Part of a series of articles titled Maud Malone - New York City Librarian and Suffrage Powerhouse.

Article

Maud Malone: The New York City Suffrage Parade of 1908

https://www.loc.gov/item/2014680145/

With more and more women deciding to participate in open-air meetings, Maud Malone decided to hold a parade in February 1908. Maud was always willing to be brave enough to go first. Again she invited women club members to join her:

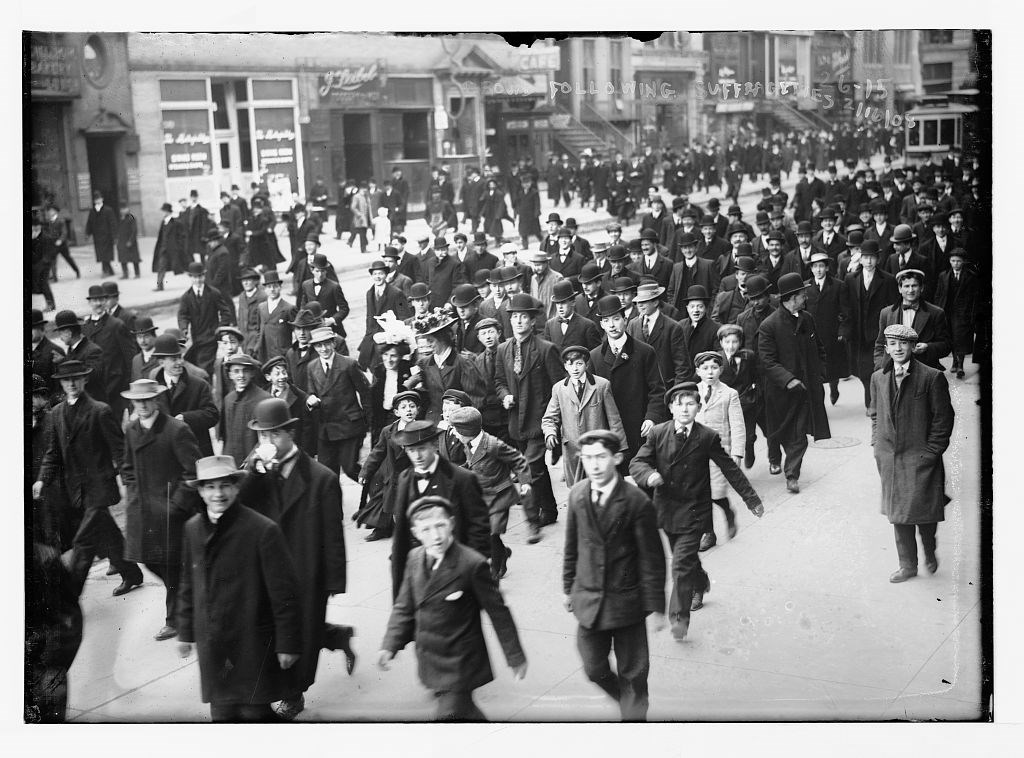

Again most women's club members across the city were repelled by this idea. Suffrage leaders such as Carrie Chapman Catt spoke out strongly against Maud’s methods and how much it would harm the suffrage movement.[2] The police tried to ban the parade, stating that only funerals received permits for gatherings on Sundays. But just as with the open air meetings, the parade on February 16, 1908 was a huge success.[3] Maud and about thirty women from a variety of suffrage groups joined with about two thousand men, defying the police ban. The throng walked together on a Sunday afternoon stroll from Union Square up Broadway to a meeting hall on 23rd Street. There were no arrests and a good time was had by all.[4]“Dear Madam: As you will probably have seen from notices in the public press, it is proposed to hold shortly in New York a demonstration and parade of women in order to protest against the present unequal political and economic position of women and the arbitrary legislation to which they are subjected… It is proposed to organize the parade on the broadest basis possible and to invite the cooperation of women of all parties and public bodies, so that it shall be truly representative.”[1]

