Last updated: October 27, 2021

Article

Helen Lee Franklin

Boston served as one of the many destinations for African American southern migrants searching for new economic opportunities and fleeing discrimination during the Great Migration. This article highlights the journey of one of these southern migrants who settled in Boston, as shared on Boston National Historical Park’s Stories of the Great Migration page.

A native South Carolinian, Helen Lee Franklin moved to Massachusetts with her family as a young girl. When a young adult, she returned to the South to teach. Possibly due to her experiences in the South, Franklin became a community organizer and activist in Cambridge and Boston. Her Great Migration story demonstrates how she spoke up against injustice and fought for equality throughout her life.

Explore the story-map below to learn about Helen Lee Franklin’s Great Migration journey. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll down to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes

[1] According to Ambassador Harriet Lee Elam-Thomas, Helen Lee and her family’s relative was Samuel J. Lee, one of the three founders of Aiken County. (Elam-Thomas, Diversifying Diplomacy, 19).

Harriet Lee Elam-Thomas with Jim Robison, Diversifying Diplomacy: My Journey From Roxbury to Dakar (Nebraska: Potomac Books, 2017), 19.; Walter Edgar, ed., The South Carolina Encyclopedia Guide to the Counties of South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2012), ProQuest Ebook Central, 8-9.; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1900, Aiken, Aiken, South Carolina, Enumeration District 0022, page 10.

Image: Palmer, James A. "No. 64, Richland Avenue, recto." Stereograph. Chibbaro Stereograph Collection: 186u-1997. South Caroliniana Library. University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C.

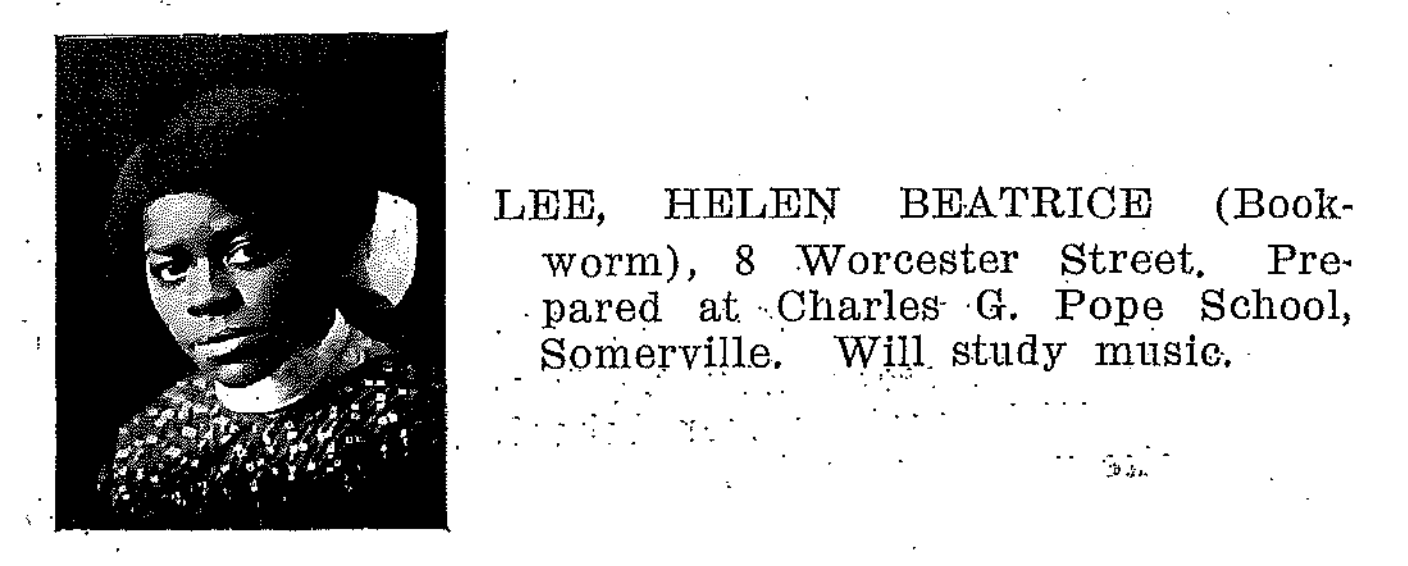

[2] United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1910, Somerville Ward 2, Middlesex, Massachusetts, Enumeration District 0992, Roll T624_604, page 12B.; Cambridge High and Latin School, Cambridge High and Latin School Yearbook, Cambridge, 1914.

Image: Cambridge High and Latin School. Cambridge High and Latin School Yearbook. Cambridge, 1914.

