Demanding Equal Political Voice...And Accepting Nothing Less

USDHEW

This American Latino Theme Study essay focuses on formal and informal efforts by various American Latino groups in the 19th and 20th centuries for full political and civic inclusion as citizens of the United States, including the development of Latino political activist groups, the struggle for civil rights, and the fight for full electoral rights for all citizens.

by Louis DeSipio

Over the past century and a half, diverse Latino communities have mobilized to demand civic and political inclusion, a process that has also facilitated the formation of a pan-ethnic political identity. Although there have been continuous gains, the quest for full and equal inclusion remains. The fact that the Latino population continues to grow in numbers and needs, and that this growth is often seen as a challenge to the majority population, ensures that Latinos will remain politically engaged in the pursuit of a full political voice in the upcoming decades.

Contemporary Latino politics is founded on generations of prior struggles for inclusion. These struggles have been organized around a consistent set of demands – ones that make the ongoing Latino struggle for civic and political inclusion a very American one – for equal protection of the law and the ability to participate equally in American society regardless of race or ethnicity. At the same time, like other racial/ethnic communities who are largely built on immigration, Latinos, particularly Latino immigrants, have sought to maintain transnational ties to their communities and countries of origin. This ongoing transnationalism among some immigrants has not diminished Latino efforts for inclusion in United States politics. Rather, transnational engagement often provides skills and networks that add to the resources for demanding inclusion in the U.S.

In the current essay, I will mostly focus on Mexican Americans and Mexican American organizations, particularly in the discussion of the historical roots of Latino struggles for inclusion. Mexican Americans were present in both larger numbers and higher concentrations than other Latino communities earlier in U.S. history. The pool of issues set by these early Mexican American organizations served, in part, as the foundation for pan-ethnic Latino organizing in the 1960s and beyond.

I will also focus primarily on collective efforts for inclusion; it is this collective demand and voice as Latinos that defines the Latino politics discussed in this essay. Prior to the contemporary era, collective efforts primarily took the form of community-based, civic, and trade union organizing. In the current era (the period after the civil rights revolution of the 1960s), electoral politics and voting added to the palette of collective political activities. This focus on collective activities is not to minimize the role of key individuals. Instead, it emerges from the recognition that the story of Latino political inclusion stems from diverse efforts across the country and across Latino national origin groups to build a collective and inclusive political voice that could be sustained (and expanded) over time.

Colonial and Immigrant Roots of Latino Demands for Political Inclusion

Latino collective organizing to achieve a civic and political voice is a largely 20th and 21st-century phenomenon. While the Latino presence in the U.S. pre-dates these 20th-century accomplishments, prior to the current era, Latino communities lacked the group resources, leadership, and organizations to demand equal rights in U.S. society. Consequently, demands were primarily individual rather than collective. Why was this the case? The story varies somewhat by region, but the primary answer is found in the form of colonial incorporation of early U.S. Latino populations.[1] In the Southwest, for instance, the former Mexican subjects who became U.S. citizens at the end of the U.S.-Mexican War had few resources that could be used for political organization.[2] Population concentration was low and most of the residents of the Southwest lived in a state of agricultural peonage. In the years just after the end of the U.S.-Mexican War, the former Mexican elite of landholders and civil servants could have served as an ethnic leadership. To some extent, this now Mexican American elite did share in the political leadership of the new states and territories of the U.S. Southwest, but their numbers were small. In addition, conflict quickly emerged throughout the Southwest between the former Mexican subjects and Anglo populations, many of whom were new migrants after the end of the war and who viewed the Mexican American population as racially subordinate.[3]

Consequently, in the years that followed the end of the U.S.-Mexican War, the economic and social status of much of these pre-conquest elite severely declined. Many lost their lands; others intermarried with Anglo migrants leading to the loss of ethnic identity within a generation or two. By 1900, there were few Mexican American leaders outside of the territory of New Mexico and the Mexican American community was almost entirely made up of agricultural workers and urban laborers. Neither had the resources to organize collectively nor to make more than sporadic political demands.[4]

New Mexico proves an exception to this pattern of declining political influence of pre-war elites and their children. European-descended whites did not migrate to the territory of New Mexico in the same numbers they did to other parts of the Southwest. As a result, the Hispano population of the territory continued to dominate state politics into the 20th century. The presence of the Hispano state leaders and their insistence on maintaining New Mexico's bilingualism, however, slowed the admission of New Mexico (and Arizona) as states.

The addition of Puerto Rico to the U.S. in 1898 did not lead to a beheading of the pre-existing elite comparable to the Mexican American experience in the Southwest.[5] Upon the U.S. invasion of the island, Puerto Ricans lobbied for a wide range of political demands, including U.S. citizenship, admission to the union, self-government, and to a lesser extent, independence. The Jones Act of 1917, which granted a limited form of U.S. citizenship to residents of Puerto Rico, and Public Law 600, which led to limited self-government in 1952, met some of these demands. These struggles, however, did not result in the full incorporation of Puerto Ricans into the U.S. They were largely fought from Puerto Rico during this period and involved few Latinos in the U.S.

