NPS Photo

This article has been adapted from An Ethnohistorical Overview of Groups with Ties to Fort Vancouver, by Douglas Deur, Ph.D. The entire report can be read online here.

When considering the tribal associations with Fort Vancouver during the period of Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) occupation (1824-1860), one of the most important but overlooked dimensions of this issue is the role of Native women at the fort. Records and journal accounts suggest that nearly all of the men working as officers and employees at the fort had families, and almost all of these families were of mixed ethnicity, with American Indian or Métis wives. Indeed, women made up almost half of the total population of the Fort at the apex of its operations and, if enumerated together with their children, this segment of the fort community appears to have comprised more than two-thirds of its population. Yet, despite their clear importance, the largely Native female population of the fort community was almost invisible in the official records of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Written information regarding this population is elusive, appearing only in reminiscences and diaries, certain church records, and a smattering of other documents. What follows is a summary of the role of interethnic marriages at Fort Vancouver as suggested by these sources.

Interethnic Marriages in the 19th Century Fur Trade

Interethnic marriages were part of the fur trading experience from long before the arrival of Europeans on the lower Columbia River. The success of fur trading operations was often contingent in no small part by the alliances created by fur traders’ marriage of Indian women. Certainly, this would prove to be the case at Fort Vancouver. Kinship allowed traders to pass from “outside” status to “insider” status almost instantaneously. Marriages into tribal families, especially the families of prominent leaders, opened up a world of trade opportunities to the HBC in this ethnographic context, in which familial ties insured and “inside track” when trading with the woman’s home community. (Thus, many – though by no means all, or even a majority – of the women who married into the fort community were from high-status families). Visiting the territories of the women’s tribes to seek furs, the HBC could receive special dispensation, the hospitality afforded esteemed guests, and preferential treatment relative to any HBC competitors who might seek to trade there. Native women, with their knowledge of tribal languages and territory, were an indispensable source of information to HBC traders, and the fort’s trappers appear to have followed a kind of seasonal movement between the fort and outlying territories, their paths much influenced by wives’ tribal affiliation. With women married into the HBC community, there was a greater opportunity for diplomatic relationships with the woman’s home community, and a reduced chance of violent attacks from her countrymen both at the fort and while on trading expeditions.

Interethnic marriages were clearly the norm at Fort Vancouver. Fort Vancouver was a multilingual and multiethnic community, but the households were effectively multiethnic and multilingual as well. Written accounts suggest that these women often carved out an acceptable life for themselves at Fort Vancouver, despite the sometimes shocking transition from the life of tribal communities to the life of the fort. Despite this, life at the fort also provided a source of security in an otherwise insecure environment, characterized by abrupt and generally horrifying demographic, social, and economic changes that reshaped tribal life in the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s. Certainly, as Lang (2008:106) has noted, the women of the fort “had matured during a period of breathtaking social change.” Simultaneously, these marriages gave the HBC remarkable control over the personal lives of its employees and the women they married, even long after the marriage was official. As these were strategic associations, the HBC officers also sought to place tight restrictions on its employees’ relationships with their spouses, prohibiting infidelity and attempting to regulate spousal abuse to some degree, fearing the consequences of such actions on Company security and profitability. Indeed, the Company sometimes issued severe punishments on any man whose amorous relationships put HBC trade at risk. The effects of these policies on the lives of Native women were clearly complex, with outcomes for their quality of life that were arguably both positive and negative.

Strategic Alliances

The children of these marriages helped solidify these kinship bonds, while many of them later became labor for the Company. The many Métis men who arrived at Fort Vancouver were themselves the product of such marriages, mad at other HBC and North West Company posts a generation earlier. Arriving from posts throughout northern North America, these men were descended in part from numerous First Nations from throughout eastern and central Canada – many being identified by the general ethnonym of “Cree.” Born into the fort life of their fathers and employed from youth in Company operations, few appear to have ultimately returned from the Pacific Northwest to the tribal communities of their maternal line.