[3] “Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown,” North Carolina Historic Sites, February 2020, https://historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/charlotte-hawkins-brown-museum/history/dr-charlotte-hawkins-brown.; Ambassador Harriet L. Elam-Thomas, interviewed by James T. L. Dandridge, II, June 2, 2006, oral history, The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project. https://adst.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Elam-Thomas-Harriet-L.pdf.; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1920, Cambridge Ward 4, Middlesex, Massachusetts, Enumeration District 47, Roll T625_708, page 6B.

Image: Commencement activity outside of Stone Hall, Palmer Memorial Institute. Charlotte Hawkins Brown Papers. Folder: Photographs: Students, events, buildings, n.d. Sedalia Public School, 1938-39, n.d. HOLLIS collection level record 000605309 . RLG collection level record MHVW85-A64. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. https://images.hollis.harvard.edu/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=HVD_VIAolvwork20013559&context=L&vid=HVD_IMAGES&search_scope=default_scope&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US

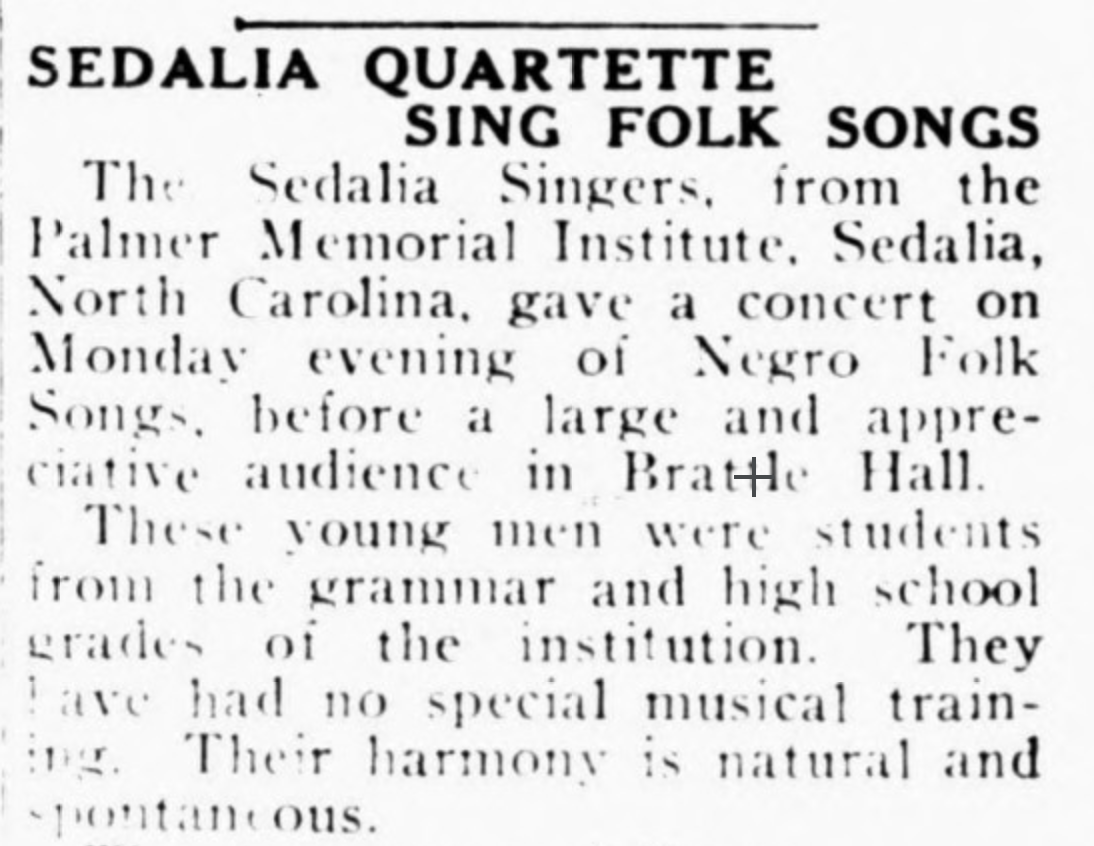

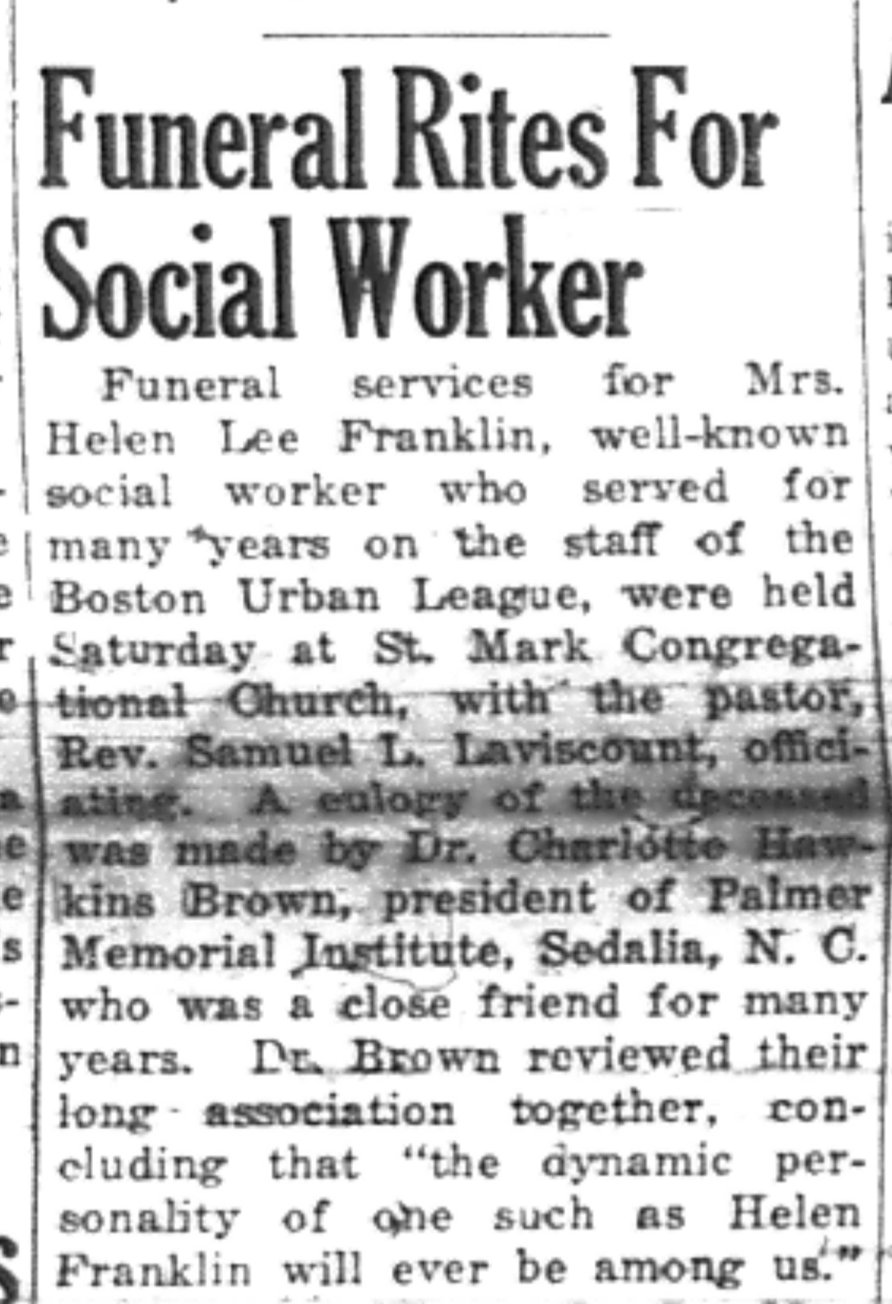

[4] "Sedalia Quartette Sing Folk Songs," Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Mar. 15, 1924, 7, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19240315-01.2.64&srpos=2&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-sedalia+quartette------. “Funeral Rites for Social Worker,” Boston Chronoicle (Boston, MA), Jan. 29, 1949, 1.

Image: "Sedalia Quartette Sing Folk Songs," Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Mar. 15, 1924, 7, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19240315-01.2.64&srpos=2&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-sedalia+quartette------.

