Part of a series of articles titled Maud Malone - New York City Librarian and Suffrage Powerhouse.

Article

Maud Malone: Epilogue and Legacy

https://www.loc.gov/item/2014700130/

And what became of Maud? After 1908, Maud continued to push the boundaries of public opinion on gender roles and political tactics. At public meetings, on the street and even in restaurants, Maud would wear a fabric sandwich board-like sign running from shoulder to waist, demanding votes for women. Journalists nationwide continually ridiculed her for her insistence on wearing the sign and equating herself with down-and-out “sandwich board men.”[1] Maud was mocked for insisting on her right as an American to interrupt candidates during speeches, to politely but firmly ask for their view on votes for women.[2] American men, she said frequently interrupted candidates with questions, and an American woman should have the right to do the same. For pioneering this right, she was frequently and violently removed from meetings by the police after candidates for president, governor and New York City mayor all refused to answer her questions.[3]

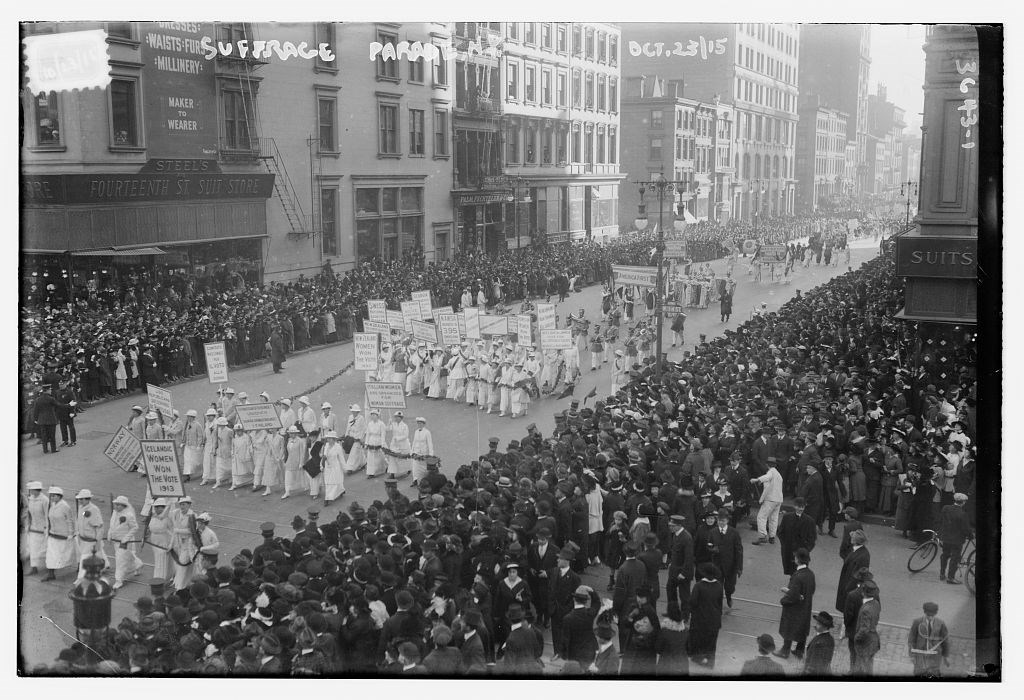

Between 1909 and 1917, after a myriad of street meetings, parades, and legislative petitions still had not brought women suffrage, Maud engaged in other forms of non-violent protest, and was arrested and jailed for her actions. She followed the arrests up with letters to the editor and interviews explaining that she was not a publicity seeker.[4] Maud carefully explained the reasons why the women’s suffrage movement needed to now adopt more aggressive tactics, similar the more violent tactics of women in England.[5] “Nobody can be on the fence in such a question as the suffrage. Everyone must have convictions of some kind or other – possibly without knowing it. They don’t realize they have convictions until they are hit. The punch administered by militancy will send them to one side of the fence, into the camp where they belong. Then we shall know where we stand.” [6] She also stated,