The record of the Hudson’s Bay Company, as well as the North West Company, make it clear that these companies recognized the advantages of interethnic marriage as being essential to the success of their operations. Indeed, the records of these companies show considerable evidence that employees were encouraged to marry into tribes for strategic advantages. The North West Company, with its foundations in Francophone Canada, had been quite comfortably encouraging such intermarriage in the decades prior to the establishment of Fort Vancouver; the Hudson’s Bay Company, with its English roots, held a somewhat more complex view of these interethnic marriages, and Company policies on the matter could sometimes be contradictory. HBC officials in London seem to have been reluctant to condone interracial or “common-law” marriages, generally, even as their field officers recognized them as essential to the success and profitability of the Company. Amidst this internal struggle, the HBC had introduced a standardized marriage contract for use by some of its employees by 1821, representing a sort of compromise between the priggishness of London society and the practical demands of the Company’s field operations; in this contract, it was declared that the field marriage of Native women was lawful, but that the Company expected its employees to provide financial support for their spouses and to eventually “remarry” in the event that clergy became available. In the years that followed, through the time of the fort construction in 1824, the HBC made a number of subsequent proclamations reaffirming this general approach to “country” marriages.”

Despite this, marriages were sometimes arranged under considerable pressure from HBC superiors, in response to specific market opportunities or strategic objectives perceived by the Company’s leadership. Orders of this type came from as high up in the hierarchy as Governor George Simpson, himself, who seems to have made a few recommendations to Fort Vancouver’s Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin on strategic marriages that should be encouraged among fort employees. Writing in April of 1825, for example, Governor George Simpson advised McLoughlin to pressure one of his employees, John Work, to marry the daughter of a prominent chief of the Cayuse, indicating that the costs of such a union would be borne by the Company as a business expense in light of the strategic value of such a marriage. There was no indication that Work had personal interests in the daughter, but the Company made this request of him simply because Work was single and the Company needed to make inroads in their trade with the Cayuse. Simpson proposed that Work would then make frequent visits to Cayuse territory with his new wife, thus providing support to HBC brigades who were hoping to travel, safely and profitably, in Cayuse territory. It is unclear whether Work complied with the request, but Cayuse trade did intensify after this event. Still, it is clear that Indian wives of the fort were sometimes paraded along with HBC caravans, on prominent display, in order to broadcast the Company’s association with area tribes as a means of both facilitating trade and insuring the security of trading parties. The symbolic and practical value of these marriages in Native communities clearly was not lost on the officers of the HBC.

Benefits for Both Sides

NPS Photo

The advantages of interethnic marriages went both ways. As before European contact, outmarriage helped tribes to expand their kinship and trade networks, bringing prestige and commercial opportunities. The marriage of a daughter into the Fort Vancouver community was strategically advantageous for tribal communities hoping to forge trade relationships, insure their own security, and enhance the status of the village. There are a number of references to Indian families attempting to marry their daughters to prominent men associated with the fort in an effort to obtain one of these advantages. Even when young women may not have had a strong interest in marrying into the community, some evidence suggests that – like the men of the Company – they were under considerable pressure from their own people to marry and thus forge these alliances. Chinookan peoples’ wealth and status within their own communities and region seems to have been enhanced by having a daughter married into the fort community. In fact, the prominence that some villages apparently attained through their new ties with the fort sometimes became a destabilizing influence that the HBC sought to mediate, as certain villages gained almost monopolistic control over trade with the forts. George Simpson noted that, “when married or allied to the Whites they are under little restraint and in most cases gain such an ascendency that they give law to their Lords.”

While written records on the point are elusive, there is abundant evidence to demonstrate that the American Indian communities of the Pacific Northwest viewed these marriages as being an extension of traditional tribal social conventions surrounding marriage. These were exogamous, patrilocal marriages, after all, with women marrying into a polyglot community in a way that served to extend social and trade relationships. All of these elements were quite familiar to the peoples of the lower Columbia region. The tribes of the region seem to have treated the Company, or at least the Fort, as a sort of de facto village or tribe, with which they sought formal ties; with the exception of not having its own population of women to provide reciprocal outmarriages, Fort Vancouver fit neatly into this pattern.

