Last updated: January 18, 2024

Article

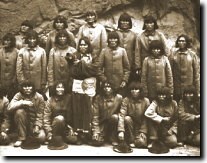

Hopi Prisoners on the Rock

Hopi History: The Story of the Alcatraz Prisoners

Wendy Holliday, Historian Hopi Cultural Preservation Office

One hundred years ago, in September 1895, 19 Hopi men from Orayvi (Oraibi) returned home after spending nearly a year imprisoned on Alcatraz Island. This article is the first step in an ongoing project to commemorate the 100th anniversary of their release and to document and record Hopi testimony about central events in Hopi history.

The story of the Alcatraz prisoners is one episode in an ongoing struggle between the Hopi people and the United States government. The late nineteenth century witnessed increased attacks on Hopi sovereignty and culture, as the United States government acted to "Americanize" the Hopi people. Imprisonment became the government's principal means of intimidation and punishment.

The U.S. government wanted to "Americanize" the Hopi by indoctrinating them with Anglo-American ideals and extinguishing Hopi culture. The education of children was the centerpiece of a U.S. government policy of Manifest Destiny, and it was fiercely resisted by Hopi people.

#57, Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas

All over the country, U.S. government agents coerced Indian children to go to non-Indian schools, most often off-reservation and miles away from home and family. At Hopi, pressure to send children to boarding schools began in earnest in 1887, when the first government school was established in Keams Canyon. Many Hopi parents refused to send their children to school so far away to learn the white man's ways.

In addition, the Keams Canyon School was in dismal condition. According the E.H. Plummer, the agent in Fort Defiance in 1893, the school was crowded and the buildings were inadequate. Disease was a problem in such a setting. Plummer wrote to the commissioner of Indian Affairs and explained his reluctance to force the school issue too strongly: "If deaths occur a strong prejudice will be aroused against the school, to say nothing of the policy of conducting a boarding school for any human pupils with such conditions of accommodations."

Despite these dangers, government agents tried to persuade parents to enroll their children in school voluntarily. Most resisted, and agents became increasingly frustrated with what they called "half-promises." Parents would tell the agents that they would send their children, but they never did, a strategy of passive resistance that worked for a short time.

The government also tried to bribe parents into sending their children to school. In January 1894, Plummer told the superintendent of the Keams Canyon School to stop issuing annuity goods and cease all work on houses and wells for the villages of Second Mesa. This was an especially calculating act, because Plummer noted that two feet of snow lay on the ground and the temperature was 17 degrees below zero.

The U.S. government most frequently resorted to force. In December 1890, for example, soldiers entered Orayvi and, through coercion and force, secured 104 children for the school in Keams Canyon. The same scene repeated itself in 1894 at Second Mesa. First, the government sent policemen to Second Mesa to round up children and bring them to the school in Keams. When this failed, School Superintendent Goodman requested soldiers to escalate the show of force in the villages.

Plummer suggested that having the troops take the children might not be wise. Instead, he suggested sending troops "to arrest and confine the headmen who are responsible for the children not being sent to school." Thus, the precedent for arresting village leaders who resisted the U.S. government was well established by 1894.

It was at about the same time that government officials began to report of two factions at Orayvi. Government agents called these two groups the Friendlies and the Hostiles. According to one of these agents, Constant Williams, "In the pueblo of Oraibi there are two factions, called by whites the 'Friendlies," and the 'Hostiles,' in about the proportion of one to two. The Friendlies sent their children to school and are willing to adopt civilized ways; the Hostiles, under the bad influence of Shamans, believe that the abandonment of old ways will be followed by drought and famine, to avert [this] they wish to drive the Friendlies out."

The government's division of Orayvi into Hostile and Friendly factions was inaccurate. Nearly all Hopis were, in fact, quite hostile to government efforts to wipe out all vestiges of Hopi culture. Friendlies, for example, resisted the government's land allotment program along with the Hostiles. Resistance or compliance with the government was not a clear cut issue. Many people complied with the government and sent their children to school out of sheer necessity to survive.

The government used overwhelming force against both factions and imprisoned people who resisted. Thus, the decision to send a child to school did not necessarily mean acceptance of the white man's ways.

In any case, tensions at Orayvi were mounting in the face of intensified pressure from the U.S. government to comply with its wishes. The government became increasingly frustrated with Hopi resistance to their efforts. To make matters worse, a land dispute between Navajos and Mormon settlers near Tuba City, Arizona was heating up.

Beginning in 1893, Agent Plummer reported to Washington that Navajos were trying to interfere with a dam built by Mormon settlers. By January 1894, tensions had increased to the point that Plummer feared bloodshed. In May, he wrote to the commissioner, "I fear very much that if attempt it made by the civil authorities to arrest the Indians by force that serious trouble will result."

#1, Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas

That trouble eventually spilled over into Hopi lands. Since the 1870s land around Munqapi and been farmed by Tuuvi, an emerging leader of Munqapi, and families from Orayvi who were sympathetic to those who became knows as Friendlies in the 1890s. As tensions were increasing in Orayvi over the education issue and divisions within the village, the hostility between whites and Navajos in Tuba City added fuel to the flames.

