Last updated: March 6, 2020

Article

The Fort Vancouver Community

NPS Photo

Excerpted and adapted from An Ethnohistorical Overview of Groups with Ties to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, by Douglas Deur. Contact us for a PDF of the full report.

In 1778, Captain James Cook first sailed along the Northwest Coast, where he traded with coastal tribes, and learned that furs could be exchanged in China for spices, silks, teas, and other goods that sold at a premium in the European and American markets. Since receiving reports of this voyage, the European world had been in a rush to make claims to the resource wealth of the Northwest Coast of America. Perhaps no entity was as well prepared to enter the Northwest and profit from its fur wealth than the Hudson’s Bay Company. The arrival of the HBC on this coast was the realization of roughly 150 years of Company ambition, initiated when the Company was incorporated under a British royal charter in 1670 as “The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay,” with the aim of bringing the furs of North America to European markets for a considerable profit. Since its inception, the Company’s operations had spread across the expanding frontiers of British North America. Their arrival on the legendarily fur-rich Northwest Coast was a move of great strategic importance to the Company.

Optimism about the Company’s future abounded, and the value of shares in the Company soared in the early years of Fort Vancouver’s operations. The rise of the Company’s fortunes in this distant corner of North America temporarily gave credibility to British territorial claims to the Oregon country and gave hope to those who envisioned British colonization of the region. For both of these ambitions – pecuniary and nationalistic – to be realized however, the Crown and the Company recognized that they would have to proceed cautiously and strategically with the large resident population of Indians living there. Certainly, a century and a half of experience on the commercial frontiers of North America had well prepared the HBC for this task of entering the Northwest and exploring the region’s fur wealth and Native labor.

Yet the resident peoples of the Pacific Northwest, with perhaps a millennia of experience as traders, were also well equipped for the encounter in many respects. The very earliest accounts of explorers entering the lower Columbia River mention an active trade and estimable skills of negotiation among the river’s indigenous peoples. Arriving in 1792, the crews of George Vancouver’s ship were astonished to find themselves in the presence of such skilled traders:

“One very large Canoe with about five & twenty Indians in her, (the second we saw since we entered the River) came along side and brought some Salmon which we eagerly bought of them on reasonable terms; they also brought two or 3 Otter Skins for sale and seem’d to know the value of them very well.”

Almost every ship that followed attracted large flotillas of canoes bearing furs and other items that were eagerly exchanged for the trade goods of the European world.

Arriving on the lower Columbia, the Hudson’s Bay Company recognized that – in order for their enterprise to succeed – the Company would require not only a peaceful coexistence with the Indians of the Northwest, but also the active involvement of these Indians in all aspects of their organization. Certainly, the Company was a formidable presence; at its peak, Eugene Duflot de Mofras would marvel that “this powerful organization controls throughout its vast territories in North America 200 forts or posts, 12,000 white inhabitants, nineteen-twentieths of whom are French-Canadians, and 200,000 Indians.: Yet, when the Company arrived in the Northwest in the 1820s, it was as a small and strategically disadvantaged minority in a densely settled corner of the continent. Their efforts to achieve “a complete control over the Indians” in their commercial operations were understood to be a practical impossibility. Instead, the Company sought to employ a combination of incentives and punishments, calculated to open the pathways of commerce by securing the loyalties of the Indians and reducing their strategic threat. Foremost among the strategies employed toward this end was the development of commercial operations that created economic incentives for Indian trade and, in time, a growing Indian dependence on trade goods. As Fort Vancouver’s Chief Factor John McLoughlin acknowledged, “it is proved by experience, that the only way to gain the confidence of Indians and influence over them, is by having Establishments on their lands.” The HBC had arrived in remote frontiers and developed trade relationships numerous times throughout North America, and in the Pacific Northwest they applied their considerable experience to good effect. Also key to the establishment of the Company’s influence among the Indians was a policy of encouraging intermarriage of its employees with Native women, thus giving the company, in essence, a type of kinship status with the region’s tribes that insured preferential treatment and eliminated barriers to trade.