Native Women’s Roles at Fort Vancouver

The journals and reports of the time suggest that women played numerous important roles in Fort Vancouver life. Women often participated in fur trapping expeditions, often serving in such capacities as fur dressing and food gathering and preparation. On June 29, 1836, John Kirk Townsend wrote a vaguely hyperbolic summary of native women married to Fort employees:

“She is particularly useful to her husband. As he is becoming rather infirm, she can protect him most admirably. If he wishes to cross a stream in traveling without horses or boats, she plunges in without hesitation, takes him upon her back, and lands him safely and expeditiously upon the opposite bank. She can also kill and dress an elk, run down and shoot a buffalo, or spear a salmon for her husband’s breakfast in the morning, as well as any man-servant he could employ. Added to all this, she has, in several instances, saved his life in skirmishes with Indians, at the imminent risk of her own, so that he has some reason to be proud of her.” (Townsend 1839: 179).

Not wanting to eliminate this essentially free source of labor to the HBC, fort supervisors seldom seem to have discouraged the practice. Yet, close to home, women also played a critical role in the Fort Vancouver Village community, in a way that echoed both Native and European customs. The women of this community were responsible for much of the Village cleaning and upkeep, the preparation of food, and the rearing of children. Women’s gathering of traditional foods in the vicinity of the fort sometimes provided important supplementation to the meager diet afforded by the wages of the fort’s lower-status employees. Post records indicate that Native women acquired fabric from the fort for the sewing of clothing. Their roles were as diverse as any women of their time and perhaps, being uniquely situated as they were at a cross-cultural nexus, even more so.

Inside the Fort, Out in the Village

NPS Photo

As is widely acknowledged in the historical literature, women were sequestered from many of the formal operations and affairs of the fort. Women were not present in the dining hall and the wives of the gentlemen were generally kept away from the view of visitors. Historian Hubert Howe Bancroft noted that “It was a rule of the company that the Indian wives and offspring of the officers should live in the seclusion of their own apartments, which left the officers’ mess-room to themselves and their guests.” Yet, the wives of officers held special standing in the fort, overseeing the organization of certain social events and, from the late 1830s onward, helping to host women visiting the fort. Many of these officers’ wives were Cree or Canadian Métis, arriving in the Northwest from other places within the HBC range of operations, while the employees seem to have disproportionately married local tribes. The daughters of high-ranking HBC officers and their Indian wives from elsewhere in the HBC sphere – children of an earlier era in HBC policy regarding interracial marriages – were considered especially desirable marriage partners to the ambitious young officers of the day. John McLoughlin’s wife Marguerite and James Douglas’ wife Amelia were both part Cree – Amelia being the daughter of a Chief Factor and a Cree wife; Marguerite and Amelia in many respects set the standard for Native wives at the fort, being long-term partners to their husbands, gracious hosts to visitors, and the public face of some of the officers’ charitable efforts within the Village community.

There were sharp social divides between the “ladies inside the palisade” and the women of the Village. The officers’ wives were often groomed for patrician lives, being tutored in French and English, and taught social graces considered desirable in British-American communities of the day. They were widely admired for their politeness and their attention to Anglophone values; a number of chroniclers noted that “instances of improper conduct are rare among them” (Cox 1832: 343). The “gentlemen’s wives” had to perform relatively little manual labor, though many of them were originally born into circumstances no more affluent than those of the women living in the Village. Indeed, some sources suggest that the rank of the husband appears to have had more bearing on the status of individual women at the fort than the degree of Indian ancestry, tribal affiliation, or other ethnic and racial indicators. Class appears to have been more salient than race in many respects, within the social organization of the Fort Vancouver community.