On October 10, 1894, Samuel Hertzog, the school superintendent, reported to Plummer that 30 hostiles had come to Munqapi, seized the fields, and planted them in wheat. According to Hertzog, "This is the first act of hostilities." Hertzog also suggested that these hostilities might have had more to do with the local tensions around Tuba City: "May be because a Mormon and a Navajo stole one man's corn and afterward came and cut the fodder and told Ololomai (Loololma, Kikmongwi [leader/chief] of Orayvi) to get out."

For a variety of reasons, in October 1894, 50 Hostiles did go to Munqapi and plant the lands that had traditionally belonged to their clans. The government, in their strategy of divide and conquer, predictably took the side of the Friendlies. Agent Plummer asked Washington to send two troops of cavalry to adjust the difficulties and, he wrote, "if necessary arresting such of the Hostile element as have appropriated lands belonging to the friendly element." He continued, "The rights of property and of person of well behaved, industrious Oraibas and Navajos are being trampled upon and abused and unless prompt measures are taken by the Department murder and bloodshed will follow."

Nothing was done, however, until November, when the new Navajo/Hopi Agent, Constant Williams, reported for duty in Fort Defiance. His first action as agent was to go to Orayvi to hear the reports of differences.

On November 6, in the presence of the entire village, Loololma made the following statement to Williams: "He and his people perceiving the advantages to be derived from education and the adoption of Washington ways (i.e. civilized habits) had sent their children to school; that the Hostiles, finding persuasion useless to make them give up this course, had first threatened them with deprivation of their fields and expulsion from their country into Mexico, and, finally, that the Hostiles had now sent a part of fifty men over to Moencopi, had seized the fields of the Friendlies there and had planted them with wheat; that the Friendlies, being outnumbered could no more than protest and report to the agent: that they were sincerely desirous of walking in the Washington way: and that they wished for soldiers to settle the difficulty."

Lomahongewma, Spider Clan, and Heevi'ima, Fire Clan, both rivals to Loololma, replied that Loololma's facts were true. According to Williams, "They said for themselves that they do not want to follow the Washington path; that they do not want their children to go to school; that they do not want to wear the white man's clothes; that they do not want to eat the white man's food; that they do want the white man to let them alone and to allow them to follow the Oraibi path; and they bitterly denounced the Friendlies for departing from the Oraibi path. They said that they had taken the Moencopi fields because they had anciently belonged to them, although they admitted that the Friendlies had had peaceful possession of them for many years; they added that in the spring they intended to take away the fields not cultivated by the Friendlies around the mesa of Oraibi. And they concluded by saying that they also wished to have troops come. I asked them if they could not adjust their differences in a peaceable talk and they replied 'no, that this trouble can never be settled until the soldiers come.'"

Williams responded by saying that the Hostiles had been forbidden by Agent Plummer to disturb the Friendlies and their fields. Thus, they should not expect to harvest the crop or take away the Friendlies' fields around Orayvi. In addition, "Their desire for the presence of troops would be gratified." At this point, the meeting ended. Williams returned to Fort Defiance where he wrote this report.

#60, Mennonite Library and Archives,

Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas

On that same day, November 15, 1894, he requested two cavalry companies with Hotchkiss guns to be sent from Colorado. He wrote, "The Friendlies must be protected in their rights and encouraged to continue in the Washington way, and being convinced that this can only be done by a display of force and the arrest of the principal men engaged in the disorders."

And so, on November 25, troops came to Orayvi and arrested 19 Hostiles: Heevi'ima, Polingyawma, Masatiwa, Qotsventiwa, Piphongva, Lomahongewma, Lomayestiwa, Yukiwma, Tuvehoyiwma, Patupha, Qotsyawma, Sikyakeptiwa, Talagayniwa, Talasyawma, Nasingayniwa, Lomayawma, Tawalestiwa, Aqawsi, and Qoiwiso.

Because they were arrested by government troops, these men were taken first to Fort Defiance, and then to Alcatraz, a military installation on a harsh island of rock in San Francisco Harbor. These men spent nearly a year at Alcatraz because the government had once again resorted to its ultimate form of coercion at Hopi: military force.

On January 4, 1895, the San Francisco Call published a story under the headline "A Batch of Apaches." The article stated, "Nineteen murderous-looking Apache Indians were landed at Alcatraz island yesterday morning." The article misidentified the 19 Hopi men who had been arrested at Orayvi the previous November. The article is filled with racial stereotypes of murderous and "crafty redskins" who refused to live according to the "civilized ways of the white men." In February, the same newspaper published another story about the "Moquis on Alcatraz."

The article claimed:

"Uncle Sam has summarily arrested nineteen Moqui Indians...and taken them to Alcatraz island, all because they would not let their children go to school. But he has not done it unkindly and the life of the burnt-umber natives is one of ease, comparatively speaking. They have not hardship aside from the fact that they have been rudely snatched from the bosom of their families and are prisoners and prisoners they shall stay until they have learned to appreciate the advantage of education."

