Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Reference copy in LOT 11512.

Inspired by the first successful flights in 1903 of Wilbur and Orville Wright, of Dayton, Ohio, men such as Glenn Curtiss of Hammondsport, New York started their own aircraft companies, competing with the Wright Brothers, who had swiftly capitalized upon their success by creating the Wright Company. A California planebuilder, Glenn L. Martin, established a firm called the Glenn L. Martin Company. These outfits all did plenty of business during World War I. Following that conflict; there was little demand for new aircraft, for there were plenty of war surplus planes and engines. Martin built some of the earliest bombers--one sank a captured German battleship in a 1921 exercise, impressing military planners.

Other airplane builders also went into business: Donald Douglas, William Boeing, and Alan Loughead, who pronounced his name "Lockheed," and took to spelling his company's name that way. All three found good prospects. Donald Douglas got started by working with a wealthy enthusiast who wanted a airplane that could cross the country nonstop. By building it, Douglas gained experience that allowed him to develop a long-range Army plane, the World Cruiser. Two World Cruisers flew around the world in 1924 in a succession of short hops.

Airmail held promise. It earned federal subsidies for mail carriers that made it easy to turn a profit. A few brave travelers also began buying airplane tickets. Boeing gained an important success in 1926 with a single-engine airplane that was well suited for carrying mail and passengers over the Rocky Mountains. The same year Lockheed, which then employed the engineer Jack Northrop, crafted the Vega, which set speed and altitude records and became popular as an airliner. Jack Nothrop later founded his own plane-building firm.

Photo courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society

By the 1930s airliners were mainstays of the industry. Boeing brought out the 247, a fine twin-engine job that carried ten passengers where the Vega had room for only six. It eventually lost out in competition with the swifter Douglas DC-2, which carried 14. The DC-3, an enlarged version, entered service in 1936 with 21 seats and the range to fly nonstop from New York to Chicago. It soon swept most of its rivals from the skies. Small military orders for airplanes continued. Martin built a good twin-engine bomber, the B-10. Boeing found new business by crafting a much better bomber: the B-17. It had four engines, which gave it greater speed and allowed it to carry more gasoline for longer range. Army officials, who saw it in tests in 1935, placed orders. This gave Boeing a leg up on building bombers for use in World War II.

That war brought an enormous surge of business to the aircraft industry. Several companies built the important warplanes of the era:

Boeing: B-17, B-29 bombers

Convair: B-24 bomber

Lockheed: P-38 fighter

Curtiss: P-40 fighter, C-46 transport

Douglas: C-47, C-54 transports

North American: P-51 fighter

Republic: P-47 fighter

Most importantly, the War Department bought airplanes by the tens of thousands. Here are aircraft deliveries by year:

| Type | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | Total |

| Very Heavy Bombers | 0 | 0 | 4 | 91 | 1,147 | 2,657 | 3,899 |

| Heavy Bombers | 19 | 181 | 2,241 | 8,695 | 13,057 | 3,681 | 27,874 |

| Medium Bombers | 24 | 326 | 2,429 | 3,989 | 3,636 | 1,432 | 11,836 |

| Light Bombers | 16 | 373 | 1,153 | 2,247 | 2,276 | 1,720 | 7,785 |

| Fighters | 187 | 1,727 | 5,213 | 11,766 | 18,291 | 10,591 | 47,775 |

| Reconnaissance | 10 | 165 | 195 | 320 | 241 | 285 | 1,216 |

| Transports | 5 | 133 | 1,264 | 5,072 | 6,430 | 3,043 | 15,947 |

| Trainers | 948 | 5,585 | 11,004 | 11,246 | 4,861 | 825 | 34,469 |

| Communication/ Liaison | 0 | 233 | 2,945 | 2,463 | 1,608 | 2,020 | 9,269 |

| Total by Year | 1,209 | 8,723 | 26,448 | 45,889 | 51,547 | 26,254 | 160,070 |

Fleets of B-17s and B-24s escorted by P-47, and P-51 fighters, destroyed many of Nazi Germany's factories and railroads. B-29s carried firebombs that burned Japan's cities to the ground. The C-46 carried supplies to China. The C-47, a military version of the DC-3, carried troops as well as cargo. Over ten thousand of them entered service. General Dwight Eisenhower, the top U.S. commander, counted it as one of the items that did the most to win the war. The end of the war brought a swift collapse of the aviation industry, as the nation became awash in used aircraft.