Tribal Affiliations Among Women at Fort Vancouver

NPS Photo

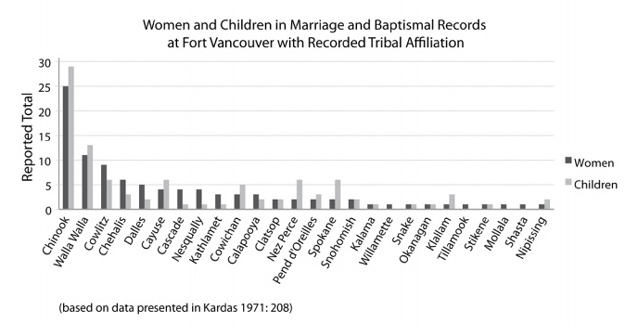

The exact identity of these women is somewhat difficult to reconstruct, This is because reliable information on the tribal affiliation of women who were part of the fort community is elusive in the written record. Church records of marriages might provide one of the few written sources of information on this point (though it is likely that tribal oral traditions may still record the affiliations of some women married at the fort). Consulting the church records is problematic, as only a minority of the fort population sought church-sanctioned marriages. “Country marriages” do not appear in available records and are very difficult to quantify. Records do suggest that marriages gradually became more church-based over the course of the 1830s and 1840s; by the 1850s, there is little reference to any further marriages of this type. Of those who did marry in church-sanctioned ceremonies, only a few identified their tribal affiliation at the time of their marriage. For example, church records demonstrate that Iroquois men were married in some 10 or 11 church-sanctioned marriages to local Native women at the fort. Yet, of these women, no more than 40% identified their tribal affiliation in a way that can be reconstructed today; in the case of the Iroquois men’s wives, the women included two Chinooks, one Kalapuya, and one Walla Walla, while the remainder do not have recorded tribal affiliations. The same issues confound the use of church baptismal records. Despite these challenges, no fewer than 26 tribal affiliations are reported for marriage and baptismal records for the Indian wives and their children.

A clear majority, if not a plurality, of the wives at Fort Vancouver were Chinookan. The women identified in the records as Dalles, Cascade, Kathlamet, Clatsop, and Kalama could have been included within the general term “Chinook” by some chroniclers’ standards, and their individual listings demonstrate that the use of the term Chinook was probably inexact. Simultaneously, the term “Chinook” appears to have denoted women from a variety of tribal communities from the coast to The Dalles, presumably with a large proportion of those women hailing from communities from the Portland Basin to the “Chinook proper” of the Columbia mouth. As was typical at this time, the term “Chinook” occasionally may have been applied to women that were not, in fact, from Chinookan communities even if they were from the greater Lower Columbia region. Other tribes represented on the list of women from this region would include the Salish-speaking Cowlitz, Chehalis, and Tillamook – together these women appear to have represented a sizeable minority within the village population. Still, it appears that these kinds of issues within the records cancel one-another out, so that we are left with an unambiguous conclusion: Chinookan women and children represented the majority of the fort resident women and children who appear in church records from 1839 through the 1850s.

Troubles with the Interethnic Marriages at Fort Vancouver

Despite the apparent harmony of these interethnic marriages, they were not without troubles. Anxiety over potential abandonment seems to have plagued many of the women of the fort. Desertions of women and children were relatively commonplace, in light of the mobility of fur traders and the regular expiration of their contracts. Men were frequently reassigned to other HBC posts, sometimes leaving their wives behind. Especially in the late 1830s and 1840s, some officers began to remarry wives from Scotland and eastern Canada, abandoning their families at that time. Governor George Simpson and Chief Trader Dugald McTavish both abandoned their half-Indian wives for British women in 1830, an event that apparently received much attention in the forts of the Company, and may have inspired similar actions among lower officers. There is also some evidence to suggest that the absence of a church-sanctioned marriage was preferred by the European and Euro-Canadian men as it allowed them to disentangle themselves and return to their home communities at the end of their service to the Company with few legal ties to bind them.

