revolutionary War participants whose local descendants they locate.

Saratoga: The Tide Turns on the Frontier--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Saratoga: The Tide Turns on the Frontier, students will learn about the battle that was a turning point of the American Revolution. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Saratoga National Historical Park

Saratoga National Historical Park is a unit of the National Park System. The park's Web pages are an excellent resource for information about this crucial battle and the battlefield today.

Fort Ticonderoga Home Page

Fort Ticonderoga National Historic Landmark provides valuable information about the "Gibraltar" of the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor, its colonial history, and the role it played in the American Revolution prior to and following Saratoga.

Lighting Freedom's Flame: American Revolution Web Page

The National Park Service maintains it own American Revolution Web page, which provides a listing of the park units with connections to the Revolutionary War and colonial America, information on special activities in the parks celebrating the 225th anniversary of the war, and a timeline of events in the pivotal year of the American Revolution, 1777.

The Yorktown Home Page

The Colonial National Historical Park administers Yorktown Battlefield. The Yorktown website has information on the siege of Yorktown, the French military contribution to victory, Cornwallis' Articles of Capitulation, and the events between Cornwallis' surrender and the Treaty of Paris.