Last updated: October 24, 2018

Article

Harry S Truman and the Influences of His Service in World War I

“My whole political career is based on my war service and war associates.” – Harry S Truman

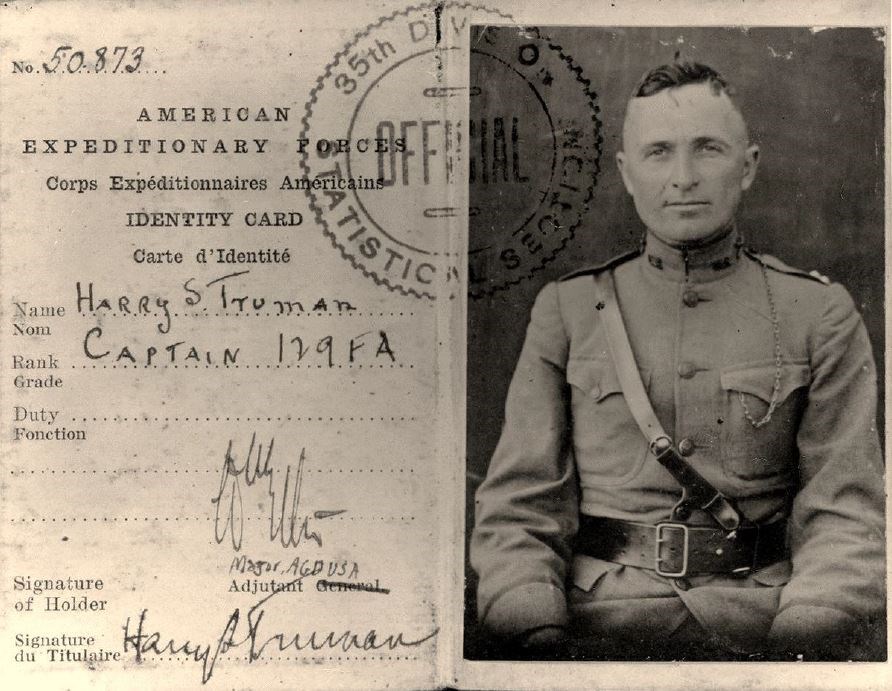

Courtesy Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

At 33, too old for the draft, Truman enlisted in the Army in 1917. Like many men, he romanticized battlefield glory. “I felt that I was a Galahad after the Grail and I’ll never forget how my love cried on my shoulder when I told her I was going. That was worth a lifetime on this earth,” Truman wrote about telling Bess Wallace, the woman who became his wife, about his enlistment.

At the time he enlisted, the Army continued two traditional practices. One, it was common for groups of local men to enlist and serve together. While this could instill instant solidarity in combat units, it could wipe out a region’s population of young men to death or casualty in war. The second practice was that units elected their officers; men they regarded as having leadership abilities.

In 1917, Truman was elected lieutenant of Battery F in the Missouri National Guard. In August, the battery was mobilized; one of six batteries in the 129th Field Artillery Regiment in the 35th Division—mostly men from the Kansas City area. Commanded by a captain, each battery had about 200 men, four French 75mm artillery guns, and personnel and equipment for a range of functions. In the eight months that the 129th trained at Camp Doniphan, at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Truman became acquainted with men from home in the other five batteries. One of these men was Jim Pendergast, Battery B, who changed the course of Truman’s life after the war.

Truman attended 2nd Corps Field Artillery School at Chatillon-sur-Seine in France and rejoined his battery in June 1918. Two days later, the regimental commander, Col. Karl Klemm, sent for Truman. Unsure about the purpose of the meeting, Truman worried, “I went over everything I’d done for the last ten days to see if I could find out what I was to be bawled out for, but could think of nothing.” He wasn’t bawled out. Klemm promoted Truman to captain and placed him in command of Battery D.