Photo courtesy of Illinois Historic Preservation Agency

For airlines, the DC-3 remained popular for short air routes, but coast-to-coast routes along with connections that crossed the Atlantic were gaining in popularity. For these routes only new four-engine aircraft would do. Two became popular: the Lockheed Constellation and the Douglas DC-6 (along with a later and faster version, the DC-7). The rivalry between Lockheed and Douglas defined progress in commercial aviation until the coming of the jets. The first jets were military-Lockheed, Republic, and North American built the first jet fighters: the P-80, F-84, and F-86. The F-86 was the best of them, ruling the skies during the Korean War of 1950-1953.

Missiles and jet bombers also drew attention. North American made a strong and early commitment to develop a missile of intercontinental range, the Navaho. This project needed rocket engines, guidance systems, and advanced designs that called for close understanding of supersonic flight. North American brought in good scientists and developed the necessary know-how to forge ahead in this new field. Boeing showed similar leadership with jet bombers. The company used scientific data from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, supplementing it with data from its own wind tunnel, a research facility that helped to determine the best shapes for aircraft flying close to the speed of sound. This allowed the company to develop the earliest important jet bomber, the B-47. It first flew in 1947. The Air Force purchased over 2000 of them from 1948 to 1956.

The Navy and Air Force had their own requirements. Convair built the B-36, which had six and later ten engines. Boeing countered with the B-52, which mounted eight jet engines. It became the main bomber of the Air Force's Strategic Air Command. Almost every company in the industry built fighter aircraft in the 1950s, including Douglas, Grumman, Lockheed, McDonnell, North American, Northrop, Republic, and Vought. Missiles and space flight brought new opportunities. In 1954, the Air Force launched a major push toward rockets of intercontinental range, able to reach Moscow. These included the Atlas from Convair and the Titan, built by Martin. Douglas created the Thor, based in England, which had less range but was available sooner. These missiles evolved into launch vehicles for the space program.

Photo courtesy of NASA 1998, Carla Thomas GRIN DataBase Number: GPN-2000-000183

Within that program, the civilian National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) came to the forefront. During the 1960s it sponsored the Apollo program, which landed astronauts on the moon. Again there were a number of participants, including Douglas, Grumman, McDonnell, and Boeing. North American did the most, drawing on its experience with the Navaho. This company built rocket engines, a major rocket stage, as well as the spacecraft that carried Apollo's astronauts. It went on to build the Space Shuttle.

While airliner sales remained very strong, military demand fell off sharply with the end of the Cold War. Officials of the Defense Department responded by facilitating a series of mergers, to consolidate the industry within a small number of companies that would have enough business to remain strong. Boeing, holding great power due to its success in selling airliners, bought out McDonnell Douglas and Rockwell International. Lockheed merged with Convair and with Martin Marietta, forming the firm of Lockheed Martin. A similar merger created the firm of Northrop Grumman. Today, these three U.S. companies dominate the American market for commercial airliners, military aircraft, and launch vehicles for space flight.

Air Transport - Commercial Aviation - An Overview T. A. Heppenheimer

On January 1, 1914, a wealthy manufacturer named Thomas Benoist launched air service between Tampa, Florida, and nearby St. Petersburg. Those towns were separated by Tampa Bay; the only connections were by once-a-day boat or by railroad. His airline drew business all through the winter, but his prospects faded when the tourist season ended in spring. His airline shut down permanently. No one else tried to carry passengers by air for several years, and there was a reason: railroads. The United States had a quarter-million miles of track, with rail carriers offering fast, convenient service from downtown terminals.

