Last updated: January 21, 2026

Article

Michigan Island Lighthouse

NPS

Navigating Great Water

The Ojibwe name for Lake Superior, Gichigami, translates to “Great Water,” both in terms of size and of respect.

Mariners who sail these waters continue to respect the weather of Lake Superior. Gale-force winds known as the “Witches of November” blowing in excess of 100 miles per hour can develop into storms strong enough to produce tornadoes as far away as Virginia.

Great Lakes mariners faced a plethora of reasons their ships might sink to the bottom of the lake. As commerce and passenger service increased on Lake Superior, ship captains were required to keep one eye on the weather while maintaining a sharp lookout for ships that passed too closely. They knew nautical maps could be inaccurate and fail to indicate the presence of shallow water shoals which caused them to run aground.

Ship captains were also aware of the ever-present possibility that a minor mechanical issue could quickly transform into something much worse. Every mile traveled on Lake Superior’s surface required intense focus and high levels of meteorological awareness from the sailors, and maps and compasses were sometimes not enough to ensure safe passage from one port to another. Even on the calmest of days, it was not uncommon to greet the sunrise with calm skies and light winds, only to be praying for one’s life by nightfall.

Theodore Karamanski, author of Great Lakes Navigation and Navigational Aids Historical Context Study, wrote “Nothing better symbolizes the drama of American history than a lighthouse on a storm-washed shore.”[1] Karamanski describes the vital and irreplaceable role that lighthouses have played in American history. By 2013, more than 400 lighthouses stood upon the international shores of the five Great Lakes with more than 262 structures located on the American side.

From the earliest days of Great Lakes shipping to the present, sailors of all skill levels have had to be concerned with delivering cargo and passengers safely from one port to another across the big lake. Before the advent of lighthouses, mariners sailing Lake Superior’s waters relied on simple, crudely drawn maps or simple celestial navigation as a means of conducting a safe journey from one port to another. Soon after the War of 1812, when competition for the fur trade intensified between French, British, and American traders, ships ranging in size from two-masted schooners to large, fast-sailing sloops plied the waters of Lake Superior.

By the mid-1800s, huge “lake freighters” carrying several tons of goods and numerous passengers added to the increasingly-crowded flow of traffic on the lake. While ship captains felt confident in their ability to steer clear of other ships, they knew the one element they could not control was the weather. For that, they needed assistance of land-based navigational aids that would guide them through the darkest nights and the worst cases of inclement weather.

NPS

The Lighthouse Act of 1789 provided government funds for the construction of lighthouses at numerous locations nationwide. By 1843, five towers illuminated Lake Superior waters, with the number of lighthouses increasing to 34 by the end of the decade. Ships heavily-laden with iron ore had to skirt the rocky shoals of the Apostle Islands on their way from ports like Ashland and Superior Point before heading into the deeper waters of Lake Superior. It was still possible, however, that ships would encounter bad weather despite the number of lighthouses lining the lake’s coast. Ships continued to strand on shoals of founder in heavy seas, some sinking to the bottom with passengers, crews, and cargoes still aboard.

“Storms were the greatest threat to shipping. The power of the wind and waves magnified exponentially the dangers imposed by navigating on [Lake Superior.] In fair weather, a schooner or steamer could manage without harbors of refuge, make port without the aid of pier lights and even overcome grounding on hidden shoals. In heavy seas, these issues became lethal.”[2] No single season was favored over the other, although the winter months usually produced the most severe weather conditions. From late spring to early fall, shores quickly became shrouded in blinding mist and fog.

Michigan Island Light Station

In 1852, Congress approved legislation to provide the money to add to the number of lighthouses located around Lake Superior by appropriating the funds to construct light towers in the Apostle Islands and Isle Royale region. Work crews built the first lighthouse on Michigan Island in 1856. Located on an isolated island seventeen miles northeast of Bayfield, Wisconsin, the island was only accessible by boat and seemed to be the ideal site for a navigational aid that could pierce the thick fog and dark nights. It was also located far enough away from the coast to not be confused with other sources of light coming from the shoreline.