In another interview she spoke of her larger goal: “In our fight American Militants have been inspired by the fine fight the English women are putting up. Their fight is ours. This is in accord with the spirit of the times, which would break down all barriers of race and class, of sex and color, and join us in a common sisterhood.”[8]“All governments have great respect for property but they have no respect for human life. It is not wholly the vote that women are fighting for but to improve their moral, social and economic conditions. We are going to have a very militant movement here in America. We can already see things shaping that way. The street meetings, the hikes, the parades are all militant, only more mildly so than in England. If we are halted here the mildness will fade and something more desperate will take place…So far as American women are concerned, they’ll get their rights sooner or later. It’s only a question of how thick our men’s heads are. If an appeal in their sense of justice prevails we may get our liberties without force. If not, there may be broken heads here too.” [7]

For many Americans, her actions and beliefs had now become too far outside of what was acceptable female behavior and she was ridiculed in newspapers in New York and across the country. [9] Yet in a few years’ time suffrage leaders Alice Paul and fellow Brooklynite, Lucy Burns adopted non-violent protests. Maud joined their protest, arrest and imprisonment in a Virginia jail.[10] Many historians today believe that these militant tactics along with the coalition building done by less militant Suffragists combined to provide the necessary ingredients winning the constitutional right to vote in 1920.[11]

Maud Malone an innovator, an agent of change was one of those people who started new things and then compelled others, resistant and complaining, out of their comfort zone, to follow her path. For those who fearfully followed Maud, it was perhaps best to forget those uncomfortable times when she introduced them to her methods. Maud also continually broke with society’s idea of womanly behavior. Politically she became a library Union leader and moved from being a Progressive Republican to a Socialist.[12] In the 1930’s after her politically motivated firing as a New York City librarian, she became a Communist managing the Daily Worker newspaper’s library.[13] True to form, she frequently challenged the American Communist Party for their sexist oppression of women. [14]

Because of Maud’s politics and her bold ways, when it came time to write the history of women suffrage in the early 1920’s, Maud Malone and her innovations were largely left out.[15] The newspaper articles that chronicled her exploits and captured her quotes, were bundled and tied up in string, stored away and forgotten until the present digital age.

That is a shame because what Maud did, and how she did it could possibly serve as a lesson today for anyone who wants to reenergize a movement that has lost the will to move forward. Maud is one of the few white middle class suffragists of her day who tried to steer the movement away from racial and class prejudice. Today, how do we notice the prejudices afflicting ourselves and our peers and work within our community to end them? Maud also took notice the persuasive power of street preaching and parades, both effective tools developed by the Salvation Army and Socialist organizers. She adopted their methods to reenergize the suffrage movement. How do we have eyes to notice innovations that could improve public discourse in our own time? Are we willing to do as Maud did, and press on doing the right thing, even if no one listens?

Maud did not want to go away quietly. When newspapers interviewed suffragettes and suffragists about the exciting developments that had just occurred during 1908, they left out any mention of Maud Malone. In response she wrote the following letter to The New York Times:

To the Editor of The New York Times:

In your enumeration of the various suffragette organizations in New York City you mentioned several…each of which is working for woman suffrage independently of one another. I would like to add the name of one other suffragette organization, the Harlem Equal Rights League, a woman suffrage league composed of radical working men and women, which for the past four years has carried on a vigorous campaign not only in Harlem but all over the city.

The Harlem Equal Rights League was the organization which started the suffragette movement in the United States.

Maud Malone, President, New York, Dec. 28, 1908[16]

“How Suffrage Battle was waged at Albany” Brooklyn Daily Eagle February 25, 1909. “All during the afternoon there was that feeling evident in the atmosphere that something was going to happen- something dramatic and thrilling. The sandwich suffragette, who proved to be Miss Maud Malone…wandered around lonesomely through the assembly hall as if she would have stirred up a demonstration of some kind, but she received no encouragement. There was even a rumor that she tried to get the suffragists to march to the capitol in a body with banners aloft reading, “Votes for Women,” but they would not. They conducted their campaign quietly and with dignity."

"Women in Albany in Ballot Battle: Suffragettes, Suffragists and Antis Argue for Hours Before the Lawmakers” The New York Times February 25, 1909. “Maude Malone has recently become an independent worker, parading alone on the street, and wearing a big yellow Suffrage banner, braved the antis in their lunchroom at Albany yesterday, her yellow “votes for women’ buttons shining and yellow banner flying. “I challenge any one here to give a reason why women should not vote,” she said. There was dead silence for a moment, and then an ice voice exclaimed: “you are the best argument against woman suffrage I have ever seen." Miss Malone melted away, but only to appear later undaunted in the Assembly chamber, where she was again suppressed by a cheerful, competent, but persistent Sergeant at Arms.”