Early airline builders therefore tried a different approach, by carrying airmail. The U.S. Post Office became involved during the Presidency of Woodrow Wilson. The planes of the day were little faster than mail trains, and aviators saw that their best hope lay in cross-country service. Flying at night, three pilots carried mail from San Francisco to New York on a trial flight in February 1921. In 1923, the assistant postmaster general, Paul Henderson, began installing powerful beacon lights to mark air routes for routine night flying in clear weather. Scheduled transcontinental air service began in mid-1924. This did not suit the railroads, which depended on income from carrying the mail. In Washington, railroad lobbyists won passage in Congress of the Kelly Act of 1925, which turned the new airlines into privately owned businesses. A follow-up law, in 1926, gave the government responsibility for aircraft safety. Collectively, these acts served to create an air transport industry that was regulated by the U.S. government and received direct subsidy through a complex set of contracts awarded to airlines to carry the mail.

Photo courtesy of Aiolos Productions, Ltd.

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh touched off an enormous surge of interest in aviation by flying nonstop from New York to Paris. Only 5,800 passengers had flown in 1926; this leaped to 417,000 four years later. In 1930, Postmaster General Walter Folger Brown set out to encourage this trend. Brown disliked the Kelly Act. He thought it provided overly generous subsidies for airmail. Brown won passage of a new law, the McNary-Watres Act, which encouraged the airlines to carry more passengers. Airmail still remained their main business, and Brown took action in that area. By law, he had the power to award airmail contracts to competing airlines. The nation's existing air-route map was a hodgepodge of local lines, whereas Brown wanted a few strong carriers that could serve the entire nation. Drawing on his legal powers, he awarded airmail routes to airlines that he favored, forced others to merge to qualify for his awards, and left still others to die for lack of business. When he had finished, he had a major north-south carrier, Eastern Airlines, along with three coast-to-coast airlines: TWA, American, and United.

Brown's reforms worked. The airlines he selected continued to dominate the nation's air routes for the next fifty years. However, Brown was a Republican. When the Democrats returned to Washington with President Franklin Roosevelt, in 1933, they lost little time in declaring that Brown's actions amounted to a scandal. He had used his powers in high-handed ways, and Democrats declared that he and the airlines together had committed fraud. Roosevelt responded by turning the airmail over to the pilots of the U. S. Army. It didn't work-they were unprepared, and a number of them crashed. Roosevelt had to rely on the airlines, whose pilots knew their business. But the Air Mail Act of 1934 cut their mail pay particularly sharply, forcing them to rely even more on passenger traffic for their income.

Photo courtesy of Miami City

This meant that they needed aircraft that could make money just by carrying people. The firm of Douglas Aircraft responded to this need with the DC-3 in 1936. It quickly drove competing airliners from the airways, and went on to dominate American aviation. As late as 1958, as jet airliners were about to enter service, the nation's airlines counted more DC-3s than any other type of airplane.

Brown left a further legacy, in the area of overseas travel. An ambitious young airline operator, Juan Trippe, convinced Brown to give him a monopoly on the right to carry airmail to foreign countries. Trippe's airline, Pan American World Airways, started with its 90-mile (145-kilometer) route in 1927 from Florida to Cuba and completed its conquest of Latin America in 1930, with 20,308 miles (32,683 kilometers) of airway in 20 Latin American countries. Profits from these Latin American routes subsidized Trippe's losses as he expanded his operations. In 1935, he introduced his four-engine Clipper flying boats on a route that crossed the Pacific, reaching from San Francisco to the Philippines. In 1939 he introduced commercial service across the Atlantic.