Despite the fact that there was little collective action to demand civic inclusion in Mexican American and Puerto Rican communities in the late 19th century, there were efforts by individuals to highlight inequalities and obstacles. Mexican Americans in the Southwest, for instance, used the federal and state courts to assert their citizenship rights. Issues before the courts included the right of Mexican immigrants to naturalize (In re Ricardo Rodríguez [1897]), to hold public office (People v. de la Guerra [1870]), and to serve on juries or to be tried by juries that included Mexican Americans (George Carter v. Territory of New Mexico [1859]). The courts were also the locus of Mexican American demands for the enforcement of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo's protections of the property rights of Mexican Americans who had owned land in the Southwest before the U.S.-Mexican War.

During this period, local political machines also courted Latino voters. This form of organization existed in New Mexico and South Texas; the New York Democratic machine intermittently sought the votes of Puerto Ricans in some elections and excluded them in others as late as the 1950s. For the most part, however, these machines engaged Latino communities to serve the ends of the political parties and Latinos had little influence on the people their votes elected. In the early period of Mexican American presence in the Southwest, some unions organized Latino workers, particularly the mining unions and the anarchists. This union outreach was the exception rather than the rule, however, and did not add to the community's public leadership. Because of their concentration and the relatively lower share of whites, Mexican Americans in New Mexico (Hispanos) had more collective voice in this period than did Mexican Americans in other states. Several of the territorial governors were Hispano as were many members of New Mexico's 1910 Constitutional Convention (which preceded New Mexico's 1912 statehood).

Organized Latino Voices for Civic Inclusion in the Early 20th Century: Initial Steps

At the turn of the 20th century, Latinos started to organize more broadly to meet their collective needs, including the creation of insurance pools to meet end-of-life financial needs, but these efforts were largely apolitical. Early Latino civic organizing took on a more explicitly political dimension in the late 1920s and 1930s. This era saw the formation of the first regional Mexican American civic organizations as well as labor organizing that included the first "national" Latino political movement. It was these efforts that laid the foundation for post-World War II civic and political gains. The two organizations that formed in this era, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and El Congreso de Pueblos que Hablan Espãnol The Congress of Spanish-Speaking Peoples also refered to as El Congresso, represented different segments of the Latino community, but they shared a vision for a nation in which Latino voices were not muted by discrimination and exclusion.

LULAC was established in 1929.[6] Its founders included the small Mexican American middle class – largely small business owners – that had emerged over the previous 20 years in small towns in Texas. The goals of the organization were both revolutionary and assimilationist. Their leadership sought to challenge and reverse the discrimination that had characterized the treatment of Mexican Americans in the Southwest since 1848. They used the tools available to them as U.S. citizens, particularly the courts, to challenge the largely unquestioned position of whites and the long-dominant policy of anti-Mexican discrimination. Their core claim was equal protection as U.S. citizens under the law.

LULAC members did distinguish themselves, however, from recent immigrants of Mexican ancestry by limiting membership to U.S. citizens and conducting meetings in English. The organization offered assistance to Mexican immigrants seeking to naturalize, but did not believe there was a political or civic equality between non-naturalized immigrants and U.S. citizens. In the 1930s, LULAC conducted voter registration drives, encouraged members to support candidates who spoke to Mexican American concerns, organized to end the poll tax, and used the courts to challenge discrimination, particularly educational discrimination. Soon after its formation, LULAC sought to organize Mexican American women. In the early 1930s, several chapters formed Ladies' Auxiliaries. In 1938, the LULAC President established the position of National Organizer for Women, which was later changed to the National Vice President of the organization.

Despite their somewhat narrow focus and the middle-class status of the early members, LULAC chapters quickly emerged throughout the Southwest making it the first regional Latino organization. Moreover, LULAC's leaders developed a political alliance with Lyndon Johnson who was beginning his national rise in this period.[7] This alliance represented the first steps in building a Latino voice in national politics.

A decade after the formation of LULAC, Southern California union activists Luisa Moreno, Josefina Fierro de Bright, and Eduardo Quevedo established El Congreso.[8] It too represented a necessary step in the Latino demand for civic and political inclusion. Its membership was more urban, more working-class, and arguably more Latino in that it included more non-Mexicans than LULAC. It also offered a new model for Latinos of tactical alliances with other excluded groups in U.S. society. El Congreso also recognized women as organizers and leaders in a more central way than LULAC.[9] In addition, El Congreso was more short-lived. Yet, its membership and the issues that it articulated were closer to the majority of Latinos in the 1940s and beyond. Its rhetoric was more activist than that of LULAC, in large part based on its roots in the labor movement and labor's internationalism and ties to labor movements abroad in this era. The issues that it focused on – particularly the equal treatment of immigrants and citizens before the law – were ones that would have long-term resonance for Latino activism and that anticipated long-term changes in non-Latino attitudes in the post-war period.