From North West Company to Hudson’s Bay Company

The multi-ethnic fur trading frontier had been moving ever westward for roughly a century and a half prior to its arrival on the Northwest Coast. Moreover, the fur trade was already transforming the region long before the construction of Fort Vancouver. By the time Fort Vancouver was operating, the Indians of the lower Columbia River had roughly 33 years of trading experience with non-Indians, including almost 15 years of operations at Fort George on the Columbia River estuary. Fort George, established by the New York-based tycoon John Jacob Astor in 1811, was in the management of the Montreal-based North West Company from 1813 until 1821, when that Company was acquired in a merger with the Hudson’s Bay Company and its assets absorbed into HBC operations. The acquisition of the North West Company not long before the construction of Fort Vancouver had a number of effects on HBC operations.

The North West Company, with its roots in Francophone North America, arguably had a more egalitarian and decentralized management style than the British-based HBC, with the former’s employees freely intermarrying with Native women and making inroads within a wide constellation of Indian communities throughout the region. When the Hudson’s Bay Company consolidated with, and effectively absorbed, the operations of the North West Company, they inherited the legacy of the North West Company’s relationships with tribes throughout the Northwest. Fortunately for the HBC, in its brief time in the region, the North West Company had maintained positive relationships with tribes throughout a wide trade network, including coastal tribes as well as some of the tribes, such as the Yakama, who effectively controlled access to vast portions of the Northwestern interior.

Though there was a certain clash of styles apparent at the early Fort Vancouver resulting from the integration of the two companies, the North West Company's considerable effectiveness at building inroads in the region would yield great dividends to the HBC in the Fort Vancouver years.

The Shift to Fort Vancouver

The arrival of the HBC heralded a time of significant change in the Pacific Northwest fur trade. Certainly, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s decision to move its operations from Fort George, on the Columbia River estuary, to Fort Vancouver – roughly 100 river miles inland – was not made lightly.

The changing geography of the fur trade, and the changing relationships with area tribes, were critical to the decision to make this move. The HBC was undertaking a restructuring of the Columbia Department following Governor George Simpson’s tour of the region in 1824-1825, in order to make operations more efficient and to adapt to the changing realities of the Northwestern fur trade. The considerable effort required to relocate from the existing facilities at Fort George, on the Columbia estuary, to construct a fort anew at the inland site of Fort Vancouver, suggests the importance of this move in achieving the larger goals of the HBC as part of this restructuring.

Critical among these goals, the situation of Fort Vancouver was chosen for its strategic location relative to the developing fur trade of the Northwestern interior. By 1824, the sea otter population of the outer coast had been largely exhausted, and the supply of locally available terrestrial furbearers on the Columbia estuary and adjacent coastline was in abrupt decline. The land-based fur trade was quickly eclipsing the ship-based maritime fur trade and the HBC leadership looked eagerly toward the Northwestern interior as a source of beaver and other furs. The Snake Country expeditions, being initiated concurrently with the planning for the new fort, suggested the potentials of the interior trade to HBC officers. The shift from a sea-based to a land-based fur trade brought a significant increase in the extent of interaction between white traders and the resident tribal communities; interethnic fur trade relationships became more constant, and much hastened the pace of cultural, economic, and demographic transformation within those communities. By necessity, the HBC expanded its commercial operations into a widening sphere of trade networks into the Northwestern interior, and Fort Vancouver sat at an advantageous intersection of the principal avenues of tribal trade running east-west along the Columbia River and north-south along the Willamette Valley and Puget-Cowlitz Lowland.