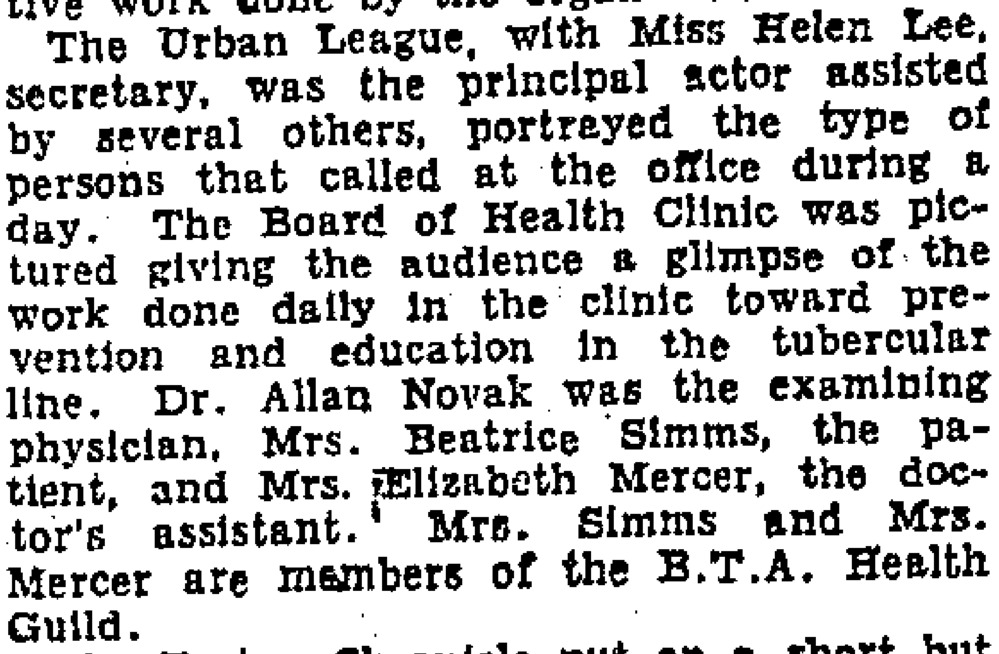

[5] Odile Sweeney, “Community Center Plans New Building in 1947,” Cambridge Chronicle (Cambridge, MA), 1946, 39.; “Benefits Cambridge Community Centre,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), May 18, 1929, 1, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19290518-01.2.5&srpos=11&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-%22helen+lee%22----- ; “New Community Centre Opened Tuesday Night,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Aug. 10, 1929, 2, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19290810-01.2.14&srpos=12&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-%22helen+lee%22------ ; “Staff Meeting At Community Center” Cambridge Chronicle and Cambridge Sun (Cambridge, MA), Apr. 2, 1936, 9. ; “Community Center has its first Demonstration,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Oct. 24, 1931, 1, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19311024-01.2.7&srpos=4&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-%22helen+b.+lee%22------ ; C. Elliot Freeman Jr., "Boston News," The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967) (Chicago, IL), May 6, 1933, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender, 20.

Image: Cambridge Community Center, http://www.cambridgecc.org/photo-archive.html.

[6] "Boston," Afro-American (1893-1988) (Baltimore, MD), Apr. 25, 1931, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, pg. 18. “Our Milestone,” Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts, accessed January, 2020, https://www.ulem.org/centennial; Robert C. Hayden, “A Historical Overview of Poverty among Blacks in Boston, 1850-1990.” Trotter Review 17, no. 1 (September 2007), 137, https://archive.org/details/trotterreview171willi/page/136/mode/2up.

Image: "Boston," Afro-American (1893-1988) (Baltimore, MD), Apr. 25, 1931, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 18.

[7] “Commonwealth of Massachusetts Probate Court,” Cambridge Sentinel (Cambridge, MA), Sept. 26, 1931, 5, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Sentinel19310926-01.2.40.4&srpos=8&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-%22helen+b.+lee%22------ ; “Delinquent Tax Sales Collector’s Notice,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Dec. 8, 1933, 8, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19331208-01.2.91&srpos=13&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-%22helen+b.+lee%22------; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1940, Boston, Suolk, Massachusetts; Enumeration District: 15-399, Roll: m-t0627-01669, page 12A; Department of Public Health, Registry of Vital Records and Statistics. Massachusetts Vital Records Index to Deaths [1916–1970]. Volumes 66–145. Facsimile edition. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

Image: G.W. Bromley & Co.. "Atlas of the city of Boston, Roxbury." Map. 1931. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:1257c411w