At its core, however, El Congreso shared LULAC's demand for the end to anti-Latino discrimination and the elimination of barriers that denied Latinos an equal voice in U.S. society. El Congreso's vision extended to the elimination of barriers that limited civic, political, and economic opportunities for non-U.S. citizens. In addition, neither LULAC nor El Congreso was a mass organization. For most Latinos in the pre-civil rights era, the barriers that had long characterized the opportunities for Latino civic and political voice remained. Yet both organizations laid the foundation for the flowering of Latino demand making that would follow. They demonstrated that despite generations of discrimination, Latinos not only wanted a political voice, but also had the resources within the community to translate these demands into successful organization.

Latino Civic and Political Organizing in the Civil Rights Era

The 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s saw a rapid expansion in Latino demand making and the formation of diverse paths to political organizing. It also saw the foundation of Latino electoral influence. As was the case in the African American community and its civil rights movement in part of this period, leadership emerged from new segments of the population, including returning World War II and Korean War veterans and college educated young adults.[10] Contesting social inequality and continuing the fight against discrimination became central to the nascent Latino political identity of this era. Many of the organizations that formed in this period adopted a more confrontational rhetoric than had LULAC or El Congreso. These movements were not just united by their styles. Each was motivated by a rejection of unequal treatment based on race/ethnicity. In each case, anger over state-sanctioned discrimination and denial of rights was at the core of their mobilization efforts. As will be evident, these movements appeared in all parts of the country with concentrated Latino populations. Although they did not form a national Latino movement as we understand it today, their recognition of the shared experiences of Latinos nationwide laid the foundation for the pan-ethnic Latino politics that emerged in the post-civil rights era.

Early post-World War II activism transitioned Latino politics from civic organizing to electoral mobilization. Anger over the failure of Latino candidates to be elected to local offices in California and Texas led to the formation of community organizations focused on candidate recruitment, voter registration, and voter mo-bilization.[11] The result was a series of electoral "firsts" in which Latinos were elected to a specific office for the first time.

Latino youth, primarily U.S.-born young people, were among the most active. Their activism reflected Latino-specific concerns over discrimination and disparate outcomes, but also the anger of young adults in general in this era over the war in Vietnam.[12] Resentment over discriminatory public education spurred a series of walkouts (blowouts in the rhetoric of the era) in Los Angeles high schools. These spontaneous movements coalesced in organizing to reform the delivery of education and in anti-war mobilization under the auspices of the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO).[13] Similar efforts appeared in other areas of Latino concentration in the Southwest. The Crusade for Justice, formed in Denver, focused its energies on youth more broadly including young adults in schools and in (and out of) the workplace.[14] At its 1969 conference, the Plan Espiritual de Aztlán was presented publicly for the first time. The Plan is the founding document of the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicanos de Aztlán (MEChA) and called for Chicano self-determination and ethnic pride. MEChA is the only national Latino student organization on college and university campuses during this period still active today.

Young adults also led new movements to challenge white-dominated political institutions. They sought election to local offices in rural Texas, demonstrated that Mexican Americans could be mobilized, and use their numbers to challenge electoral discrimination.[15] These local efforts in the 1960s (and the national attention they drew) led to the formation of a regional Mexican American political party – La Raza Unida – that convened a national convention in 1972 and ran candidates for local and state offices throughout the Southwest.[16] Arguably, the presence of a Raza Unida candidate on the ballot reduced the Democratic vote sufficiently to elect the first Republican governor of Texas since the Civil War. Raza Unida candidates won local and a few state offices in this period.

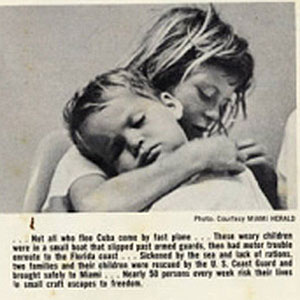

Young Latino adults also mobilized in Puerto Rican communities, which had grown dramatically after World War II.[17] Because of the Jones Act, which provided U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans, and the increased demand of cheap labor after the war, hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans made their way to New York, New Jersey, Philadelphia, and Chicago, and other cities. Puerto Rican migrants who seized this opportunity tended to be unskilled laborers and, later, rural migrants pushed off the land as Puerto Rican agriculture industrialized. Like the Mexican residents of the Southwest in the years after the U.S.-Mexican War, early 20th-century Puerto Rican migrants had few economic resources and were the targets of racial and ethnic discrimination.