In 1995, the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office began a project to record the history of the Alcatraz prisoners. It began with an article in the Tutuveni about the events leading to the arrest of the prisoners. As the San Francisco newspaper suggested, the men were imprisoned because they opposed the government's program of forced education and assimilation. The Tutuveni article was based upon government records. Subsequent research uncovered these San Francisco newspaper articles. While they shed light onto the story of the Alcatraz prisoners, they are all told from the point of view of the white government and Anglos who supported the forced education program.

These viewpoints often reflected callous disregard for the human suffering of the Hopi prisoners. The San Francisco newspaper article wrote that the prisoners' days were generally spent sawing large logs into shorter lengths. Occasionally, their work was interrupted by trips into San Francisco to visit the public schools, "so that they can see the harmlessness of the multiplication table in its daily application." Their accommodations were the same as that of the white military prisoners, and their food was "like that of any ordinary second-class hotel."

According to the Call, "It is even difficult to find work for them at times. They rise early, breakfast, go to work, if the weather is fine, eat their dinner at noon and then work all afternoon. This is followed by tea or a wholesome equivalent for it and then bed. Their taskmaster is a good-natured, well educated young man with a sympathetic understanding of their condition that makes it easy for him to deal with them and keeps them in even humor."

#50, Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas

According to the newspaper, the Hopi prisoners were treated rather well. The article claimed that the prisoners' only grievance was being taken from their homes and families. In fact, other sources provide glimpses into very real hardships faced by both the prisoners and their families back at Hopi. John Martini described the prisoner's cells at Alcatraz as "tiny wooden cells...worlds removed from the western desert and plains." Indeed, a description of Alcatraz in 1902, just seven years after the Hopi prisoners were jailed there, suggests that the cells were in poor condition: "The old cell blocks were `rotten and unsafe; the sanitary condition very dangerous to health. They are dark and damp, and are fire traps of the most approved (sic) kind.

Furthermore, taking the prisoners from their homes and families was more than "rude." In a series of letters between H.R. Voth, a Mennonite missionary at Orayvi, and Guruther, the Commanding Officer at Alcatraz, family members at Hopi were extremely worried about the prisoners. There were rumors that some of them had died.

In August, Voth wrote to the Guruther that the pictures of the prisoners were "very much appreciated by relatives and friends" because rumors had circulated that they were "poorly fed, clothed, worked hard, some had died, etc. were perhaps killed."

In September, Voth wrote to Lomahongiwma to report on the prisoners' families and the crops. These reports must have caused considerable anguish among the prisoners, especially those who were separated from their families during important ceremonies and planting and harvesting. In addition, two of the prisoners' wives gave birth to children who died while the men were at Alcatraz. Being torn from their villages and families was certainly more than a rude inconvenience.

The story of the Alcatraz prisoners, in the written historical records, is incomplete. It is based solely on written records and is missing Hopi perspectives. The Cultural Preservation Office would like to complete a written account of the Alcatraz prisoners by using Hopi remembrances and stories. We would like to gather stories of the actual hardships endured by the prisoners at Alcatraz, as well as the friends and families left behind to raise families, plant and tend to the crops, and worry about their loved ones imprisoned in a distant place. The Cultural Preservation Office has been able to trace some of the descendants of the prisoners. We have a current list of these descendants on file. If you would like to share any stories about the prisoners' experiences at Alcatraz or the lives of their families while they were imprisoned, please contact Leigh J. Kuwanwisiwma, at the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office at 928-734-3611.

Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas

The following is a list of the Alcatraz prisoners and their clans.

Aqawsi (Kwaa/Eagle)

Heevi'yma (Kookop/Fire)

Kuywisa (Kookop/Fire)

Lomahongiwma (Kookyangw/Spider)

Lomayawma (Is/Coyote)

Lomayestiwa (Kookyangw/Spider)

Masaatiwa (Kuukuts or Tep/Lizard or Greasewood)

Nasingayniwa (Kwaa/Eagle) Patupha(Kookop/Fire)

Piphongva (Masihonan/Grey Badger)

Polingyawma (Kyar/Parrot)

Qotsventiwa (Aawat/Bow)

Qotsyawma (Paa'is/Water Coyote)

Sikyaheptiwa (Piikyas or Patki/Young Corn or Water)

Talangayniwa (Kookop/Fire)

Talasyawma (Masihonan/Grey Badger)

Tawaletstiwa (Tasaphonan/Navajo Badger)

Tuvehoyiwma (Hon/Bear)

Yukiwma (Kookop/Fire)

You can learn more about American Indian prisoners held on the Rock by the U.S. Army here.

Tags

- alcatraz island

- site of conscience

- alcatraz

- prisoners

- hopi

- sovereignty

- manifest destiny

- boarding schools

- keams canyon school

- orayvi

- navajos

- agent plummer

- resistance

- munqapi

- tuuvi

- tuba city

- samuel hertzog

- mormon

- constant williams

- loololma

- moencopi

- spider clan

- heevi'ima

- fire clan

- fort defiance

- indigenous heritage

- native american

- native american history

- alcatraz- military period

- island