The air transport revolution swung into full power with the building of advanced new airplanes in the latter 1930s. Carriers expressed much interest in four-engine airliners that could carry more passengers at higher speeds, while carrying extra gasoline for longer range. Two aviation leaders competed for advantage in this field: Donald Douglas, whose firm of Douglas Aircraft was building the DC-3, and Howard Hughes.

Hughes' father had made a vast fortune in oil. Howard Hughes started his career in Hollywood, but turned to aviation, buying control of TWA. Working with Lockheed Aircraft, he crafted the Constellation airliner. Designed in 1940, it flew as fast as the fighter aircraft of the day, and could cross the nation nonstop. Donald Douglas had to match it, and did so with his own four-engine aircraft, the DC-6 and DC-7. The rivalry between these airliners and the Constellation then spearheaded the development of advanced commercial airliners until the coming of the jets.

Photo courtesy of NASA, GRIN DataBase Number: GPN-2000-000107

The first jet engines entered service with high-speed fighters late in World War II. Boeing took the lead in crafting large jet bombers: the six-engine B-47 and the eight-engine B-52. However, early jet engines gulped fuel at excessive rates, and airline executives distrusted them. Juan Trippe had different ideas. He learned that better engines were coming along, and he had enough money to order new engines that were better still. He proceeded to play Boeing against Douglas Aircraft, promising each that he would place extensive orders if either could build the long-range jetliners that he wanted. Douglas responded with the DC-8; Boeing came out with the 707. Boeing proved particularly capable at tailoring versions of the 707 that met the needs of individual carriers, and this company surged to the lead in sales.

But during 1956, as orders for the 707 and DC-8 mounted, the nation's airways were far from ready for the new jets. They needed radar and electronic aids to navigation, which were in short supply due to federal budget cuts. Then in June 1956, a DC-7 and a Super Constellation collided over the Grand Canyon, killing 128 people. This drove home the point that the air routes were unsafe even for fast propeller-driven aircraft. Congress responded, and soon the needed equipment was in place.

The new jets entered service in large numbers during the 1960s. Demand soared, leaping from 62 million passengers in 1960 to 169 million, nearly three times as many, in 1970. Juan Trippe expected that this trend would continue, as did William Allen, president of Boeing. Together they crafted an entirely new and very large commercial jetliner that was to serve this new era-the Boeing 747. However, it nearly wrecked both companies, as debt and delays plagued Boeing, followed by a national recession, which dried up demand. Boeing survived by offering new versions of earlier jets and came up with enough sales to survive. Still, it had a very close call with bankruptcy. The 747 was too large for most routes, which opened up an opportunity for an airliner of slightly smaller size. Lockheed came in with its L-1011, while McDonnell Douglas offered its DC-10. McDonnell Douglas won the competition and Lockheed stopped building airliners and became purely a military airplane builder. McDonnell Douglas stayed in the commercial world, but lacked the funds to develop anything more than variations of its DC-9 and DC-10. This raised the prospect that Boeing would hold a monopoly over the airlines. Competition eventually came from Europe.

Photo courtesy of Washington Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation

Pan Am had its own problems. By 1970 it was losing money. It nevertheless took on additional debt to purchase 747s-and found itself paying very high interest rates. The recession hurt that airline as well. It survived, at least for a while, with help from the International Air Transport Association. IATA was a cartel, which enforced a worldwide agreement that kept fares high.

For half a century, the nation's airlines had been a heavily regulated industry in which competition was more in the way of service than in fares. This regulation prevented new airlines from entering the market while stabilizing those already operating. These arrangements came to an end in 1978, as the nation entered an era of deregulation. Airline executives won new freedom to introduce cut-rate fares and to serve new routes, as well as to abandon less lucrative routes. For travelers, the consequences brought a bonanza, with passengers saving $100 billion in ticket fares during the first ten years. However, airline service was reduced, and flights to less attractive destinations were unavailable.