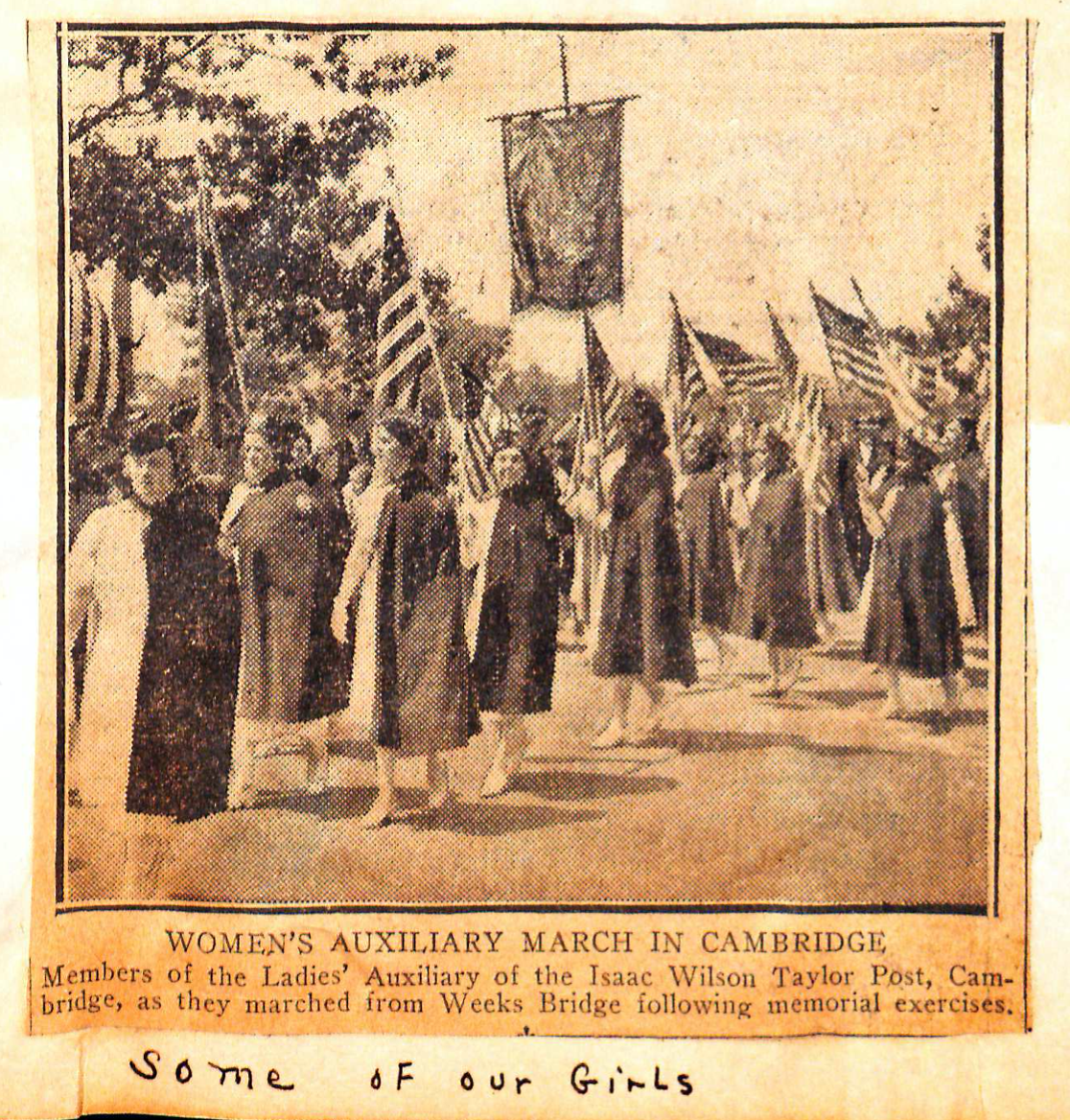

[8] Musical and Tea, section of yearly history, 1939, "Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1939-1940" (Folder 8), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300

Image: "Women’s Auxiliary March in Cambridge," newspaper clipping, "Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1940-1941" (Folder 9), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300

[9] List of Officers, 1934, 1935, 1936 "Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1934-1938" (Folder 7), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300

