Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

From the Great Migration to Boston's Charlestown Navy Yard

African American communities across the country experienced significant changes in the period between the US Civil War and World War I. Black southerners grew tired and frustrated of the discrimination and growing inequality in their towns. While some stayed and fought against this oppression, others made their way to northern cities full of hope. They hoped to flee Jim Crow laws, to find new economic opportunities, to establish new and better lives for themselves and their families. This mass exodus from the South became known as the Great Migration.

While most people associate cities such as Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles with the Great Migration, Boston also served as a final destination for many Black migrants. In Boston, African Americans tried to begin afresh, joining the local Black community and searching for jobs offered in the city. Some of them found the answer to their search for economic opportunities at the Charlestown Navy Yard.

Chicago Defender, September 2, 1916

Great Migration

Scholars frequently associate the beginning of the Great Migration with the advent of World War I. While accurate, some African Americans had already moved north prior to the war.[1] Author of the award winning work The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, Isabel Wilkerson describes the evolution of the Great Migration from the 1870s to the 1910s. First, a "trickle of brave souls" left for the North after the Civil War, followed by a "stream after Jim Crow laws closed in on Blacks in the South in the 1890s." Finally "a river, uncontrolled and uncontrollable" of Black southerners migrated north during the decade of World War I.[2]

The reasons African Americans left the South varied. Scholars frequently debate these push and pull factors that sparked the Great Migration.[3] Some migrants felt pulled by economic reasons. They heard of the growth of northern cities and industries that desperately needed to hire individuals in order to keep up with the expanding economy. Some of these industries sent labor agents south to recruit workers.[4] Black newspapers, such as the Chicago Defender, advertised jobs and the benefits of migrating to northern cities.[5] African Americans also heard from family members, friends, and neighbors who had already made the move north about new opportunities and their better lives.

Meanwhile, African Americans in cities and towns across the South faced competition for jobs that drove down wages.[6] This especially affected laborers in the tobacco, cotton, iron, and related industries; on average, workers in the South earned three-fourths the wage of workers in northern states.[7] Black skilled and semi-skilled workers, such as blacksmiths and carpenters, recognized they could make more money in the North, even if they found work as unskilled laborers.[8] However, this willingness to accept lower-skilled and waged jobs led to employers exploiting southern Black migrants, creating a large economic gap between Black and White workers.[9]

Other Black migrants fled the South due to the heightening racial terror. They felt the Jim Crow laws strengthening around them as White southern leaders tried to solidify African Americans' place as second-class citizens.[10] In addition to these laws, southern Whites attempted to enforce this racial hierarchy with brutal mob violence. Between 1877 and 1950, over 4,000 racial terror lynchings took place throughout the country, mainly in southern communities.[11] Due to an intense fear for their lives, Isabel Wilkerson likens these migrants to

refugees from famine, war, and genocide in other parts of the world, where oppressed people… go great distances, journey across rivers, deserts, and oceans or as far as it takes to reach safety with the hope that life will be better wherever they land.[12]

Some Black southerners bravely lived within this system set before them, finding ways to resist and fight back; however, others took a different path to escape the discrimination and terror in the South.

Boston Pictorial Archive, Boston Public Library.

Great Migration and Boston

When considering the history of the Great Migration, most scholars discuss this migration’s influence on cities such as New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. These cities experienced sharp increases in their Black populations during the first half of the 20th century. Between 1910 and 1940, 1.5 million Black Americans left the South, and between 1940 and 1950 an additional 1.5 million more moved, dispersing themselves among cities in the North, Midwest, and West.[13]

Thousands of these migrants settled in Boston. Over the first few decades of the 20th century, Boston's Black population slowly grew from 11,591 people in 1900 to 51,568 people in 1950.