Some of the traditional carriers did not survive deregulation. For instance, already weak Pan Am needed new routes and new aircraft. Lacking money and credit, it declared bankruptcy and went out of business in 1991. A corporate raider, Frank Lorenzo, purchased control of Eastern Airlines. He worked vigorously to cut the pay of his employees-and soon found himself in a battle with his labor unions. When the smoke cleared, Eastern also was bankrupt.

Other airlines also fell short. Braniff Airways gambled that new aircraft would help it recover market share-only to fly into a time of high fuel prices, high interest rates, and a new recession which forced the airline to shut down. TWA was in and out of bankruptcy before finally folding in 2001, as it agreed to sell its assets to American Airlines. As the new century began, the nation counted only three strong surviving carriers: American, United, and Delta.

Photo courtesy of College Park Airport Museum

Among the airplane builders, Boeing faced an increasingly strong challenge from a European group, Airbus Industrie. Boeing and Airbus both offered airliners in a wide array of sizes and ranges to meet the needs of their customers. Boeing covered losses with profits from its 747; it has sold more than a thousand of them, at prices up to $177 million. Airbus, with close ties to the governments of Europe, has covered its own losses with subsidies. In addition, the Europeans now are building something new: the Airbus A-380, which will be the world's largest airplane, with two complete decks of seats.

In the United States, airline traffic topped 600 million passengers per year in 2001, for a fourfold increase in just 30 years. New airports could help relieve this congestion, but the nation recently has built only one large new one near Denver. Everywhere else, plans for new airports have faced stiff competition. It has also proven difficult to build new runways at existing airports although much effort is underway to expand on numerous airports around the nation.

The Government Role in Civil Aviation - An Overview--Edmund Preston, Agency Historian, Federal Aviation Administration

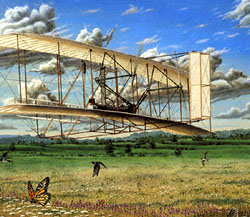

The American Government has played an important part in shaping the nation's air transportation. At the dawn of the 20th century, Langley's Smithsonian was a significant source of information for those interested in the possibility of heavier-than-air flight. The Institution distributed literature about aeronautical principals as part of its scientific mission, which was partly supported by federal taxes. Among those who studied this material were Wilbur and Orville Wright, whose own experiments led them to achieve controlled, powered flight in 1903.

Despite its early start, the United States soon lost aeronautical leadership. European enthusiasm for air power was sparked by an arms race and then by the outbreak of war in 1914. During the following year, Congress took a step toward revitalizing American aviation by establishing the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA); an organization dedicated to the science of flight. Upon entering World War I in 1917, the U.S. government mobilized the nation's economy, with results that included an expansion of the small aviation manufacturing industry. Before the end of the conflict, Congress voted funds for an innovative postal program that would serve as a model for commercial air operations.

Original painting of Gene Lehman atAir Force Institute of Technology, picture courtesy of aladdinsoft.com

With initial help from the Army, the Post Office in 1918 initiated an intercity airmail route. In 1925, new postal legislation authorized the Post Office to contract with private airlines to transport mail, which offered the hope of steady income to America's struggling air carriers. Many aviation leaders in the 1920s believed that federal regulation was necessary to give the public confidence in the safety of air transportation. Opponents of this view included those who distrusted government interference or wished to leave any such regulation to state authorities. To investigate the issue, President Calvin Coolidge appointed a board whose report favored federal safety regulation. Congress passed the Air Commerce Act of 1926, which assigned to the U.S. Department of Commerce the fundamental tasks needed for civil air safety. Among these functions were: testing and licensing pilots, issuing certificates to guarantee the airworthiness of aircraft, making and enforcing safety rules, and investigating air accidents. The Act also directed the department to take certain actions to assist the progress of aviation.