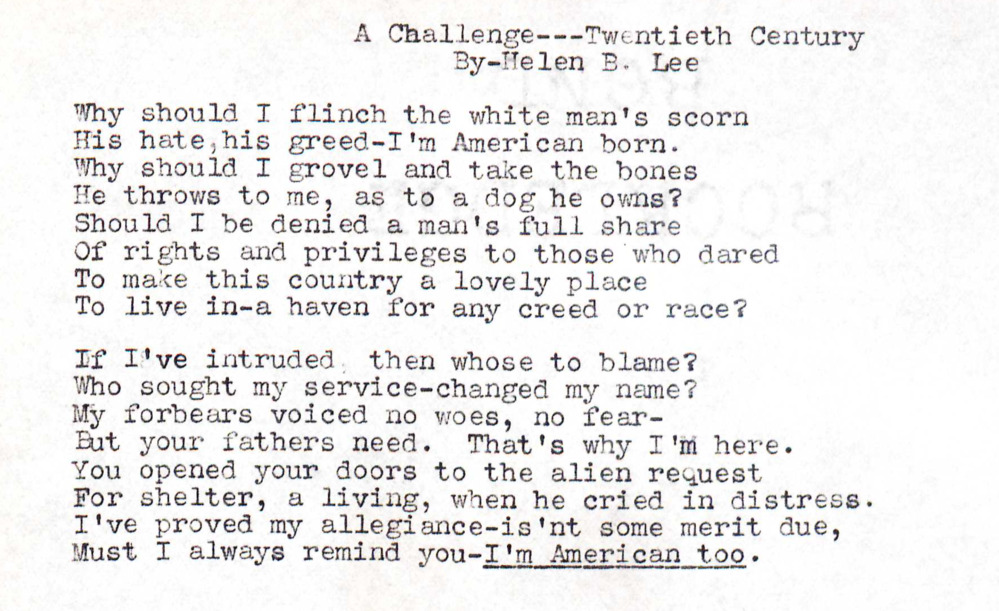

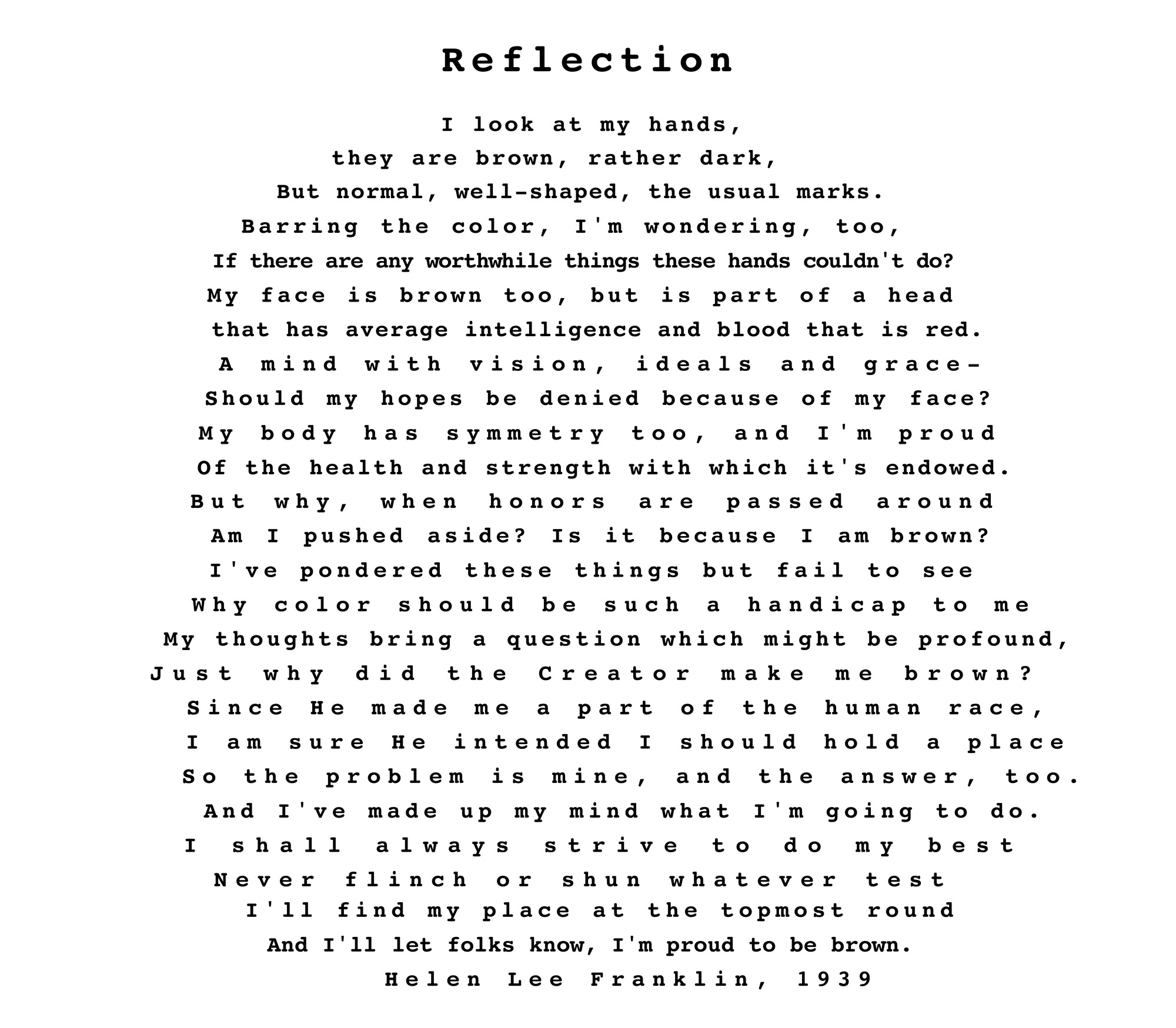

Image: "A Challenge, 1939," Poem from scrapbook, page with two poems by Helen B. Lee, 1939, "Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1939-1940" (Folder 8), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300