Perhaps the most prominent of Puerto Rican youth groups of this era was the New York-based Young Lords, which had a different emphasis than the social movement organizations in the Southwest. Puerto Rico's colonial status ensured stronger ties to the homeland than existed among most Mexican Americans in this era. As a result, The Young Lords organized around a two-prong strategy. In New York and Chicago, they challenged discriminatory practices that denied Puerto Ricans the protections of their U.S. citizenship focusing on education, public health, public safety, and representation. They also sought, ultimately less successfully, to build a new independence movement on the island and build bridges between Puerto Ricans on the Island and the mainland.[18]

Civil rights era activism did not just appear among young adult Latinos. In New Mexico, the Alianza de Pueblos y Pobladores (The Alliance of Towns and Settlers) confronted federal and state authorities to enforce land claims by the descendants of Mexican residents of the state that had been largely neglected for the century since the ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.[19] Activists seized the ethos of the era to reinvigorate these claims using new and much more confrontational strategies, including the occupation of a federal courthouse. The United Farmworkers made the cause of California's primarily Latino agricultural labor force into a national issue and introduced non-Latinos in many parts of the country to the second-class status routinely experienced by many Latinos.[20] Combating high dropout rates in Puerto Rican communities was the focus of ASPIRA, formed by Antonia Pantoja and a group of Puerto Rican educators in 1961.[21] ASPIRA leaders recognized that the only way for Puerto Ricans (and, later, all Latinos) to achieve their leadership potential was to ensure educational opportunities.

The frequently confrontational style of these newly emerging organizations in this era – and their new generation of leaders – should not obscure the core of their demands. They sought full inclusion in U.S. society as guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution and saw, as the primary strategy to achieve that goal, the opportunity to elect the candidate of their choice to office. Although their rhetoric sometimes focused on the distinct experiences of Latinos and separateness, their demands and goals focused on the equal ability to compete in the civic and political world. In this, their pluralist demands were similar to those of other excluded groups in U.S. society seeking an equal voice.

The new opportunities for Latino civic organizing in the civil rights era were also not limited to challenging existing political structures from the outside. This era also saw the foundation of Latino voices within the major political parties and social institutions as well as the formation of Latino-led institutions to research, document, and articulate the Latino condition.

It was in this era that the "Latino vote" entered the rhetoric of the national parties and some elected leaders (it would be the 1980s before discussion of it became more common). John F. Kennedy relied on Mexican American votes in Texas to win the presidency in 1960; he earned these votes and probably increased the size of the Mexican American vote by running a well-financed campaign targeting Mexican Americans.[22] Richard Nixon made the first Republican claims on Latino votes nationally. He made some half-hearted efforts to reach out to Mexican Americans while his re-election campaign secretly funded La Raza Unida in an effort to reduce the Democratic vote. The Nixon campaign, and Republicans in general, were much more successful at winning support from Cuban Americans based in part on their strong opposition to Fidel Castro's regime in Cuba.[23] Each of the parties and many state parties established Latino outreach offices in this era.

Building on the organizational efforts of community-based voter mobilization efforts, Latinos began to elect co-ethnics to office, including national offices, in this period. Members of Congress elected in this era – Henry B. Gonzalez (TX), Edward Roybal (CA), Kika de la Garza (TX), Herman Badillo (NY), Manuel Lujan (NM), and Baltasar Corrada del Río (Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico) – ensured a Latino presence in Washington and in national policy making that didn't exist before. These Latino Representatives institutionalized their presence with the formation of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus in 1976.

Latinos also built their first national advocacy institutions in the civil rights era. Most prominent among these was the National Council of La Raza (NCLR) (formed as the Southwest Conference of La Raza). This alliance of Latino community-based organizations nationally had a twin mission. First, it provided capacity building to ensure that local Latino organizations could grow and expand service provision at the local level. Second, it sought to amalgamate the needs and issues identified by these member organizations into a regional and, ultimately, national Latino agenda that would serve as the foundation for Latino advocacy at the state and national levels. This organizational Latino voice provided an external resource for Latinos and non-Latino officeholders seeking to serve Latino needs. NCLR's advocacy targeted the legislatures and executive branch agencies.[24]

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) formed in this same period and with some of the same philanthropic supporters as NCLR targeted its energies on the courts. MALDEF and the Puerto Rican Legal Defense Fund (PRLDEF), founded four years later, ensured Latino communities would have the institutional talent to challenge discriminatory laws and practices. MALDEF's scope was broad, but it focused much of its energy on discrimination in schools, in public and private employment, in contracting, in the delivery of government services, in housing, and in employment as well as in voting rights and districting.[25] MALDEF's litigation on voting rights and districting ensured that Latinos could exercise their right to vote and that their votes would routinely have the opportunity to elect the candidate who received the most Latino votes. Over time, MALDEF has increasingly litigated on the rights of immigrants (a theme I return to later). ASPIRA also litigated a series of cases to ensure Puerto Rican and Latino educational access.