To fulfill its new aviation responsibilities, the Department of Commerce created an Aeronautics Branch. The first head of this organization was William P. MacCracken, Jr., whose approach to regulation included consultation and cooperation with industry. A major challenge facing MacCracken was to enlarge and improve the nation's air navigation system. The Aeronautics Branch took over the Post Office's task of building airway light beacons, and in 1928 introduced a new navigation aid known as the low frequency radio range. At the same time, NACA was producing benefits through a program of laboratory research begun in 1920. In 1928, for example, the organization's pioneering work with wind tunnels produced a new type of engine cowling that made aircraft more aerodynamic.

Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Aeronautics Branch cooperated with public works agencies on projects that represented an early form of federal aid to airports. In 1934 it received a new name, the Bureau of Air Commerce. In 1935 the Bureau of Air Commerce encouraged a group of airlines to establish the first three centers for providing air traffic control along the airways. In the following year, the Bureau itself took over the centers and began to expand the control system. In 1938, the Civil Aeronautics Act transferred federal responsibilities for non-military aviation from the Bureau of Air Commerce to a new, independent agency, the Civil Aeronautics Authority. The legislation also gave the authority the power to regulate airline fares and to determine the routes that air carriers would serve.

Photo from National Archives, General Records of the Department of the Navy, 1798-1947

In 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt split the authority into two agencies, the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) and the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). The CAA was responsible for air traffic control, safety programs, and airway development. The CAB was entrusted with safety rulemaking, accident investigation, and economic regulation of the airlines. Although both organizations were part of the Department of Commerce, the CAB functioned independently. After World War II began in Europe, the CAA launched a Civilian Pilot Training Program to provide the nation with more aviators. On the eve of America's entry into the conflict, the agency began to take over operation of airport control towers, a role that eventually became permanent. During the war, the CAA also greatly enlarged its en route air traffic control system. In 1944, the United States hosted a conference in Chicago that led to the establishment of the International Civil Aviation Organization and set the framework for future aviation diplomacy. In the post-war era, the application of radar to air traffic control helped controllers to keep abreast of the postwar boom in air transportation. In 1946, Congress gave the CAA the task of administering a federal-aid airport program aimed exclusively at promoting development of the nation's civil airports.

The approaching era of jet travel, and a series of midair collisions, prompted passage of the Federal Aviation Act of 1958. This legislation gave the CAA's functions to a new independent body, the Federal Aviation Agency. The act transferred safety rulemaking from CAB to the new FAA, and also gave the FAA sole responsibility for a common civil-military system of air navigation and air traffic control. The same year witnessed the birth of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), created in the wake of the Soviet launching of the first artificial satellite. NASA assumed NACA's role of aeronautical research while achieving world leadership in space technology and exploration.

In 1967, a new Department of Transportation (DOT) combined major federal responsibilities for air and surface transport. FAA's name changed to the Federal Aviation Administration as it became one of several agencies within DOT. At the same time, a new National Transportation Safety Board took over the CAB's role of investigating aviation accidents. The FAA gradually assumed additional functions. The hijacking epidemic of the 1960s had already brought the agency into the field of civil aviation security. The FAA became more involved with the environmental aspects of aviation in 1968 when it received the power to set aircraft noise standards. Legislation in 1970 gave the agency management of a new airport aid program and certain added responsibilities for airport safety.

Courtesy of Jody Cook

By the mid-1970s, the FAA had achieved a semi-automated air traffic control system using both radar and computer technology. This system required enhancement to keep pace with air traffic growth, however, especially after the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 phased out the CAB's economic regulation of the airlines. A nationwide strike by the air traffic controllers union in 1981 forced temporarily flight restrictions but failed to shut down the airspace system. During the following year, the agency unveiled a new plan for further automating its air traffic control facilities, but progress proved disappointing. In 1994, the FAA shifted to a more step-by-step approach that has provided controllers with advanced equipment.

In the 1990s, satellite technology received increased emphasis in the FAA's development programs as a means to improvements in communications, navigation, and airspace management. In 1995, the agency assumed responsibility for safety oversight of commercial space transportation, a function begun eleven years before by an office within DOT headquarters.