The press loved the suffragette parade and their positive reviews were reprinted in papers across the country. “Great Moral Victory, but without Parade” beamed the New York Tribune. The Washington Times wrote: ”Amazons Bluff New York Police: fair Suffragettes take ‘quiet walk’ up Broadway while Police admire.” The New York Times reported "Suffragist Parade Despite the Police: They went to the rallying point and the police said, “Move on” They did.”[5]

The fact that so many thousands of men participated in the suffrage parade was confirmation to Maud that her efforts to build a community of men and women interested in collaboration were working.[6] Street meetings, speeches, spontaneous debates and discussions were combining to create a political and social coalition of progressive men and women. She would write of the parade:

One of Maud’s innovations was to make the American version of Suffragette activism fun.[8] While English women used whips and chains to shock the British citizens into realizing the seriousness of their cause, Maud realized that to engage the American public into accepting an American Suffragette spectacle, it would have be enjoyable. Photographers and newspaper reporters captured the smiles and fun Maud brought to the February march. Journalists often contrasted the violence of English rallies with the lighthearted cooperation in Maud’s first parade.[9] Reporters loved to include in their news articles the humorous and joyful but serious banter between Maud and her male audience.[10] Suffragette activism and the spectacles suffragettes created made Americans form an opinion and feel an emotional response to feminism, equal pay and voting rights. Those emotions often led to a call for action. Those political actions, open air meetings, marches, canvassing for votes, petitions and protests enabled just enough voting men to reconsider how they felt about votes for women and equal rights. Those changed minds brought enough state legislative votes to enact the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1920.“There were as many men as women who took part that day in our demonstration. They walked up Broadway with us to 23rd street and then went inside and spoke for us at our indoor meeting held in the Manhattan Trade School. I myself could tell you of a great number of men of all shades of radical opinion…who marched with us that day. It only seems right that whenever possible I should speak up and defend the men, even from well-meaning critics. Indeed, from the beginning of the militant movement here men have always been our best backers…”[7]

Maud was not afraid to correct those who followed in her path when she felt they strayed. She quit the suffrage organization she herself had founded, the Progressive Women’s Suffrage Union, saying, ”The present policy of the Union is: First to attract a well-dressed crowd, not the rabble… It also seeks to exclude from its platform men and women who announce they are Socialists……To me the movement to be truly progressive should recognize no prejudice of race, color, difference in clothes or creed, whether religious, or economic…” Maud felt that the group had lost her original vision of accepting everyone. She believed as her physician father had before her, that democratic movements should include all people. “It was in the broadest spirit of democracy that we went out into the streets inviting all passersby to listen to our arguments and offer their objections or ask questions.” She wrote. [11]

By 1909, less than two years later, conservative suffragists as well as militant suffragettes across the US would adopt massive street parades and open air speaking to get their message out to the public.[12] They quickly forgot[13] about the time when they denounced open air speaking and suffrage marches as bizarre and degrading.[14] Suffragists and suffragettes also quickly forgot about that “pushy” woman who showed them something they did not expect to see: how open air speaking and marches done with a dash of joy and humor, could reinvigorate a dying movement.[15]

Notes:

“Suffragists compared with Suffragettes: Latter are of the militant type whose methods are opposed by Brooklyn Women” Brooklyn Daily Eagle February 2, 1908.

[13] “Names of Suffrage Pioneers Not Forgotten” The Sun [New York] December 9, 1917. Ironically, in an attempt to remember women who helped win the right to vote in New York State in 1917, Eleanor Booth Simmons gets most of her facts wrong and largely ignores Maud Malone: “The suffrage movement in New York as I knew it is compassed between two street meetings: one, the very first one ever held here, on the southeast corner of Madison Square, on a cold windy morning in March 1909-or perhaps it was 1908; the other in Abingdon Square on the eve of election day November 5, 1917…That very first street meeting ws organized, I believe by Mrs. Borrmann Wells of England…by Mrs. Wells and Mrs. Sophia Loebinger, a plump temperamental, energetic, voluble little women from somewhere in Harlem, and Miss Helen Murphy a tall, dignified gray haired woman…I believe Maud Malone was with them, but Maud was quite mild then…”

Last updated: July 5, 2019