NCLR was by no means the only national Latino civil rights organization that formed in this era, although it probably had the broadest scope. The growing pool of Latino officeholders established the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials (NALEO). Activists in Texas who had become dissatisfied with some of the rhetoric of Raza Unida formed the Southwest Voter Registration and Education Project to challenge barriers to Latino registration and voting and to register Latinos to vote, initially with a focus on urban areas where the largest concentrations of Latinos resided.[26] Latino business owners created the National Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. Although it often took more conservative positions on economic issues than other Latino civil rights organizations, it too challenged discrimination and barriers to the equal participation of Latinos in U.S. society. MANA, a National Latina Organization to empower Latinas through leadership development and advocacy was formed in 1974.[27] LULAC and the G.I. Forum, which formed after World War II to fight discrimination experienced by returning Mexican American troops, continued to serve as voices for Latinos in this era and became more national in scope. They focused their resources on battling educational discrimination and litigated a number of important court cases.[28]

The national civil rights organizations that were founded in this period were not exclusively pan-Latino. Some organizations, formed initially to serve Mexican American communities such as NCLR or MALDEF, quickly expanded their focus to civil rights of all Latinos. Local organizations were more likely to focus primarily on the policy concerns of specific national origin groups. In the case of Puerto Rican and Cuban American communities, these community-level concerns included homeland issues as well, such as the status of Puerto Rico for Puerto Ricans or the vicissitudes of U.S.-Cuban relations for Cuban Americans.

The national Latino civil rights organizations that formed in this period reflected a new position of Latinos in U.S. society that would not have been possible had the more activist organizations not challenged local and state power structures that had denied Latinos equal protection of the laws. The national organizations were more explicitly pluralist in their rhetoric and operations, but they and the more activist organizations shared a vision of Latino empowerment by challenging barriers and expanding the Latino electoral and economic voice. Occasional activist rhetoric aside, the demands of the civil rights era focused on ensuring that the language of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution became the practice as well as the law of the land. The new national organizations ensured a new and permanent institutional resource to articulate the demand for Latino civic and political inclusion.

The Continuing Struggle for Latino Civic Inclusion in the Contemporary United States

Despite the breakthroughs of the civil rights period, struggles for Latino inclusion continued in the post-civil rights era. These contemporary efforts are, in some significant ways, different from those that preceded the 1960s. The major legislative legacies of the civil rights era were federal commitments to enforce the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing equal protection of the laws and equal access to the ballot box. Civil rights and voting rights legislation created a new playing field for Latino demands for civic inclusion; the advocacy organizations that were established in the civil rights era and the steadily growing number of Latino elected and appointed officeholders ensured that Latino voices would be heard on issues of importance to the community.

The demography of the community also changed. Changes to national immigration law as well as higher than average birth rates ensured that the Latino population grew more rapidly than other groups. By 2012, Latinos numbered more than 50 million and made up more than 16 percent of the national population (compared to approximately 6 million in 1960 who made up over just 3 percent of the U.S. population). The composition of the Latino community also diversified. Dominican populations migrated in large numbers to New York and the Northeast. Salvadoran and Guatemalan migrants moved in large numbers to Southern California and Texas. Florida saw large migrations from throughout the Americas; New York became home to many Columbian, Peruvian, and Mexican migrants as well as smaller populations of migrants from throughout the Americas. The geography of Latino migration also changed with large numbers of Latinos migrating to the South and rural parts of the Midwest where Latinos had not resided in large numbers. This changing Latino demography created the potential for greater divisions in the Latino political agenda. Potential cleavages include nativity and immigrant generation, national origin, region of residence, income, and education. It also put Latino communities into contact and potential conflict with non-Hispanic white populations who had not previously encountered many Latinos in their daily lives.

The Latino fight for civic inclusion thus continues. The contemporary barriers merge long-standing discriminations with newly emerging obstacles. Most important among these is the high share of non-U.S. citizens in the Latino population. Certainly, immigrants have always been more common in Latino than in white or black populations and non-naturalized immigrants have often faced exclusion from some forms of civic and political participation. What are new, however, are the high share of non-naturalized immigrants in the Latino (and Asian American) population and the growing share of immigrants made up of unauthorized immigrants who do not have a path to naturalization. It is, of course, difficult to present precise estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population. Yet, the best estimates suggest that of the approximately 11.5 million unauthorized immigrants resident in the U.S. in 2011, 8.9 million were Latino.[29] Whereas in the past, unauthorized migrants have been able to regularize their status over time, partisan polarization in Congress has prevented a compromise that would allow for a widespread legalization. This policy intransigence has spurred a new form of Latino civic activism among young adult undocumented migrants who migrated with their parents as young children. They have banded together as "Dreamers" tapping the nomenclature of the DREAM Act, which would offer a path to legal status to young adult unauthorized migrants who attended college or joined the U.S. military.