As the new century began, issues facing the FAA included the progress of reforms aimed at giving the agency greater flexibility. Airline accidents, although rare in statistical terms, showed the need for further safety advances. The huge volume of flights challenged the capacity of the airport system, yet demonstrated the popularity of air travel. In September 2001, however, the air transportation system was challenged by terrorist attacks in which hijacked airliners were used as missiles that killed thousands of U.S. citizens as well as many others from around the world. The government's response included legislation, enacted in November, that established a new DOT organization. This new Transportation Security Administration received broad powers to protect air travel and other transportation modes against criminal activity. Its creation was the latest step in the evolution of U.S. government's civil aviation role to meet changing needs and priorities.

General Aviation-an Overview Dr. Janet Bednarek

Perhaps the best way to define general aviation is to begin by listing what it is not. General aviation is not military aviation and it is not scheduled commercial aviation. To a great extent, all other uses of aviation in the United States fall into the category of general aviation. These uses include, but are not limited to, private and sport flying, aerial photography and surveying, cropdusting, business flying, medical evacuation, flight training, and the police and fire fighting uses of aircraft. The airplanes used in general aviation range from small, single-engine, fabric-covered aircraft to multi-million dollar business jets. They also include helicopters, restored warbirds, and homebuilt aircraft designed to use advanced composite technology.

Photo courtesy of Clipart.com

The non-military and non-commercial airline uses of aviation date back to the very early history of powered flight. Shortly after Wilbur and Orville Wright's invention came to public attention, people in the United States began to dream what the new technology would bring. Many beliefs came to make up what historian Joseph Corn called the "winged gospel." One part of the winged gospel included a vision of a future in which the airplane would be as common a form of transportation as the automobile. Another part of the winged gospel included the hope that participation in aviation would allow women and African Americans to gain greater equality in American society. Aviation never completely fulfilled that promise- many areas of aviation activity, including military flying and commercial airlines, barred women and African Americans for much of the twentieth century. However, both women and African Americans found their first opportunities to participate in flight in general aviation.

What is now known as general aviation really did not emerge fully until after the mid-1920s. Nonetheless, even before then a number of individuals began to experiment with uses of flight technology that would later become important parts of general aviation. For example, the first uses of airplanes for crop treatment, aerial surveying, and corporate flying all dated before the mid-1920s. Also, the first production and purchases of aircraft for private uses also happened very early in the history of flight. Wealthy individuals and some early exhibition pilots purchased aircraft from such pioneer aircraft manufacturers as the Wright brothers and Glenn Curtiss. Just before World War I, Clyde Cessna, a self-taught exhibition pilot, briefly operated his first aircraft company, one he founded with the purpose of building and selling small, relatively inexpensive aircraft for personnel use.

Photo courtesy of aladdinsoft.com

Cessna and those who followed him in the 1920s and early 1930s faced a number of difficulties as they tried repeatedly to build the type of aircraft that would allow for the realization of the dreams of the winged gospel. One of the biggest obstacles to affordable aircraft was the engine. The relatively affordable engines available, such as the OX-5, were so large and heavy that they demanded the design of large aircraft. Smaller, lighter engines were both very expensive and hard to get as most of the best were produced in Europe. The dream of affordable, personal aircraft would have to wait.

As aviation grew as an activity in the late 1920s, government regulations at both the state and federal levels worked to make access to flight a little more difficult. While the new programs did help give birth to the commercial airline industry, they also began to demand that pilots earn licenses and that aircraft receive certification. During the 1930s the Federal government initiated a number of programs supporters hoped would help spur general aviation. Eugene Vidal, who headed the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce, pushed for the creation of a government program to encourage the design and manufacture of a safe, affordable aircraft. Some new aircraft designs emerged from the program. Later in the 1930s, the newly established Civil Aeronautics Authority sponsored a pilot training program. This program increased the number of pilots in the United States-both men and women, and both whites and African Americans.