| City | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston | 11,591 | 13,564 | 16,350 | 20,574 | 23,679 | 51,568 |

| New York | 60,666 | 91,709 | 152,467 | 327,706 | 458,444 | 820,227 |

| Chicago | 30,150 | 44,103 | 109,458 | 233,903 | 277,731 | 586,598 |

| Los Angeles | 2,131 | 7,599 | 15,579 | 38,894 | 63,774 | 104,402 |

Migrants traveling to Boston frequently took one of the trains heading up the East Coast. They began in southern states such as Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia and stopped in several major northern cities, including Philadelphia, New York, and Boston.[14] These trains served as one of the three main routes traveled by southern Black migrants.[15]

Considering this path helps answer the question why Boston received a smaller influx of Black southerners during the Great Migration. Some migrants may have ended their journeys at one of these other northern cities prior to Boston.[16] Additionally, the journey cost African Americans weeks of wages, and frequently these individuals sold everything they owned prior to making the trip.[17] Therefore, the migrants who made the trip to Boston must have had a strong desire to continue north, as Wilkerson states, “the greater the obstacles and the farther the distance traveled, the more ambitious the migrants.”[18]

When they arrived in Boston, many southern Black migrants moved to Roxbury. According to Wilkerson, Roxbury served as a destination for many migrants from Norfolk, Virginia.[19] Other migrants from across the South may have traveled to Boston to follow their relatives, friends, or former neighbors. Since this Boston neighborhood had a well established Black community, southern migrants received support from local churches and groups to establish their new life and form their own close-knit communities.[20]

As southern African Americans settled in Boston, they searched for employment opportunities throughout the city. Organizations such as the Boston Branch of the NAACP and the Boston Urban League frequently provided programs for new southern migrants and helped them find jobs.[21] Looking at the marginal increase of Boston’s Black population during the first couple decades of the Great Migration in the 1910s and 1920s, historian Mark Robert Schneider argues Black southerners may have struggled to find jobs at this time due to the conservative politics of the city. The conservative policies limited economic growth, which led to fewer economic opportunities for Black migrants, possibly resulting in fewer migrants traveling to Boston over these decades.[22]

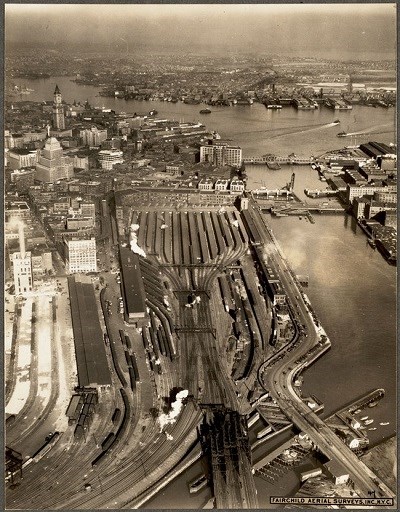

National Archives and Records Administration

Charlestown Navy Yard

World War II likely changed the job opportunities that awaited migrants arriving in Boston. While some Black southerners found jobs in the railroad industry or the domestic sphere, others responded to the defense industry's need for a strong workforce. With the onset of World War II, the Charlestown Navy Yard increased its shipbuilding production, which required more civilian workers. With this knowledge, southern Black migrants may have seen the Navy Yard as a promising place for employment. This especially held true for African Americans working as blacksmiths or shipbuilders in the South, who possibly saw the Charlestown Navy Yard as a place they could utilize their skills and earn good wages.[23]

Locating records regarding the number of African American workers at the Navy Yard has proven difficult. Some records during World War II group all minorities together, making it impossible to track down whether African American workers came from the South. One available record, a Charlestown Navy Yard report submitted to the Navy Department, identified just over 2,000 Black workers at the Yard in November of 1943, out of 47,000 total workers.[24] While only a small percentage of the entire workforce, these workers surely played an essential role in the Navy Yard's contribution to the war effort.