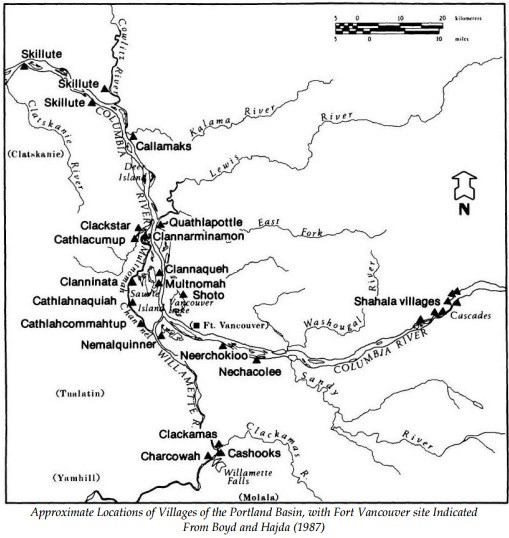

The location of the fort also, no doubt, took into consideration the geographic distribution of area tribes. There were clear advantages to being located in a boundary zone, in a place that was densely settled yet a site that was, itself, largely unoccupied. The absence of a major village in this attractive site was noteworthy, and perhaps reflects the absence of especially accessible fishing or marsh resource procurement areas in the immediate vicinity of the fort. Yet this neighborhood had an abundance of large villages, their residents by and large eager to participate in the fur trade as intermediaries to the larger network of Pacific Northwest tribes. The situation of the fort was conducive to the expanding ambitions of the HBC within the region and served the Company very well in the decades that followed.

The site for Fort Vancouver was clearly chosen for its agricultural potential. At Fort George, traders had been largely dependent on Indian trade to acquire the bulk of their food supply. This created dependence on local tribes, particularly the Chinook proper and Clatsop, thus undercutting not only the fort’s security, but also the negotiating powers of its traders who bargained with these tribes for each pelt arriving at the fort.

At Fort Vancouver, in contrast, the land was relatively level, cleared by an apparently long history of aboriginal burning, and made fertile by the combined effects of burning and freshets along the Columbia River. With its verdant fields and its southern exposure, the site had agricultural potentials unsurpassed, arguably, along the entire lower Columbia River shoreline. Certainly, the site had other virtues: access to deep water for the mooring of ships, and defensive potentials afforded by its commanding views, though this could be found in a number of other locations; so too, the fort was located on the north bank of the river, based on expectations that the south side of the river might fall into American control. Nonetheless, the agricultural value of this land was perhaps the site’s most distinctive strategic asset and set it apart from other sites along the river.

NPS Photo

Forming a Fur Trade Community

During the period of HBC occupation (1824-1860), there were arguably three primary tribal communities to be found at this site. The first consisted of the resident tribes living near the fort, while the second consisted of visiting tribes and tribal members who gathered at the fort to trade and socialize. The third consisted of the resident community living in the fort and the “Village” community that sat just outside its palisades; this diverse population consisted of men from throughout the HBC sphere of influence – Iroquois, Métis, Native Hawaiian, French-Canadian, British, and otherwise – who were married to Indian and Métis women from throughout northern and western North America, mostly from Pacific Northwest tribes.

This three-part divisions of the Native peoples associated with the fort serves mostly as a way of organizing our thinking about the fort’s relationships with Native communities, but in reality these categories were indefinite; each group appears to have blurred somewhat into the other, with kinship networks uniting the residents of the Village with neighboring tribes, and uniting both of these populations with the steady progression of tribal visitors from more distant locations. The HBC relationships with each of these three populations were critical to the success of the enterprise at Fort Vancouver.

Navigating Trade Networks and Mutual Interests

The Native peoples of the lower Columbia region already possessed a sprawling and highly successful trade network when the fort was constructed in 1824. Rather than attempting to supplant it, the Hudson’s Bay Company determined to work their way into these existing networks as the foundation of their fur trading enterprise. Such an approach was typical of HBC operations throughout North America and, in fact, was common to many British chartered corporations operating in colonial contexts worldwide. Hiring Chinookan and Cowlitz peoples in their traditional roles as middlemen, the Company almost immediately gained access to the full spectrum of tribal trading partners, extending for hundreds of miles, north, south, and east of the fort. The Chinook and Cowlitz were not only willing, but downright enthusiastic participants in this arrangement. As many authors have noted, this only served to augment the existing wealth and importance of lower Columbia peoples. They worked hard to maintain their monopolistic relationship with the fort. As George Simpson observed in 1830,

“Nearly all the furs got now at this place pass through the hands of three chiefs or principal Indians viz. Concomeley King or Chief of the Chinooks at Point George, Casseno Chief of a tribe or band settled nearly opposite from Belle Vue Point [the plain where the reconstructed Fort Vancouver is now located] and Schannaway (Scanewa) the Cowlitch [Cowlitz] Chief whose track from the borders of Puget Sound strikes on the Columbia near to Belle vue Point; the first is much attached to us and will follow wherever we go…The Chinooks [are] keen traders and through their hands nearly the whole of our Furs pass, indeed so tenacious are they of this Monopoly that their jealousy would carry them the length of pillaging or even murdering strangers who come to the Establishment if we did not protect them. To the other tribes on the Coast they represent us as Cannibals and every thing that is bad in order to deter them from visiting the fort.”