The future of Latino civic inclusion is not, however, just a story of ensuring that long-term unauthorized migrants are able to regularize their status (and eventually naturalize). Many long-term legal immigrants eligible for naturalization and interested in becoming U.S. citizens have not naturalized.[30] Again, there are no exact numbers, but the best estimates suggest that as many as five million Latino immigrants are eligible for naturalization, but have not naturalized. An additional 1.4 million will attain naturalization eligibility over the next five years (a population that will be continually replenished through new immigrants to permanent residence).[31]

The growth of both the legal permanent resident and unauthorized immigrant populations over the past 40 years has ensured that the share of the Latino population made up of non-naturalized immigrants grew as the number of immigrants increased in the 1970s and 1980s and will remain high for the foreseeable future. In 2008, for example, 37 percent of Latino adults were not U.S. citizens – and not eligible to vote – compared to 2 percent of non-Hispanic Whites and 6 percent of non-Hispanic blacks. In the era before high Latino migration, the immigration- and citizenship-related barriers to immigrant political voice were less absolute. Half the states allowed non-citizens to vote. The status of "unauthorized immigrant" didn't exist until the early 20th century, when Congress began to define categories of potential immigrants who were ineligible to enter the U.S.[32] Increasingly, the fight for Latino civic inclusion unites immigrant and U.S. citizen Latinos in a shared agenda that seeks to protect the rights and opportunities of immigrants, regardless of status, while providing encouragement for naturalization-eligible immigrants to naturalize and vote.[33]

The rapid growth in Latino migration in the contemporary era has created a new venue for political voice and activism. Immigrants have long sought the opportunity remain engaged in the civic life of their communities and countries of origin. Examples of these transnational connections can be found throughout the Latino experience in the U.S. (as well as those of other émigré populations). The long-standing immigrant desire to be involved in both the U.S. and the country of origin, however, is much easier to implement in the current era. Telecommunications and air travel are much cheaper than they have been in the past. The internet reduces communication costs further. Approximately 30 percent of Latino immigrants have engaged in the civic and political worlds of their communities and countries of origin, whether through membership in transnational organizations in the U.S. or through direct participation in the civic or political worlds of the country of origin. A higher share follow the politics of the country of origin.[34] These transnational connections diminish considerably in the second and later generations. Despite political transnationalism's roots in the long-standing immigrant desires to maintain a foot in the country of origin and the U.S., transnationalism as a mass phenomenon is relatively new. Countries of origin are seeking to promote long-term relationships with their émigrés.[35] To the extent that these efforts are successful, immigrant and perhaps second-generation transnational engagement will likely be a growing phenomenon in the future.

At the same time, the contemporary struggle for Latino civic and political inclusion is not simply a battle for immigrant rights.[36] U.S. citizen Latinos continue to face barriers to participation, some of which pre-date civil rights era reforms. Voter registration requirements, for example, were originally implemented to dampen the political power of turn-of-the-twentieth-century European immigrants.[37] They were effective then and continue to have a disproportionate and negative impact on young, poor, and less educated adults in U.S. society. Latinos are more likely to have high shares of the population in each of these categories. The colonial legacy of Puerto Rico denies the vote to the nearly four million residents of the Island. Constitutional design features also limit Latino influence. Both the U.S. Senate and the Electoral College weight the political influence of small states over large states; Latinos are more likely to live in the large states. The legacy of past discrimination remains in legislative district designs, at-large election systems, weekday elections, and in individual biases among non-Latino voters against Latino candidates. Few Latinos are elected from non-Latino majority or plurality districts while many Latino plurality/majority districts elect non-Latino candidates.

New and arguably more subtle forms of discrimination have emerged in the post-civil rights era. At present, the most insidious of these is voter identification requirements that many states are imposing. Latinos otherwise eligible to vote are less likely to have the required forms of identification and, consequently, will be less likely to vote. Requirements such as these that require implementation in multiple sites also raise the specter of unequal application of the law, which will further dampen Latino voting.