NPS

Building the Michigan Island lighthouse was not an easy task. Construction crews ferried the stone for the structure from a quarry located ten miles away. As long as the weather remained agreeable, heavy barges delivered several tons of stone to the island each day. Stonemasons sculpted the rocks to conform to the tapered shape dictated by the Lighthouse Board. Once a certain height was reached, the newly formed wall was covered with a special concoction known as “Roman Cement,” a natural adhesive formed by mixing clay deposits with sand which hardened quickly and allowed crews to continue their work without lengthy delays.

Each lighthouse was equipped with six windows and twelve rectangular-shaped glass lights measuring eight inches by ten inches. Copper poles were attached to the top of each lighthouse to redirect the energy of a lightning strike downward and away from the structure. This addition to lighthouse safety proved its worth when the Michigan Island lighthouse suffered a lightning strike in 1889 that resulted in a moderate level of damage but prevented the building from being completely destroyed by the devastating power of the lightning bolt. By the end of its construction, the Michigan Island stood fifty-two feet in height. A 3.5 order Fresnel lens manufactured by the prestigious Henri Lapaute Company of Paris, France was installed in the tower and a keeper was hired to run the station. Final costs on the construction topped out at more than $12,000 ($341,761 in 2019 values) and exceeded initial construction estimates by approximately $7,600.

Historic American Buildings Survey, Survey HABS WI-317. Library of Congress.

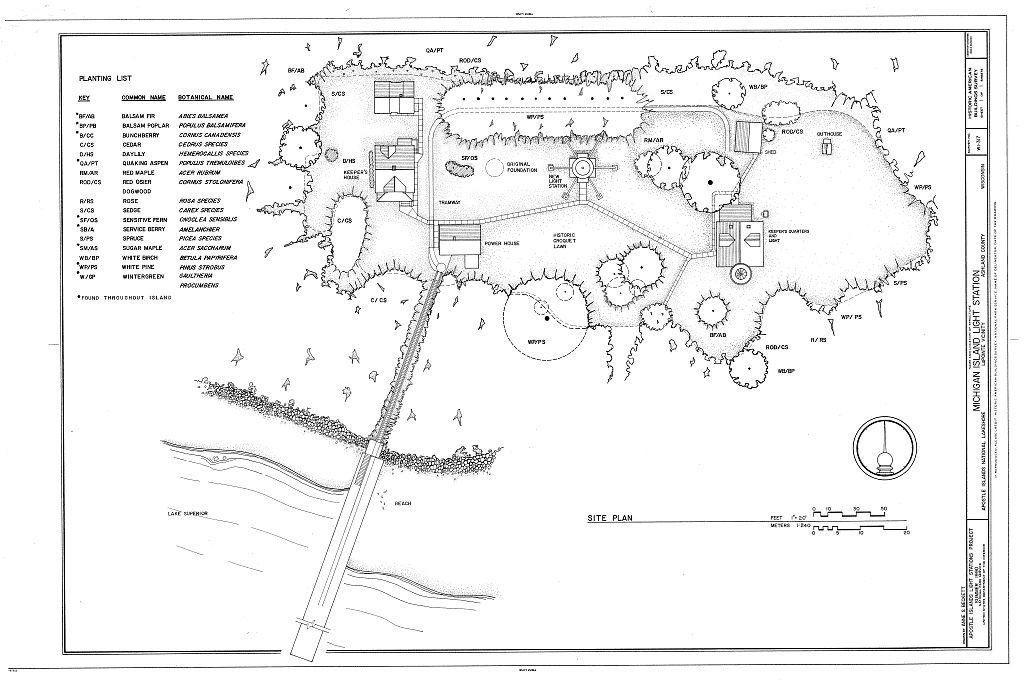

The landscape of the light station was shaped both by utilitarian needs and to provide pleasure for the occupants. A network of paths connected several buildings, and the open turf area was inturrupted by trees that offered shade and wind protection. The grounds included a historic croquet lawn and some ornamental plantings of rose and day-lily.