[10] Joseph A. Smith, Regional Director, War Manpower Commission, to Lieutenant Commander Paul S. Strecker, Personnel Division, Boston Navy Yard; Fair Employment Practice Committee, December 17, 1943; Boston Navy Yard, 1-GR-55, 1943-1944; Closed Regional Case Records, 1943-1946, Box 1; Records of the Committee on Fair Employment Practice 1940-1946, Record Group 228; National Archives at Boston.; Helen Lee to Julian D. Steele, August 9, 1943, Julian D. Steele Collection, NAACP Correspondence 1929-1947, Box 20, Folder 5, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts.; Elam-Thomas, Diversifying Diplomacy, 20-21.

Image: Boston National Historical Park: Image ID = 9369-2.

[11] To learn more about this case, read this article Discrimination and African American Women at the Charlestown Navy Yard.

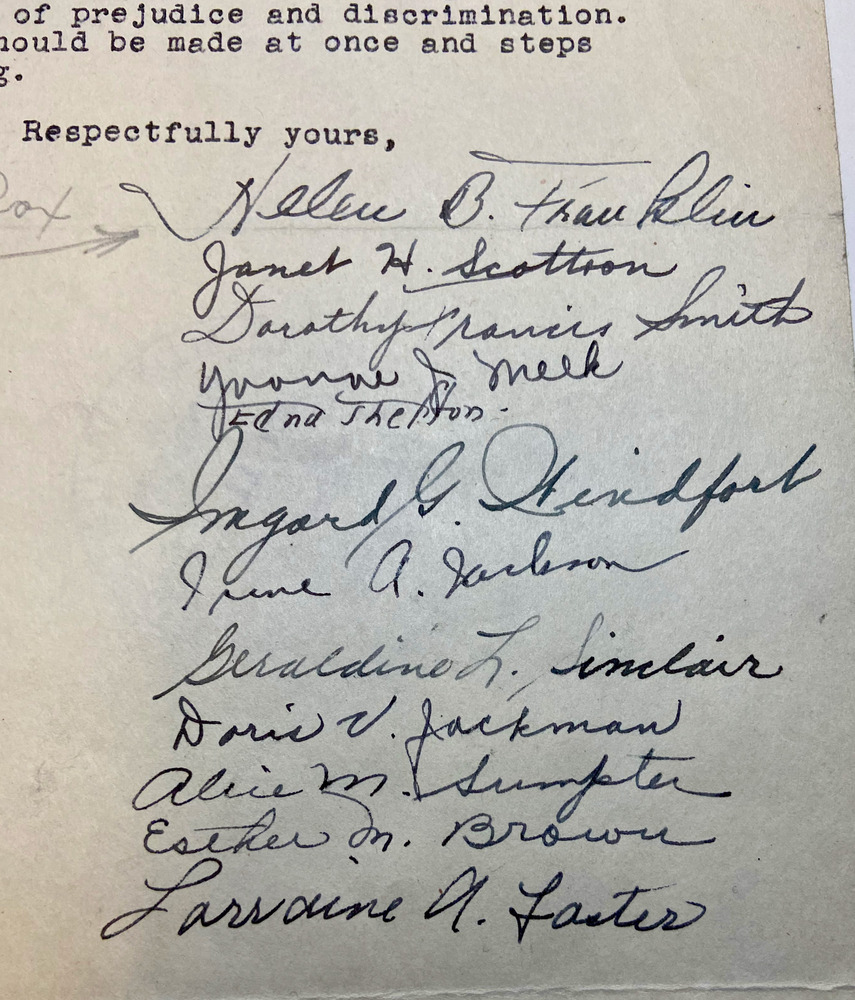

11 other women: Janet H. Scottron, Dorothy Francis Smith, Yvonne J. Meek, Edna Thefton, Imgard G. Windfort, Irena A. Jackson, Geraldine L. Sinclair, Doris V. Jackman, Alice M. Sumpter, Esther M. Brown, Larraine A. Foster.

Helen Franklin et al. to Richard Walker, Fair Employment Practice Committee, November 6, 1943; Boston Navy Yard, 1-GR-55, 1943-44; Closed Regional Case Records, 1943-46, Box 1; Records of the Committee on FEP 1940-46, Record Group 228, National Archives.; “Miss Helen Lee, C. Franklin Wed,” Afro-American (1893-1988) (Baltimore, MD), Oct 16, 1943, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, pg. 12.

Image: Helen Franklin et al. to Richard Walker, Fair Employment Practice Committee, November 6, 1943; Boston Navy Yard, 1-GR-55, 1943-44; Closed Regional Case Records, 1943-46, Box 1; Records of the Committee on FEP 1940-46, Record Group 228, National Archives.