Battery D, the “Dizzy D,” was wild, undisciplined, and proud of their reputation. They were a cohesive and athletic bunch, loyal to each other. They excelled at basketball, football, baseball, and boxing. Private Vere Leigh described his fellows as “wild kids, but not dummies.” Mostly Irish and German Catholic boys, nearly all of them were graduates of the same high school and many had been to college. Truman was no dummy, either, but had been a farmer, wasn’t the least bit athletic, and had no education beyond high school.

The day Truman assumed command, he faced 200 hungover, foul-tempered, young men who were already detained to quarters for drunk and disorderly behavior. They were disdainful of authority and sized up their new commander. Private Leigh recalled, “We’d had all kinds of officers and this was just another one, you know.” Truman remembered, “I’ve been very badly frightened several times in my life and the morning of July 11, 1918 when I took over that battery was one of those times.”

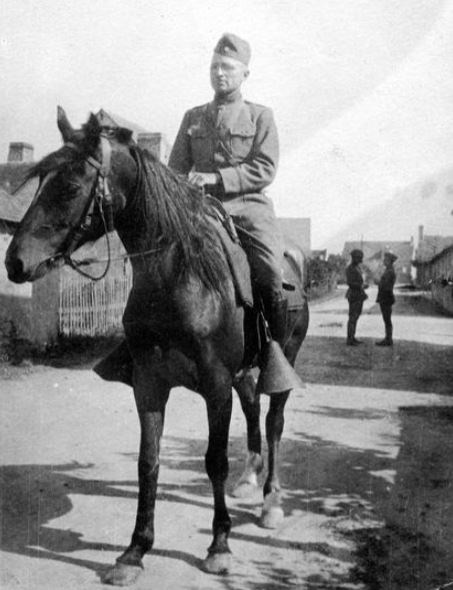

Courtesy of Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

The men of the battery were not initially impressed with their new captain. Sgt. Edward McKim remembered Truman’s “knees were knocking together.” Pvt. Floyd Ricketts thought the bespectacled Truman “gave the impression of a professor more than he did an artillery officer.” The men predicted that Truman would last no more than 90 days. When Truman dismissed the soldiers from their line-up, they responded with a disrespectful, noisy, razzing “Bronx cheer.” Later that day, the men staged a faux stampede of horses, a chaotic spectacle followed by a drunken brawl, all efforts to rattle their new captain.

The next morning, the company awoke to find a notice on the bulletin board. Half of the noncommissioned officers and most of the first class privates had been demoted. Truman told the few remaining noncoms, “I didn’t come over here to get along with you. You’ve got to get along with me. And if there are any of you who can’t, speak up right now and I’ll bust you right back now.” The men were stunned. Private Leigh remembered that as the moment they knew “we had a different ‘cat’ to do business with than we had up to that time.” Truman demanded an uncompromising discipline. “We got along,” Truman wryly characterized this period.

A rise in punishments was accompanied by an increase in rewards. It became clear that Truman genuinely cared about the men in his command and it wasn’t long before the battery came to adore Captain Truman. The food got better. Truman made sure they wrote to their mothers and sweethearts. Truman impressed his troops with his loyalty and compassion. Corporal Harry Murphy said that he knew that Truman “was going to back us to the hilt for anything that we did. All we had to do was do our duty and he was going to back us up, and he did.”

Truman privately worried about how he would behave under fire. He wrote to Bess Wallace, “I have my doubts about my bravery when heavy-explosive shells and gas attacks begin.” Battery D’s first taste of combat came in the Vosges Mountains in late August 1918. Vere Leigh remembered, “We were firing away and having a hell of a good time doing it until they began to fire back.”

Men broke and fled in what the battery later called “The Battle of Who Run.” Truman was determined to rally them.

“I got up and called them everything I knew,” he said, especially focusing on their bravery and mothers – two subjects, when disparaged, were sure to catch to Irish ears. “Pretty soon they came sneaking back.” To his men, Truman appeared fearless. Private Leigh reflected, “I don’t think he’d ever been under fire before either and it didn’t bother him a damned bit.” Harry told Bess a different story, “My greatest satisfaction is that my legs didn’t succeed in carrying me away, although they were very anxious to do it.”