The position of the HBC on these abandonments was mixed, but McLoughlin was especially rigorous in his attempts to dissuade his employees from abandoning their wives. The HBC often allowed men to bring their mixed-race families along with them when transferred to a new post, and generally placed pressure on employees to make provisions for the care of their families in the event that they did not bring them along. The HBC did not generally subsidize the moving of family, but McLoughlin sometimes helped facilitate the moving of families between HBC posts, or arranged for abandoned women to receive payments for their support. The fort sometimes grudgingly supplied women abandoned or widowed by their employees with rations, at McLoughlin’s orders. McLoughlin went so far as to publicly flog a few individuals who refused to care for their mixed-race children and abandoned them in questionable circumstances. Moreover, marriages were sometimes arranged – in many cases by John McLoughlin himself – between women who were abandoned or widowed by Company employees and singe men working for the Company. Oral traditions of such marriages appear to be found among the progeny of some of these marriages in some Northwest tribes today.

Simultaneously, most of the men – including not only British and French-Canadian men, but also the Iroquois, Hawaiian, and Métis – widely objected to the custom of head-flattening among their wives from the lower Columbia region. As many authors have noted, “the men were universally firm on one point: they did not wish their offspring to be ‘disfigured’ by having their heads flattened, as was the Chinook custom” (Hussey 1991: 288). There are reports of abortion and infanticide by Chinookan women wishing to avoid conferring the cultural stigma of the round head on their children (Van Kirk 1980: 88; Simpson 1931: 101).

As a place where young, single women met young, single men for potential marriages, some accounts of Fort Vancouver describe the fort as a place of considerable sexual tension. This reputation, alongside the widely scorned practice of interracial marriage, would later be used by the HBC’s American and missionary critics as evidence of a general culture of licentiousness, a charge that Fort officers sometimes had to counter in their official correspondence. Stopping these liaisons, however, was nearly impossible, and the fort’s officers seem to have been somewhat resigned to romantic relationships developing that were beyond their control. Efforts to restrict contact between the employees and Native women went very badly. Indeed, there is some suggestion that the murder of John McLoughlin’s son at the HBC’s Fort Stikine was precipitated by the younger McLoughlin’s efforts to forcibly contain amorous liaisons between fort employees with Native women.

For much of the fort’s history, Native women represented the sole female presence. Jedediah Smith noted that “no English or white women was at the fort, but a great number of mixed-blood Indian extraction, such as belong to the British fur trading establishments, who were treated as wives, and the families of children taken care of accordingly.” At Fort Vancouver, as late as 1834, “no white ladies [had] yet set foot within these precincts” (Bancroft 1890s: 10). Some visitors to the fort suggest that the Native Hawaiian men were married to a number of Native Hawaiian women, but on closer examination, several of these marriages were, in fact, to American Indian women who had been misidentified; only a small number of Native Hawaiian women appear to have made the journey to the Pacific Northwest. Various sources suggest that the arrival of white women represented a symbolic break in the tradition of interracial marriage, undermining the longstanding customs of the fur trade and throwing into doubt the validity of mixed-race marriages. As historian John Hussey asserted, “when pure-blooded European women, long feared, actually arrived to take up residence…for the first time, as far as available records show – racial prejudices became a disturbing factor in Fort Vancouver society.” The first non-Native women appear to have arrived to reside at the fort in 1836; most notable among them was Jane Beaver, the wife of Anglican minister Herbert Beaver – a woman who vocally disapproved of the mixed-race community and referred to the Indians as “dirty brutes” during her 27 month stay at the fort. American women, part of missionary expeditions, began arriving at around the same time period; anticipating a life lived among indigenous people on what they considered a remote corner of the continent, these women were often pleasantly surprised by the amenities of the fort, even as they sometimes expressed distaste for multiracial families and especially the Native wives.

Still, the role of white women, specifically, in this transformation has probably been overstated. The rise of a large non-Native community in the Pacific Northwest – a community of largely American man, women, and children, who did not share the fort community’s values toward, nor dependence on, Native communities – truly brought the end to the free intermarriage between American Indian women and the fort’s men. Increasingly, as this American community grew, the men of the HBC encountered disapproval for their marriage to Native women, and mixed race families were stigmatized.