[2] “Maud Malone” The New York Press January 11, 1913. “I saw an odd item lately about Maud Malone how, when there’s anything particular on foot, she pins a great big yellow suffrage banner across her breast and marches through the streets. Why doesn’t she put one on her back as well? Be a sandwich man! A sandwich woman! And advertise the cause of woman suffrage both before and after! She’s said to be a nice, harmless little lady; Maud Malone only with a very large and buzzing bee in her bonnet. She just must interrupt meetings. She just must ask everbody who gets up to make a speech what he intends to do for woman suffrage. None of the leaders in the suffrage movement approve her course. None of them thinks it does any good. But that doesn’t daunt Maud Malone…”

[5] “A Plea for Militancy: Miss Malone Calls Upon Suffragists to ‘Fight Back’" New York Tribune March 8, 1913 p.8. “Tyranny never allows itself to be attacked without fighting back. It is militant. While we were suffragists we were harmless. As soon as we became suffragettes all the corrupt forces both in high and low places attacked up. Their first open attack on militants was when I organized the first suffrage parade in the United States in 1908. The police acting for these forces tried to break up our parade. But we went ahead and marched in spite of them, five thousand men and women marching with us….”

[7] “Justifies their Methods: What Maud Malone says of the Suffrage War in England” The Utica Saturday Globe [New York] February 15, 1913.

“Militant Maud Malone” The Yonkers Statesman February 3, 1913. “Miss Maud Malone, lone Empire State militant Suffragette, wants women to concentrate on the harrying of President-elect Wilson. This sort of thing is so foolish that it is a matter of National self-congratulations that the militant lady is a lone one. She will find few sympathizers in her wild plan of introducing foreign methods.”

The Troy Times July 7, 1913. “As an American militant suffragette Maud Malone occupies a position so isolated that the first letter of the surname looks as if it does not belong there – Louisville Courier-Journal."

“Clemency for Miss Malone” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle November 13, 1912. “It would be impertinent for The Eagle to offer advice to so self-confident a person as Miss Malone. But to any gentle maiden who may think of following her example we may say this, in all kindness: “It is never worth while to be made laughable in the eye of the community in which you expect to live, and in which you hope to be respected.”

[11] Shanley Catherine “The Library Employees Union of Greater New York, 1917-1929" Thesis (D.L.S. Columbia University, 1992) See footnote 61 on page 150.

[12] “Bull Moose Party Has Woman Leader…Maud Malone in Herd, Too” The New York Times August 11, 1912.

“IWW Here form League of Radicals” New York Tribune December 1, 1917.

[13]Shanley Catherine “The Library Employees Union of Greater New York, 1917-1929" Thesis (D.L.S. Columbia University, 1992) p. 154.

[14] Lola Paine “Maud Malone: She Pounded the Pavements for Suffrage” Daily Worker (New York Edition) August 26, 1945. “Even the Communist – and Maud is a Communist, The Daily Worker’s Librarian “who have put such a fight for minority groups have fallen down on the woman question” Maud Says. “And particularly the Communist women because they have a special role in this. Sometimes the women have to show the way, as we did way back, and then the men come along.” But the men had better get going, she says. Yes, Maud Malone is an old time fighter. But whether its 1905 or 1945, she’s ready to do her part to see that women once and for all, come into their own. It’s the order of the day, she says.”

[15] Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, “Salute to Maud Malone” Daily Worker New York February 14, 1951. “When we were very young, at the turn of the century, a young American woman appeared on the streets of New York, in a strange attire. There were ‘sanwich men,” poor old down-and-outers who trudged wearily, carrying signs advertising restaurants or clothing stores. But she was young, well dressed with quick brisk steps up and down Broadway, Fifth Ave. and other main thoroughfares. Her signs were startling and caused people to stop, read and discuss. They said, “Votes for Women.” She was Maud Malone, who died Wednesday at the age 78, the first militant suffragette in the United States. She antedated the Pankhursts of England by several years and was over a decade ahead of the militants of the Woman’s Party who went to jail in Washington shortly before the National Suffrage was won in 1920… Many who knew Maud Malone, this smiling willing librarian of the Daily Worker office who worked there nearly five years, did not know of her early tempestuous history and her extraordinary contributions to the women’s movement.”

Last updated: July 5, 2019