The organizational infrastructure that emerged in the post-civil rights era continues to advocate, litigate, and organize to address these issues and to expand the Latino political voice. Latino representation at all levels of elective office has increased steadily over the past 30 years. It has also become more diverse.[38] Latinas make up a higher share of Latino officeholders than do white women of white officeholders. Latino officeholders increasingly also include Latinos who trace their ancestry to the countries of Latin America that began to send large numbers of migrants to the U.S. after 1960. Two Latinos serve in the U.S. Senate and twenty-four serve as voting members in the U.S. House of Representatives. Of the House members, seven are Latinas, which represents a higher share of women than for Congress as a whole. The "Latino vote" is now routinely sought in national and many state-level races. A new generation of Latino campaign professionals has emerged to ensure that any candidate who wants to seek Latino votes can reach Latino voters. The national Latino organizations have banded together since 1988 under the rubric of the National Hispanic Leadership Agenda to articulate an agenda of the issues that unite Latino communities. Latino organizations also more continually offer support for Latinos seeking to naturalize. Voter registration efforts routinely expand prior to national elections. A particular target of these efforts is young adult Latinos. Voto Latino has been particularly effective at reaching young adults through popular culture. Latino community organizations and social service organizations have also expanded considerably in the post-civil rights era. Increasingly, Latino organizations and leaders are also able to use coalitional politics to achieve collective goals. These coalitions often include non-Latinos and non-Latino organizations around areas of common concern, such as immigrant rights with Asian American and Jewish organizations, civil rights and affirmative action with African American organizations, and pocketbook issues such as access to health care with unions and progressive Democrats. The size and growing political savvy of Latino communities ensures that these coalitions can be both effective at securing policy outcomes that benefit Latinos and providing the foundation for Latinos to develop leadership skills and seek elective office.

Conclusions

Despite changes in the structure of U.S. politics and the opportunities for Latino civic and political voice in the post-civil rights era, it is important to observe what has remained the same. The philosophy motivating mainstream Latino demands continues to be one of equal access to political rights and responsibilities. Latinos continue to need to challenge barriers to make their demands on political institutions. In 2006, in response to legislation passed in the U.S. House of Representatives making unauthorized immigrant status a crime, as many as five million people, most of whom were Latino, peacefully protested nationwide. The marchers included immigrant and native Latinos. The legacy of these marches included policy outcomes – criminalization was rejected by the Senate – and political gains. The rate of growth of the Latino electorate increased in 2008, at least in part in response to post-march drives to translate protest into votes. The Latino community was able to respond so quickly and, arguably, so effectively because institutions and organizations existed to channel anger and frustration into collective political voice. With growing numbers and increasingly sophisticated organization, Latinos continue to engage with old and new challenges, and in the process contribute to the renewing of democracy in the U.S.

Louis DeSipio, Ph.D., is a Professor of Political Science and Chicano/Latino Studies at the University of California, Irvine. His research interests include how democratic nations, particularly the United States, incorporate new members, especially because international migration has made most democracies home to large numbers of non-citizens just as those countries are seeking to incorporate ethnic and racial populations that were excluded or incompletely incorporated in the past. His major works include Making Americans, Remaking America: Immigration and Immigrant Policy; Counting on the Latino Vote: Latinos as a New Electorate; Beyond the Barrio: Latinos and the 2004 Elections; and Muted Voices: Latinos and the 2000 Elections. He received his Ph.D. degree in Government from the University of Texas at Austin.

Endnotes

[1] Juan González, Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America (New York: Viking, 2000).

[2] David G. Gutiérrez, Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995); and George J. Sánchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

[3] Arnoldo De León, They Called Them Greasers: Anglo Attitudes Toward Mexicans in Texas, 1821-1900 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983).

[4] Anselmo Arellano, "The People's Movement: Las Gorras Blancas," in The Contested Homeland: A Chicano History of New Mexico, eds. Erlinda Gonzales-Berry and David R. Maciel (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2000), 59-82.

[5] José Trías Monge, Puerto Rico: The Trials of the Oldest Colony in the World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997).

[6] Benjamin Márquez, LULAC: The Evolution of a Mexican American Political Organization (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993).

[7] Julie Leininger Pycior, LBJ and Mexican Americans: The Paradox of Power (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997).

[8] Sánchez; and Vicki Ruiz, Cannery Women, Cannery Lives: Mexican Women, Unionization, and the California Food Processing Industry, 1930-1950 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1987).

[9] Vicki L. Ruiz, "Luisa Moreno and Latina Labor Activism," in Latina Legacies: Identity, Biography, and Community, eds. Vicki L. Ruiz and Virginia Sánchez Korrol (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 175-192.

[10] Patrick J. Carroll, Felix Longoria's Wake: Bereavement, Racism, and the Rise of Mexican American Activism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003).

[11] Mario T. García, The Making of a Mexican American Mayor: Raymond Telles of El Paso (El Paso: Texas Western Press); and Kenneth Burt, The Search for a Civic Voice: California Latino Politics (Claremont, CA: Regina Books).

[12] Ignacio M. García, Chicanismo: The Forging of a Militant Ethos among Mexican Americans (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1997); and Ernesto Chávez, Mi Raza Primero: Nationalism, Identity, and Insurgency and the Chicano Movement in Los Angeles, 1966-1978 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

[13] Carlos Muñoz, Jr., Youth, Identity, and Power: The Chicano Movement (New York: Verso, 1989).