Courtesy Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

At Toul Hill in France in 1918, soldiers marched for ten days through deep mud, thick as paste. Gun wagons bogged down. Rain fell. Everyone was soaked, hungry, cold, and exhausted. Undernourished horses dropped dead in stagnant muck. Worn out men reached out to steady themselves on the caissons, which was forbidden due to the extra burden it put on the already-overworked horses. A colonel noticed, and, in a fury, ordered the fatigued men to go faster and double-time up the hill. Rather than follow those orders, Truman ordered the battery off the road to rest for the remainder of the night. Somehow Truman avoided reprimand and this incident and others demonstrated that he would protect his men. In return, he earned their loyalty. “We respected him,” one soldier recalled, “because he earned it.”

After the allied victory, men headed home. They took up a collection from proceeds from an onboard crap game and purchased a loving cup to present to “Captain Harry.” It was inscribed, “Presented by the Members of Battery D in appreciation of his justice, ability and leadership.”

Truman’s war leadership paid dividends in civilian life. After returning home in 1919, Harry married Bess and opened a haberdashery in Kansas City in partnership with Eddie Jacobson, a sergeant in Battery F, whom Truman had met at Camp Doniphan. The shop did well at first, but by summer 1921, it was struggling in a post-war depression. That summer, Jim Pendergast from Battery B, and his father, Mike, paid Truman a visit. Jim’s uncle and Mike’s brother, Tom Pendergast, was the Democratic political boss of Jackson County. The Pendergasts’ mission was to gauge Truman’s interest in a job in politics. With the store failing, (it would close in early 1922) Harry was interested.

Jackson County, Missouri was administered by a panel of three “judges”—elected officers comparable to county commissioners. The court had a presiding judge, elected at large, and an eastern and western district judge, elected from their districts. The Pendergasts sought to nominate Truman for eastern district judge.

From their war experience, Jim Pendergast saw first-hand Truman’s integrity, leadership, and loyalty. Truman was a war hero. The US suffered 53,402 combat deaths in World War I, many of them from the 129th Field Artillery. Under Truman’s command, Battery D had no combat deaths. Well known in the county and an active and admired member in the Masons and other fraternal organizations, Truman had also amassed a significant base of veterans who were fiercely dedicated to him.

The Pendergast political machine backed candidates who could win and Truman’s World War I connections virtually guaranteed a victory. Truman had connections to roughly 1,000 local men from all six batteries of the 129th and they, along with their friends and families, were more than willing to cast votes for Captain Harry. Many former soldiers had become influential business and government leaders. The veterans campaigned and raised money for Truman.

Courtesy Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

Veterans formed the core of Truman’s support in his Jackson County campaigns for eastern district judge and later, presiding judge. Work with veterans’ organizations provided statewide contacts for his 1934 Senate campaign. During this first Senate term, he adopted the American Legion’s positions on defense as his own. Truman served on Senate committees responsible for military appropriations and policy. His knowledge of the military contributed to the success of the Truman Committee, which investigated defense expenditures during World War II and conferred a national reputation. That led to a nomination for vice president in 1944, which led to the presidency. Seventy nine of the 138 surviving members of Battery D marched with Truman in his 1949 presidential inaugural parade. Former Private Floyd Ricketts later said, “Truman told me personally, many times afterwards, that if it hadn’t been for the help of our organization, he doubted that he could have been elected.” From lowly private to Commander in Chief, Harry Truman probably saw the military from more perspectives than any other president.

Corporal Harry Murphy reflected, “I think of Battery D as the most mischievous, unpredictable, and difficult to handle unit…but when the chips were down, to the man, they were a fine bunch of soldiers. I am proud to have been one of them. Captain Truman, who did successfully handle this outfit, deserved to be the President of the United States.”