Proving Valor in War Seeking Equality Back Home

United States Army

At the heart of the modern Latino experience has been the quest for first-class citizenship. Within this broader framework, military service provides unassailable proof that Latinos are Americans who have been proud to serve, fight, and die for their country, the U.S. Thus, advocates of Latino equality often note that Latinos have fought in every U.S. conflict from the American Revolution to the current conflict in Afghanistan.

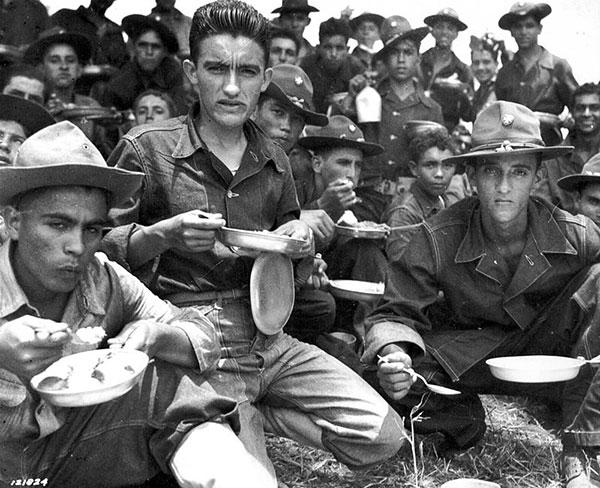

By 1940, people of Mexican descent in the U.S. were twice as likely to have been born and raised in the States than not. Often the children of immigrants who had entered in previous decades, they strongly identified with the country of their birth. The result was massive Mexican American participation in World War II, the most recent estimate being that some 500,000 Mexican Americans served in the conflict For many, a novel sensation of belonging accompanied the experience. Private Armando Flores of Corpus Christi, Texas, for example, fondly recalled being rebuked for putting his hands in his pockets on a cold day during basic training. "American soldiers stand at attention," a lieutenant told him, "They never keep their hands in their pockets." Years later, Flores still marveled at the significance of the occasion in his estimation: "Nobody had ever called me an American before!"

The massive mobilization effort that the war required, moreover, ensured widespread participation from non-combatants. Countless Latinas joined the Army's WACS, the Navy's WAVES, or similar all-female auxiliary units associated with the U.S. Air Force. Just 19, Maria Sally Salazar of Laredo, Texas, for example, was so eager to join the Army's Women Army Corps that she borrowed her sister's birth certificate so that she could pass for 21, the minimum age requirement for women. After basic training, she spent 18 months in the Philippine jungle working out of an administrative building but also tending the wounded when needed. In addition, thousands of Mexican American men and women found jobs in defense industries, an opportunity that was almost denied them because anti-Mexican prejudice remained so high. Although President Franklin Roosevelt had issued an executive order in 1941 banning discrimination in defense industry hiring, the war's seemingly ceaseless demand for labor soon proved more effective in trouncing employer reluctance to hire Latino workers. The upshot was that wartime sacrifice was often a family affair. The Sanchez family, transplanted from Bernalillo, New Mexico to Southern California before the war, is a case in point. Of ten grown siblings, three sisters each became a "Rosita the Riveter," while all five brothers served: two as army soldiers, one as an army medic, one as a Seabee, that is, a member of U.S. Navy Construction Battalion, and the eldest, who turned 50 during the war, as a civil defense air-raid warden. The family's participation was so extensive that members remember waiting to hear of one brother's fate during the Battle of the Bulge just after hearing another brother had died in combat in the Philippines.