The Pressure to Remarry

Through the 1840s, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s support for these marriages wavered. Beyond the matter of race, increasing publicity in London of the prevalence of “country marriages,” unsanctioned by the church, placed the Company on the defensive. The fort’s only Anglican minister, Herbert Beaver – a bitter rival of John McLoughlin and critic of all country marriages – had been a particularly vexing source of bad publicity; nearing the conclusion of his duties at the fort, Beaver undertook a public campaign seeking to convince the Company that marriages not sanctioned by the church be punished by withholding medical attention and other critical services by fort personnel – a proposal that was soundly rejected by the Company’s leadership. Yet, under rising and vocal criticism of interethnic marriages from the American opponents of HBC interests into the early 1840s, the demand for change would not cease. Pressures mounted, within missionary and Company ranks, for men married in “country marriages” to “remarry” even long-term spouses with the involvement of clergy.

While some complied, a number of Company officers and employees very publicly refused requests to undertake remarriage ceremonies with their Native wives. Prominently, Peter Skene Ogden – who worked under McLoughlin since early in the fort’s history and served as its Chief Factor from 1849 through 1854 – refused to remarry his Nez Perce wife, Julia, considering his original marriage to be sufficient. McLoughlin complied, but did so quietly and almost clandestinely. The resistance of pressures to sanctify existing marriages by these prominent men was probably influential among the employees of the fort.

Shortly before McLoughlin’s retirement in 1846, the HBC began to discourage interethnic marriages altogether. McLoughlin protested to the Directors of the HBC: “I would wish to know…how we can prevent it in such a place as this, where the men at their work in the fields, are surrounded by Indian women.” By the 1850s, American settlers and legal institutions were generally hostile toward multiracial couples and their offspring, while ”country marriages” no longer had the legal standing that they had enjoyed under HBC jurisdictions. Ironically, following the death of Peter Skene Ogden, his wife and children found themselves socially ostracized in the region Ogden had helped settle, and – lacking both white skin or a marriage contract – were long unable to make claim to the Ogden’s estate.

Impacts

Still, the history of Fort Vancouver makes it clear: for almost the first quarter of the Pacific Northwest’s Euro-American history, the free intermarriage between white and Native people was not only tolerated, but was actively encouraged by Indian and non-Indian communities alike. This condition contradicts widely held public understandings of regional history, and stands in stark contrast to the racial and ethnic segregation that would follow the arrival of permanent American settlesrs

However, it is important to recall that the land-based fur trade had lasted for several decades before this segregation occurred. The mixed-race community was not only well-established, but it had become multi-generational. The men of these fur trade marriages were, in the first generation, European, French Canadian, Canadian Métis, Native Hawaiian or Iroquois, while the women were from a variety of Pacific Northwest tribes. As the resident mixed-race population grew, subsequent generations of fort resident adults were considered “mixed-breed” or Métis. Emerging from this multiethnic context, second-generation children of these marriages had diverse experiences. As Bancroft noted, “The daughters often marry whites, the sons seldom.” While there were many variations, the sons from these interethnic families often married back into tribal communities during the mid-19th century, while women – considered marriageable by men on the fur trade frontier – very commonly did not. The pigmentation of each individual seems to have been influential in the path they might take. With succeeding generations, and growing pressure from American settlers to divide communities racially, some branches of these families (especially the maternal lines) often became effectively “non-Indian” in identity, even as their relations became integrated into numerous tribes and identified themselves as members of those tribes in succeeding generations.

At the conclusion of exclusive HBC occupation at Fort Vancouver in the late 1840s, interethnic marriages also fostered the outmigration of many Chinookan women and their families, as their husbands were transferred between other HBC forts – especially Forts Victoria and Langley, in modern day British Columbia. Here too, some mixed-race fur trade families appear to have been integrated into the Anglo-Canadian mainstream, while others became integrated into Canadian First Nations principally through intermarriage with these groups. The Métis who did not integrate into the non-Native communities of the Northwest or move elsewhere eventually found their way into a number of tribes within the region through the mid-19th century. The exact pathways that they took were numerous, And reflect a diverse range of life experiences as individuals and families tried to find their place in a region in which multiracial peoples increasingly did not “fit.”

Last updated: February 14, 2017