Last updated: February 2, 2022

Article

Rebecca Turner

NPS

Rebecca Turner: From Slavery to freedom in the shadows of St. Paul’s

Born during the American Revolution, Rebecca Turner’s life in the shadows of St. Paul’s Church illustrates a local journey from slavery to freedom, the continuity of African American life in the vicinity, and the heartening story of a remarkable woman’s efforts to sustain herself and family for nearly a century.

We first encounter Rebecca in the historical record in 1806 through “The Eastchester Book of the Colored People,” giving birth to a daughter, Mary. Twenty-five at the time, Rebecca was enslaved to a local family, about 20 miles north of New York City. Six years earlier, influenced by the ideals of the American Revolution, New York passed a gradual emancipation law granting freedom to all children born to an enslaved mother upon reaching maturity (25 for girls and 28 for boys). The registration of Mary's birth to Rebecca was part of the legal requirement of maintaining a log of such children.

In 1810, Rebecca was manumitted, possibly with the assistance of Benjamin Turner, a free African American man who was her husband, but clearly corresponding with a pattern of granting freedom to the enslaved as the culmination of bondage approached in New York. The Turners took up residence on a small parcel of land at the southeastern edge of the St. Paul's property. Initially guests, the Turners within a short time erected a cabin and began to pay taxes as full landowners. They developed a farm on the banks of Eastchester Creek and raised a family. While they lived within the segregated restrictions of the Northern states in the decades before the Civil War, Ben Turner earned sufficient respect to assume responsibility for assisting the Pounder, the elected town official who impounded and held stray animals.

Rebecca eventually bore six children, -- four girls, two boys -- and employed much of her personal resources and time raising the youngsters. They attended local public schools, which operated on an integrated basis. For some time Rebecca’s children worshipped at St. Paul’s Church, and records show four of the Turners attending a segregated Sunday school in 1822. But they were not listed as congregants in 1846. Instead, the family was among the founders of a separate, nearby black Protestant church in the mid 1830s, when Rebecca was in her 50s. This development of religious independence in Eastchester paralleled the establishment of separate black houses of worship across the North in the early 1800s.

Rebecca’s important role on the farm structured her daily existence, formed by the rural rhythms of a pre-industrial time. The Turners level of agricultural production placed them on a largely subsistence level, with Ben and Rebecca managing and supervising their children in cultivating a vegetable garden, harvesting fruit trees, raising chickens and livestock and gathering salt hay from the meadow behind the St. Paul’s cemetery for their animals. In years of bountiful harvest, some of their agricultural surplus was probably sold for profit to the New York City markets through local networks. Additionally, the family would have gathered oysters and clams from the nearby creek, a practice followed by other Eastchester families.

A widow by the mid 1830s, Rebecca emerged as the property owner and responsible taxpayer of the family land, an unusual status for an African American woman in New York before the Civil War. In 1855, for instance, her property was valued at $200, a modest holding in relation to other Eastchester possessions, but fully owned and unencumbered by debt. Through necessity, she developed into the family’s chief breadwinner, supplementing her livelihood by cooking at an inn and tavern called Guion’s, around the corner from St. Paul’s, where her compensation was likely, partly remunerated through food for the family. Rebecca also took advantage of the location of her land abutting the creek to earn pay as a laundress, and an 1858 receipt, when the grandmother was 77, records payment of $7.50 for washing performed for the St. Paul’s minister William S. Coffey.

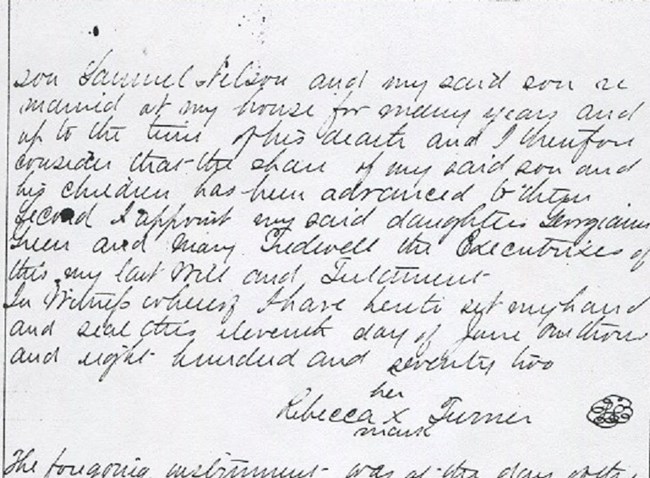

While no image or physical description has survived, Rebecca obviously had a strong, healthy constitution, living into her tenth decade, beyond life expectancy for 19th century black women. Community recollections of the Turners passed down orally and gathered years later were very positive, with an emphasis on family, which was a constant theme of Rebecca’s life. A matriarchal figure, she provided shelter at the homestead for son-in-law Samuel Nelson and his two girls, Rebecca’s granddaughters, following the death in 1860 of their mother, Rebecca’s daughter Sarah. Nelson, who may have been a runaway slave, had arrived in the area around 1830. He continued living with his mother in law through his death in 1867 at age 70, when he was buried in the St. Paul’s cemetery. Rebecca’s widowed daughter Mary -- the girl born in 1806 -- also returned to the family farm, under Rebecca’s aegis.

Rebecca died, 93 years old, on March 27, 1874; interment followed three days later in the St. Paul’s cemetery. Her intrinsic understanding of the significance of family and land was obviously imparted to her progeny, since her daughter and eventually her granddaughters, carving out a modest existence, retained the homestead into the 1930s, reflecting three generations of a family’s life in the shadows of the church.