With good reason, Mexican Americans took tremendous pride in their combat record during World War II. Thus, a tiny two-block lane in Silvis, Illinois, originally settled by Mexican immigrant railroad workers, earned the nickname "Hero Street" for sending an amazing 45 sons off to war. Sent to the Philippines because of their ability to use Spanish to communicate with their Filipino allies, many New Mexicans meanwhile experienced the horrors of the Bataan death march. Pinpointing ethnicity by looking at Spanish-surnames in addition to birthplace makes clear, moreover, that at least 11 Mexican Americans received the Medal of Honor during the conflict. Among them was Joseph P. Martínez, the child of immigrants and a Colorado beet harvester before the war. For leading a dangerous, but strategically critical, charge up a snow-covered mountain on the Aleutian Island of Attu, Martínez received that honor posthumously, the first draftee to do so. Many ethnic group members attributed their willingness to serve, and to serve so courageously to their unique cultural inheritance, one rooted in both Iberian and indigenous warrior societies. As Medal of Honor recipient Silvestre Herrera explained his decision to enter a minefield and single-handedly attack an enemy stronghold in France, a decision that cost him both feet in an explosion, "I am a Mexican-American and we have a tradition. We're supposed to be men, not sissies."

Not surprisingly, after the war, Mexican Americans found continued inequality deeply ironic and increasingly intolerable. In recognition of Herrera's heroism, for example, the governor of Arizona decided to name August 14, 1945 Silvestre Herrera Day. Unfortunately, in advance of that date the governor also had to order Phoenix businesses to take down signs that read, "No Mexican Trade Wanted." Similarly, at war's end, the owner of the Oasis Café in the town of Richmond, Texas, made clear that he only served an Anglo American clientele. When told to leave, however, Macario Garcia, another Medal of Honor recipient, refused to do so and instead got into a scuffle with the café owner. Although local city officials charged Garcia with aggravated assault, nationally he won in the court of public opinion, especially after the radio celebrity Walter Winchell decried the injustice of the incident on his program. Especially after fighting a fascist dictatorship that championed an ideology of racial supremacy, the idea that wartime sacrifice merited peacetime equality resonated with more Americans than ever.

By far the most famous instance of ill treatment directed at a Mexican American World War II veteran was the case of Private Felix Longoria of Three Rivers, Texas. It also contributed to the success of another civil rights organization dedicated to addressing Mexican American concerns. Four years after his combat death in the Philippines in 1945, Longoria's remains were shipped to the U.S. The local funeral home, however, refused a request by his widow, Beatrice, to use the funeral home's chapel for a wake in his honor. As the funeral home director explained then, "We just never made it a practice to let them [Mexican Americans use the chapel and we don't want to start now." He was correct. Across the Southwest, segregation against Mexican Americans endured less as a matter of law than as a matter of social custom. Yet what had been common practice before the war was no longer acceptable to Mexican Americans or to their Anglo American allies.

A Corpus Christi physician, Hector P. Garcia, led the charge to address the injustice. Garcia, who had served as a medic in Europe during the war, had upon his return to the States formed an organization called the American G.I. Forum to secure equal treatment for Mexican American veterans at Veteran Administration hospitals. Receiving a call from a Beatrice's sister to intervene in the dispute with the funeral home, Garcia called the funeral director himself to ask him to reconsider. He was quickly rebuffed. To Garcia, the irony of enforcing segregation even in the case of dead soldier amounted to a "direct contradiction of those principles for which this American soldier made the supreme sacrifice." Immediately, Garcia sent notes of protest to news media outlets, elected politicians, and high government officials. In response, Lyndon B. Johnson, then the junior senator from Texas, graciously arranged for Longoria to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. For Garcia, however, his work on the civil rights front had just begun. The Longoria incident propelled the American G.I. Forum to the front lines of the fight for Mexican American equality. Joining with LULAC, the Forum throughout the 1950s vigorously challenged segregation directed against Mexican Americans. So successful were the two organizations that the most overt manifestations of this practice as it was aimed at Mexican Americans substantially diminished by the end of the decade. Thus, a civil rights strategy born after World War I reached fruition after World War II.