Yet this monopoly of Chinookan and Cowlitz leaders over access to the fort could be a problem for the Company. In its early years, the HBC had a nagging dependence on Chinook canoes, and – prior to relocating to Fort Vancouver – food. Also, in these early years, the HBC was still dependent on the Indian community for a tremendous amount of geographical knowledge, regarding the distribution of tribal territories, fur-bearing animals, waterways and land routes, and so on.

Beyond these matters, of course, the Chinook and Cowlitz control over access to furs gave them significant influence over the pricing of furs and other merchandise through the 1820s. Many of the major initiatives undertaken in the early years of Fort Vancouver that might seem peripheral to the immediacies of the fur trade – such as the development of major agricultural, boatbuilding, and milling facilities in accusation with the fort – might be interpreted as efforts to overcome dependence on the tribal monopolies of the lower Columbia Indians. Over time, as the Company became more established, it worked to overcome the monopolies of these lower Columbia tribal leaders by hiring groups from farther afield as guides and laborers, and seems to have sometimes worked to exasperate existing divisions between tribal groups so as to keep fur prices competitive.

In fact, the HBC and the Indian communities of the lower Columbia River seem to have jockeyed to maintain monopolistic control over one-another’s trade interests through the 1820s. The HBC sought to regulate Indians’ access to outside, non-Native interests, just as Indians sought to regulate HBC contact with interior tribes – both seeking to monopolize the commercial interests of the other side. The HBC was very eager to maintain its own monopolistic control on the trade with European and American interests. American vessels and traders were a constant source of annoyance to Fort Vancouver officers. (However, HBC rapport with tribes, developed through mutually beneficial trade as well as extensive intermarriage, gave them a distinct advantage compared to their loosely organized American counterparts – especially in interior areas such as the ‘Snake Country’ where Americans seldom succeeded in making inroads.) Still, the constant presence of a modest number of competitors, principally American ship-borne traders, and later land-based operations, kept trade competitive. The correspondence of the Company also makes reference to having to lower prices and include cheap goods to compete with traders operating outside the fort. As McLoughlin often noted in his correspondence, strict controls also were maintained over even the smallest transactions between Indians and British subjects in the region: “No British subject could trade with the Indians without a License…no person in the service was allowed to trade or even receive presents from the Indians,” he wrote in 1829. Using cautionary tales of Indian visits to ships gone awry, McLoughlin attempted to keep even the crews of his own ships from having exchanges of any kind with the tribes that might route goods around the fort and undermine the Company’s competitive position.

NPS Photo by Junelle Lawry

NPS Photo by Sarah Silliman

Fort Vancouver’s Indian Trade Shop

The hub of this trade inside Fort Vancouver was the Indian Trade Shop. This shop, located within the fort’s palisades, served as a storehouse for furs being purchased from local tribes, as well as a storehouse of goods – from beads to tools to rifles – that were used in exchange for these furs. The building was also commonly called the “Indian Hall,” the “Indian Shop,” the “Indian Store,” the “Fur House,” and other variations in Company records. It was also sometimes called the “Missionary Store” as the missionaries were allowed to store their property there, and a hospital and dispensary were sometimes operated out of the same building, occasionally servicing Indian visitors in addition to Company employees. More than one structure served this function over the life of the fort, but the store appears to have consistently been located within the palisades.

Indians were often employed at the Indian Trade Shop, and it appears that employees were chosen for this store with strategic attention to how these individuals – and their tribal affiliations – would be perceived by visiting Indian traders.