NPS

The tramway and tram tracks, built in 1928, changed both the physical organization of the landscape and the way in which the light station operated. The construction of the tramway reoriented the main pedestrian route from the water's edge to the new Keepers Quarters, rather than to the Old Michigan Island Lighthouse. This construction of this transportation system brought a new technology to the light station and allowed a much more efficient movement of goods and fuel up the bank and around the light station grounds.

The first Michigan Island lighthouse lived a short life. Its lamp was extinguished after approximately one year of service, and operations were brought to a halt in 1858. The valuable Fresnel lens was removed and sent to the La Pointe lighthouse on nearby Long Island, and the stone tower stood empty for a decade.

The island would reassume a vital role in Great Lakes’ shipping when an upsurge in the number of vessels sailing in and out of the port of Ashland renewed the need for a light on Michigan Island to guide vessels into the western approaches of the Apostles. In 1868, the island’s lighthouse was reopened and renovated, and after being refitted with a new Fresnel lens, the tower once again cast its beacon across the lake on September 16, 1869. For the next thirty-nine years, the lighthouse on the tiny island continued to provide effective – and welcomed – navigational aid to ships sailing upon Lake Superior.

Matters changed, however, in 1908, when it became clear that ships passing north of Michigan Island were unable to detect the lighthouse’s beacon. Although the lighthouse was located atop a high bluff, it was screened from ships travelling into the islands from the northeast, which prevented ship captains from seeing the beacon at this critical angle. Embarking on a twenty-year fundraising venture, the Lighthouse Board sought to raise the funds to erect a replacement lighthouse on a higher elevation. When political events in Europe forced the world into war, all monies designated for lighthouse repair were put on hold.

NPS

Rather than erect a replacement tower, the Lighthouse Board repurposed a cast iron, 112-foot skeletal tower which had been lying upon the banks of the Delaware River and installed the tower atop the island’s highest geographical point. The Fresnel lens was removed from the original lighthouse and, with the assistance of an electric-powered, 24,000 candlepower lamp, the new beacon from Michigan Island was not only more visible, but also extended at least twenty-two miles across the lake.

The use of electricity to power the lighthouse lamp meant less staff members were needed to operate the station. Between 1929 and 1937, most first- and second-assistants worked a period of one year or less before resigning or transferring to another station. By 1939, the station was redesignated as a one-person assignment: Robert Westveld was left to run Michigan Island by himself without the assistance of first- or second-assistants. In 1943, Westveld too was relieved when operation of the lamp became fully automated. Coast Guardsmen stationed on nearby Devils Island took over the responsibility of running the station and made periodic visits to the island to ensure its continued operation. The original Fresnel Lens was removed and placed on display at the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Visitor Center in Bayfield, Wisconsin. To ensure uninterrupted safety for ships passing Michigan Island, the light tower was equipped with a modern DCB-224 aerobeacon lens, which was capable of projecting its beam beyond the twenty-two mile limit of the previous Fresnel lens.

Between 1939 and 2019, Michigan Island sat almost forgotten. Between 1962 and 1970, only one resident, Donald Bliss, lived on the island. Logging operations on the island continued until 1968, and other than the occasional maintenance-related visit by the Coast Guard, Michigan Island remained largely unoccupied until 1970, when the National Park Service created the Apostle Island National Lakeshore and included the site in the group of islands. Today, the island is a contributing property of the Apostle Islands Lighthouses, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. The Michigan Island Lighthouse is also documented in the Library of Congress under Historic American Buildings Survey WI-317 (A-C).

From 1970 and through today, the NPS has worked diligently to ensure visitors to Michigan Island can experience the island’s rich history. Improvements to the station’s grounds and buildings ensure visitor safety while providing the opportunity to imagine the isolated life of a lighthouse keeper and their family. Through the efforts by the National Park Service, Michigan Island’s unique place in Great Lakes shipping, the light station landscape, and the people who lived there have not been forgotten.