Unfortunately, the experience of Puerto Ricans during World War II also echoed their experience during the previous global conflict. Once again, Puerto Ricans on the island eagerly registered for the draft or volunteered in the dual hope of contributing to the war effort and along the way helping their island through an infusion of defense dollars and technical training. Once again, military officials limited those hopes. Although the classic bolero La Despedida has its origins in the World War II era because so many soldiers left the island during those years, the military preferred to keep islanders in security and service roles. Charged mainly with hemispheric defense, members of the 65th Infantry Regiment (formerly the island's provisional regiment) were stationed as far away as the Galapagos Islands and again in the Panama Canal Zone, where some soldiers became subjects in army medical experiments about the effects of mustard gas. Army researchers concluded that Puerto Ricans burnt and blistered just like "whites." Finally, near the end of the war, a few island soldiers experienced combat directly. After being deployed to North Africa and Italy to guard supply lines, they came under assault from German forces in Europe. Meanwhile, about 200 Puerto Rican women contributed to the war effort by joining the WACS or WAVES. They received training in the States, and, unfortunately, in some cases experienced discrimination, before returning to Puerto Rico.

On the mainland, Puerto Ricans found ways to contribute, too. Puerto Ricans who served in the regular army units (versus service-oriented African American ones) likewise experienced combat. In addition, Puerto Ricans participated in D-Day and were at the Battle of the Bulge. In some cases, a single family sent sons to war from both the island and the continental U.S. Although many Americans families saw multiple sons go off to war, the stereotype of big, Catholic families certainly held true in the case of the "Fighting Medinas," who were seven brothers from a single Puerto Rican family divided between the island and Brooklyn, all of who served. Stateside, U.S. officials tapped Puerto Rican aviators for a special assignment: training African American pilots who became the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. Whether chosen to train black men or to be subjects of army medical tests, Puerto Ricans found that the military's continued preoccupation with racial difference framed their experiences during World War II.

Not until the Korean War did Puerto Ricans have the chance to prove themselves in battle in significant numbers. Following the surprise outbreak of war on the Korean peninsula in June 1950, the sudden and urgent need for manpower propelled the 65th Regiment to the front lines where they engaged in some of the most heated fighting of the entire war. Although the armed forces had been desegregated in 1948 by presidential order, the 65thRegiment, comprised entirely of islanders, remained an all-Puerto Rican unit. Proud of their service, they soon adopted the nickname the Boriqueneers, a name that was both a tribute to the island's original indigenous name, Boriquen, and possibly as well a nod to Puerto Rico's pirate past and the time of the buccaneers. Thrust in the thick of a war that featured a dramatically shifting front line across a rugged, mountainous terrain, these island soldiers also slogged through mud and snow as they faced both North Korean and Chinese enemy soldiers. By the end of 1951, the 65th Infantry Regiment had been in battle for 460 days, suffered 1,535 battle casualties and taken 2,133 enemy prisoners, meaning it had fought more days, lost fewer men, and taken more prisoners than comparable regiments on the front line. Little wonder that General Douglas MacArthur, who until April 1951 was in charge of military operations in Korea, said that the 65th "was showing magnificent ability and courage in field operations." A later study by the Office of the Governor of Puerto Rico also concluded that Puerto Ricans suffered disproportionate casualty rates as a result of the tremendous role played by the 65th.

For Puerto Rican politicians on the island, moreover, the Puerto Rican soldier exemplified the new working relationship they hoped to see between the island and the mainland. The 65th Regiment was both wholly Puerto Rican but also completely partnered to the U.S. Increasingly, Puerto Ricans had settled on a middle road between independence and statehood: they looked for maximum autonomy within the U.S. orbit. Thus, just as Mexican Americans used their military service to push for civil rights at home, Puerto Ricans used the demonstrated patriotism of the island's young men to ameliorate the colonial relationship between the island and the U.S. In the wake of World War II, islanders had received the right to elect their own governor. During the Korean conflict, U.S. officials decriminalized both the Puerto Rican flag and the Puerto Rican anthem for the first time since 1898. Shortly afterward, Puerto Rico officially became a Commonwealth of the U.S., a status between independence and statehood.

This is from an essay that focuses on Latinos in the United States military during the wars of the late 19th and entire 20th centuries as well as the peacetime roles of American Latino soldiers and veterans. The essay also discusses the economic and social significance of military service to American Latinos. It is from the National Park Service's Latino Heritage Initiatives Fighting on Two Fronts: Latinos in the Military by Lorena Oropeza

Tags

Last updated: September 11, 2023