There, they engaged in a lively exchange in such items as beads and other adornments, Hudson’s Bay Company blankets, fabric, metal tools, guns and ammunition – all priced so as to retrieve a consistent and predictable profit. Trade goods fit nicely into preexisting patterns of trade in goods within the lower Columbia region, which had long been a center of exchange for exotic merchandise from throughout western North America. Yet, for those tribal communities that were well connected to the fort, trade goods rapidly transformed the material culture of the lower Columbia, and brought new efficiencies to hunting, wood carving, and other traditional tasks.

Changing Power Dynamics

Yet the presence of the fort transformed much more than the material culture of the lower Columbia region. The trade introduced by the fort was highly lucrative and transformed relationships within and between tribes in profound ways. There was good reason for the Chinooks and Cowlitz wishing to maintain their trade monopolies with the fort. The wealth and status of chiefs along the Lower Columbia in the early years of the fort was elevated by the HBC policy of seeking to work through leaders rather than through larger groups to organize fur trade exchanges. Through the 1820s, there was a consolidation of village sites and wealth along the Columbia River, as a small number of chiefs – buoyed by their control over fur trade wealth – ascended to newly elevated roles in the region. Chiefs such as Concomly, Casino, and Scanewa became regionally dominant in a way that may have been difficult to achieve only a generation before.

The Lower Chinook chief, Concomly, was perhaps the most widely celebrated beneficiary of these relationships. During Concomly’s visits to Fort Vancouver, he was reported to be preceded by 300 slaves and, as reported by deSmet, “he used to carpet the ground that he had to traverse, from the main entrance of the fort to the governor’s door, several hundred feet, with beaver and otter skins.” This demonstration of his tremendous wealth and power had multiple audiences, both Native and non-Native – helping to inspire loyalty among his own people and commercial enthusiasms among the Company’s officers, thereby to insure the continued expansion of his influence. While such rising affluence sometimes had destabilizing effects in the balance of power between Indian communities, which the HBC sometimes sought to counterbalance, it was generally in the Company’s interest to have these leaders maintaining positions of great prominence.

The fort and the lower Columbia tribal leadership quickly became mutually interdependent. So strong were the bonds between the fort and the neighboring tribal communities that one attempted attack on the fort – precipitated, incidentally, by Wascos protesting HBC proposals to remove a trading post out of their territory – was repelled principally through the strategic intervention of Chief Casino. (Indeed, relocating a fur trading post generally was considered dangerous by the HBC due to potentially violent protests from the tribes from whose territory the fort was to be removed and among whom the fort had fostered commercial interdependence.) When a fire threatened to burn down Fort Vancouver in the 1840s, it was the immediate response of Indian people living nearby who were critical to saving the fort. The protection of the fort was absolutely in the interests of the Chinook and Cowlitz leaders who had the strongest commercial ties there. By forging mutual economic bonds, the HBC had effectively insured the fort’s security.

A Diverse Community

Trade at Fort Vancouver had demographic consequences through the 1820s as well, bringing a growing number of Indians to settlements in close proximity to the fort. The attraction of the fort in its first few years of operation was apparently sufficient that the permanent populations of these villages grew noticeably. In some cases, populations with scattered territorial associations, including the Multnomah, Cascades, and Clackamas, moved within their traditional use areas to be situated more closely to the fort. These longstanding villages close to the fort hosted many of the temporary tribal visitors to the fort, while others stayed in temporary encampments upon their arrival at the fort:

“This post is only a short distance from the Columbia River, on a plain made valuable in its entirety by agriculture. The engages of the Company have their habitations on this plain, toward the river, whose bank is lined with the huts of natives who come there from every direction to trade the fruits of their hunting”

- Fathers Francois Blanchet and Modeste Demers

Those who had relations in the Village of employees and their families sitting just beyond the palisades might stay in their homes or camp near the Village too. While the written record is sometimes unclear on this point, it appears that the multi-tribal gatherings in villages and encampments by the fort provided opportunities for social activities, gambling, horse racing, and other activities. Ceremonial activities are also described, taking place in encampments a short distance from the fort.