[12] Julian D. Steele to Helen Franklin, November 19, 1943, Julian D. Steele Collection, NAACP Correspondence 1936-1944, Box 20, Folder 6, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts.

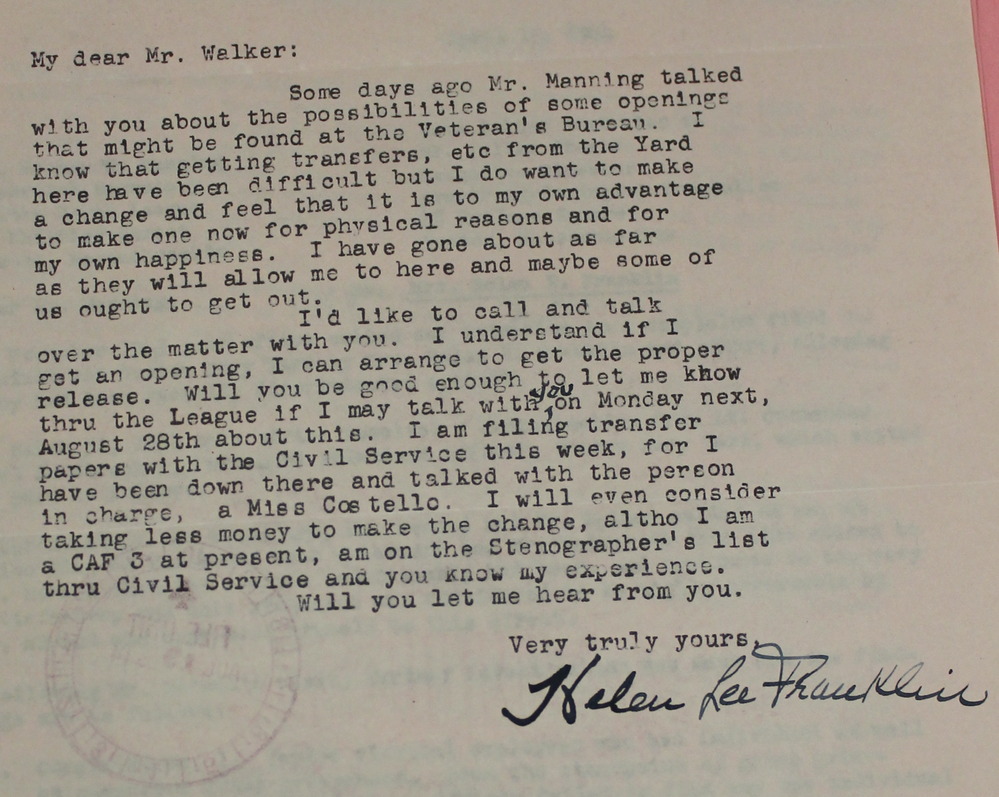

Image: Department of Defense. Department of the Navy. Naval Photographic Center. (12/1/1959 - ca. 1998). Record Group 80: General Records of the Department of the Navy, 1804 - 1983. National Archives. Local Identifier: 80-G-218855, https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2017/08/10/researching-wwii-navy-ships/

[13] Final Disposition Report, April 12, 1944; Boston Navy Yard, 1-GR-55, 1943-1944; Closed Regional Case Records, 1943-1946, Box 1; Records of the Committee on Fair Employment Practice 1940-1946, Record Group 228; National Archives at Boston.; Helen Franklin to Richard Walker, War Manpower Commission, August 15, 1944; War Manpower Commission. Regional Correspondence Files, Region I, Mass. 1943. Box 17:5; War Manpower Commission Central Files 1942-1945, Record Group 211, Series 269, NAID 6278149. National Archives.

Image: Helen Franklin to Richard Walker, War Manpower Commission, August 15, 1944; War Manpower Commission. Regional Correspondence Files, Region I, Mass. 1943. Box 17:5; War Manpower Commission Central Files 1942-1945, Record Group 211, Series 269, NAID 6278149. National Archives.

[14] “Funeral Rites for Social Worker,” Boston Chronicle (Boston, MA), Jan. 29, 1949, 1, 8.

Image: “Funeral Rites for Social Worker,” cropped image, Boston Chronicle (Boston, MA), Jan. 29, 1949, 1.

[15] Elam-Thomas, Diversifying Diplomacy, 20-21.

Image: NPS/Woods, Based on poem: "Reflection," Poem from scrapbook, page with two poems by Helen B. Lee, 1939, "Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1939-1940" (Folder 8), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300.