[14] Ernesto Vigil, The Crusade for Justice: Chicano Militancy and the Government's War on Dissent (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999).

[15] José Angel Gutiérrez, The Making of a Chicano Militant: Lessons from Cristal (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1998).

[16] Ignacio M. García, United We Win: The Rise and Fall of La Raza Unida Party (Tucson: The University of Arizona MASRC Press, 1969); and Armando Navarro, La Raza Unida Party: A Chicano Challenge to the U.S. Two-Party Dictatorship (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000).

[17] Miguel Melendez, We Took the Streets: Fighting for Latino Rights with the Young Lords (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2003).

[18] Young Lords Party, Michael Abramson and Iris Morales, Palante: Young Lords Party (New York: Haymarket Books, 2011).

[19] Reies López Tijerina, They Call Me "King Tiger:" My Struggle for the Land and Our Rights (Houston: Arte Público Press, 2000).

[20] Alicia Chávez, "Dolores Huerta and the United Farm Workers," in Latina Legacies: Identity, Biography, and Community, eds. Vicki L. Ruiz and Virginia Sánchez Korrol (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 240-254; and Miriam Pawel, The Union of Their Dreams: Power, Hope, and Struggle in Cesar Chavez's Farm Worker Movement (New York, Bloomsbury Press, 2010).

[21] Virginia Sánchez Korrol, "Antonia Pantoja and the Power of Community Action," in Latina Legacies: Identity, Biography, and Community, eds. Vicki L. Ruiz and Virginia Sánchez Korrol (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 209-224.

[22] Louis DeSipio, "The Pressures of Perpetual Promise: Latinos and Politics 1960-2003," in The Columbia History of Latinos in the United States Since 1960, ed. David G. Gutiérrez (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 391-420; and Ignacio García, Viva Kennedy: Mexican Americans in Search of Camelot (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2000).

[23] Susan Eva Eckstein, The Immigrant Divide: How Cuban Americans Changed the US and their Homeland (New York: Routledge, 2009).

[24] Deidre Martínez, Who Speaks for Hispanics? Hispanic Interest Groups in Washington (Albany: SUNY Press, 2009).

[25] Michael A. Olivas, No Undocumented Child Left Behind: Plyler v. Doe and the Education of Undocumented Schoolchildren (New York: New York University Press, 2012).

[26] Juan A. Sepúlveda, Jr., Su Voto es Su Voz: The Life and Times of Willie Velásquez (Houston: Arte Público Press, 2003).

[27] Benjamin Márquez, Constricting Identities in Mexican American Political Organizations: Choosing Identities, Taking Sides (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003).

[28] Henry A. J. Ramos, The American G.I. Forum: In Pursuit of the Dream, 1948-1983 (Houston: Arte Público Press, 1998).

[29] Michael Hoeffer, Nancy Rytina and Bryan Baker, Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States, January 2011 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2012); and Jeffrey S. Passel and D'Vera Cohn, Unauthorized Immigrant Population: National and State Trends, 2010 (Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center, 2011).

[30] Louis DeSipio, Counting on the Latino Vote: Latinos as a New Electorate (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996).

[31] Jeffrey S. Passel, Growing Share of Immigrants Choosing Naturalization (Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center, 2007).

[32] Mae N. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004).

[33] Kim Voss and Irene Bloemraad, eds., Rallying for Immigrant Rights: The Fight for Inclusion in 21st Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

[34] Louis DeSipio and Adrian D. Pantoja, "Puerto Rican Exceptionalism? A Comparative Analysis of Puerto Rican, Mexican, Salvadoran, and Dominican Transnational Civic and Political Ties," in Latino Politics: Identity, Mobilization, and Representation, eds. Rodolfo Espino, David L. Leal and Kenneth J. Meier (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007), 104-120.

[35] Rodolfo O. de la Garza and Harry P. Pachon, eds., Latinos and U.S. Foreign Policy: Representing the "Homeland?" (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2000).

[36] Rodolfo O. de la Garza and Louis DeSipio "Save the Baby, Change the Bathwater, and Scrub the Tub: Latino Electoral Participation After Seventeen Years of Voting Rights Act Coverage," Texas Law Review 71 (1993): 1479-1539.

[37] Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (New York, Basic Books, 2000).

[38] Sonia García, Valerie Martínez-Ebers, Irasema Coronado, Sharon Navarro, and Patricia Jaramillo, Políticas: Latina Public Officials in Texas (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008).

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Rio Arriba County Courthouse, Tierra Amarilla, NM Sign meant for migrant agricultural workers in Texas, 1949 Mural in Little Havana, Miami, FL LULAC Youth & Young Adults at the 2009 Washington Youth Leadership Seminar

Part of a series of articles titled American Latino/a Heritage Theme Study.

Last updated: July 10, 2020