Newspapers, census records, oral histories, and other documents further link the Great Migration to the Charlestown Navy Yard. Boston census records from the 1940s identify southern African American workers at the Navy Yard a couple of years prior to the war. Occasional mentions in newspapers or oral histories provide anecdotal evidence to this connection. For example, Barbara Tuttle Green, a White woman who worked as a welder at the Navy Yard in 1943, noted in her oral history that she met a lot of southern Black workers who came to the Navy Yard since they heard it was hiring and offering good wages.[25] She said:

I talked to one girl, and I guess they were really mistreated terribly down there by the whites. She said that one man was dragged around town on the back end of a car, because he had been seen just talking to a white girl. I think that is why a lot of them, when they did come up here to work, they stayed here, because they were not mistreated.[26]

While Boston did not receive the same influx of African American southern migrants as other cities, this mass migration still affected Boston. Thousands of Black southerners came to Boston frustrated with the inequality and discrimination they experienced in the South. In this new city, they hoped to find social equality and economic stability, possibly through a job at the Charlestown Navy Yard. And, more importantly, they sought a place that would provide a better social climate than what they faced in the South.[27] While we can debate whether Boston, or any other city, provided migrants with the answers they sought, Isabel Wilkerson calls us to instead consider

how [southern Black migrants] summoned the courage to leave in the first place or how they found the will to press beyond the forces against them and the faith in a country that had rejected them for so long. By their actions, they did not dream the American Dream, they willed it into being by a definition of their own choosing.[28]

Footnotes

[1] Carole Marks, “Black Workers and the Great Migration North,” Phylon 46, no. 2(2nd Qtr., 1985), 149.

[2] Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010), 161.

[3] Marks, “Black Workers and the Great Migration North,” 148.

[4] Marks, “Black Workers and the Great Migration North,”155.

[5] Marks, “Black Workers and the Great Migration North,”155.

[6] Marks, “Black Workers and the Great Migration North,” 151.

[7] Marks, “Black Workers and the Great Migration North,” 151-152.

[8] Marks, “Black Workers and the Great Migration North,” 152.; Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 159.

[9] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 160.

[10] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 40.

[11] Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, 3rd edition, 2017, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/.

[12] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 179.

[13] Thomas H. O’Connor, The Hub: Boston Past And Present, (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2001), 236. “The Second Great Migration.” The African-American Migration Experience, New York Public Library, 2005, http://www.inmotionaame.org/migrations/landing.cfm?migration=9; “The Great Migration, 1910-1970,” United States Census Bureau, September 12, 2012, https://www.census.gov/dataviz/visualizations/020/.

[14] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 178; In her analysis, Isabel Wilkerson defines three routes migrants followed to travel to different regions in the country. Migrants from the Southeast journeyed to cities in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. Migrants from Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, and Arkansas traveled to northern cities such as Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, and Pittsburgh. Finally, migrants from Texas and Louisiana typically made their way to the West Coast.

[15] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 178.

[16] James Oliver Horton, “Blacks in Antebellum Boston: The Migrant and the Community, an Analysis of Adaptation,” in Making a Living: The Work Experience of African Americans in New England Selected Readings, edited by Robert Hall and Michael M. Harvey, (Boston: New England Foundation for the Humanities, 1995), 312-318.

[17] Marks, “Black Workers and the Great Migration North,” 156.; Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 178.

[18] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 261.

[19] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 243.

[20] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 243, 271.

[21] Robert C. Hayden, “A Historical Overview of Poverty among Blacks in Boston, 1850-1990,” Trotter Review 17, no. 1 (September 2007), 137, https://archive.org/details/trotterreview171willi/page/137

[22] Mark R. Schneider, Boston Confronts Jim Crow: 1890-1920 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997), 21.

[23] Marks, “Black Workers and the Great Migration North,” 151.

[24] Data on Negro Employment to be Submitted as of 30 November 1943; Appointment and Employment (Civilian), Oct. 1943; Boston Navy Yard Commandant’s Office General Correspondence P13-10 to P14-2, Box 70; Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments, 1784 - 2000, Record Group 181; National Archives at Boston.

[25] Barbara Tuttle Green, interviewed by Francy K. Bockoven, Oral History, December 7, 1977, Boston National Historical Park, 4.

[26] Green, Oral History, Boston National Historical Park, 14.

[27] Schneider, Boston Confronts Jim Crow: 1890-1920, 4-7.

[28] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 538.