The late 1920s and the 1930s also witnessed the expansion of general aviation enterprises. Crop dusting, proved valuable in the South in fighting the boll weevil, soon spread throughout the United States and included the treatment of forested areas as well as the aerial seeding of rice fields. Business travel also greatly expanded, ensuring that the high-end of the general aviation aircraft manufacturing market became and remained healthy. During this time period the first affordable small aircraft-the Aeronca C-2, introduced in 1929-made its appearance. Soon thereafter American engine manufacturers, beginning with Continental, began to finally produce small affordable aircraft engines.

NASA photo, GRIN DataBase Number: GPN-2000-001800

The coming of World War II proved both a challenge and an opportunity for general aviation. During World War II most of the general aviation fleet was grounded. However, both general aviation pilots and manufacturers found ways to participate in the war effort. Pilots organized the Civil Air Patrol, an organization that eventually became an auxiliary of the Army Air Forces (and later the United State Air Force). Civil Air Patrol pilots performed a number of duties during the war, flying coastal patrol missions looking for enemy submarines, acting as fire spotters over the nation's forests, and performing humanitarian missions such as emergency medical flights and dropping supplies to areas hit hard by natural disasters.

General aviation aircraft manufacturers provided a number of products for the war effort. First, they acted as sub-contractors, using their skilled work forces to produce aircraft components for the manufacturers of military aircraft. They also sold a number of aircraft to the Army that were used in the Aerial-Observation-Post program in which Army pilots flew small aircraft in order to spot targets for Army artillery. Some general aviation manufacturers modified their small aircraft so that they could serve as training gliders for the Army Air Forces combat glider program. Given the large number of individuals trained as pilots during the war, general aviation manufacturers hoped that the time when private aircraft would come into widespread use was finally at hand. However, as events unfolded, World War II marked not the beginning but the end of any golden age for general aviation.

In the decades after World War II certain segments of general aviation continued to grow and develop. Business aviation continued and important technological changes occurred, including the introduction of turbine engines, both jets and turbo props. These high-end business aircraft remained in demand. The late 1940s also saw the introduction of helicopters, which become very important in such activities as medical evacuation and law enforcement. The biggest advancements, though, came in avionics - the radio and navigation equipment available to general aviation pilots.

In terms of personal flying, the post-war period witnessed a number of difficult times. First, the post-war boom in private aircraft purchases never materialized. Many companies, including some that had been very successful in the 1920s and 1930s, were forced out of the aircraft business. The survivors, such as Piper, Cessna and Beech, had to work hard to rebuild the personal aircraft market in the 1950s through the 1970s. They did see some successes as each company made the transition from fabric-covered to all-metal aircraft.

In the last two decades of the twentieth century, the general aviation industry, particularly in terms of personal aircraft, struggled as lawsuits against aircraft manufacturers escalated. The costs involved with these lawsuits, especially those associated with purchasing liability insurance, pushed up the price of personal aircraft. Despite Congressional efforts to help with the liability problem, the general aviation manufacturing industry still awaits recovery. Further, the number of licensed pilots in the United States peaked in 1980, and has declined since. Federal and state regulations in the late 1930s had all but made it impossible for individuals to build and fly (either from scratch or from kits) their own aircraft. In the early 1950s a group known as the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) formed to revive homebuilding. They were quite successful and though the factory production of aircraft has slowed considerably in the last twenty years, homebuilding has grown and thrived.

The four topics presented in this section give a broad overview of various aspects of America's aviation history, covering the U.S. Aircraft Industry, Air Transport-Commercial Aviation, the Government Role in Civil Aviation, and General Aviation-an Overview. These essays, slightly abridged here, can be found in full-length form at the U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission's History of Flight website in the overview of flight essay section.

Visit the National Park Service Travel American Aviation to learn more about Aviation related Historic Sites.

Last updated: August 22, 2017