Thus, many observers noted of Fort Vancouver that “It was a place of great activity, surrounded by many tribes who spoke different languages.” While echoing traditional multi-tribal gatherings that predated the fort, these gatherings brought together a novel breadth of tribes, and facilitated the expansion of social, economic, cultural, and kindship ties that linked tribes from throughout the Pacific Northwest. Quickly becoming the center node of a trade network spanning the entire region, with Company employees hailing from throughout British North America, the fort thus became, perhaps, the foremost center of linguistic and cultural diversity in the Northwest. Horatio Hale’s brief comments on the languages used in the fort are illuminating in this regard:

“At this establishment five languages are spoken by about five hundred persons – namely, the English, the Canadian French, the Tshinuk, the Cree, of Knisteneau, and the Hawaiian…the Cree is the language spoken in the families of many officers and men belonging to the Hudson’s Bay Company, who have married half-breed wives at the posts east of the Rocky Mountains. The Hawaiian is in use among about a hundred natives of the Sandwich Islands who are employed as laborours [sic] about the fort. Besides these five languages there are many others – the Tsihailish [Chehalis], Walawala [Walla Walla], Kalapuya, Naskwale [Nisqually], &c. – which are daily heard from natives who visit the fort for the purpose of trading.”

Hale mentions only nine languages in this passage, but his list easily could have been expanded to perhaps thirty or more languages that were frequently heard among the traders of Fort Vancouver. The fact that Fort Vancouver was such a gathering place for tribal people originating throughout the Pacific Northwest made it an especially rich venue for the observation of tribes and their customs. Writing in 1841, Samuel Parker noted that he was able to record considerable detail about the tribes of the region while simply staying at the fort:

“As this is the principal trading post of the company, west of the Rocky Mountains, it may be expected, that many Indians from different parts of the country for considerable distance around, will be seen here during the winter, and more information may be obtained of their character and condition than in any other course I could pursue. Here also traders from different stations west of the mountains will come in for new supplies, of whose personal acquaintance with Indians I may avail myself.”

Many famous early authors on Pacific Norwest tribal history, from George Gibbs to Paul Kane, seem to have followed this example and used the fort as a base of operations for their investigations of the region’s many Native peoples.

The diversity of the Fort Vancouver workforce was augmented considerably by its proximity to both the Columbia Cascades and Willamette Falls. While the former was much larger, both of these natural features were significant multi-tribal fishing stations, where villages and temporary encampments housed both resident peoples and numerous visiting tribal populations in season. The visitors to these fishing stations arrived from numerous territories, from both inland and downstream locations, so that during the peak fishing season these falls became sprawling multi-lingual, multi-tribal encampments. From a time before the construction of Fort Vancouver, fur traders had recruited labor from these two gathering sites – a practice that was continued through the early 1850s by the HBC. They included not only Clackamas, Multnomah, Skillute, Cathlamet, Cascades, Chinook proper, and Clatsop Chinookans, but also Kalapuya, Molalla, Klickitat, Yakama, Wasco, Wishram, Umatilla, Tillamook, and many others. These many different peoples who fished and otherwise gathered at these falls were well-represented among the Indian labor at the fort as well as among the wives of its employees.

Working at Fort Vancouver and Throughout the Northwest

As in all matters, the Company’s use of labor from different tribes was strategic, and as time passed the HBC recruited Indian labor from an ever expanding field of tribes from throughout the Northwest. There are innumerable references to Indians, often Chinookan peoples or their Indian slaves, serving as canoemen. Others – Chinook, Cowlitz and others – served as river pilots, as did the Iroquois, Native Hawaiian, and Métis employees of the Company. Travelers also routinely recruited guides and boatmen from the villages sitting most proximate to the fort. The fort’s gardens were overseen especially by the Native Hawaiians and French Canadians, with occasional Klickitat and Iroquois participation. “All the salmon caught in the river [were] caught by the natives” for the HBC commercial salmon operations that sent barrels of preserved fish to Hawaii and other destinations. Indian laborers from numerous tribes worked alongside Hawaiian, Métis, and French-Canadian men in the HBC lumber mill and stock raising enterprises. On the margins of the formal economy of the fort, women from diverse tribal backgrounds sometimes could acquire work independently, sewing for men in the fort and performing other tasks. Other informal economies were to be found; visiting British Army Lieutenants Warre and Vavasour, for example, noted Indians gathering driftwood along the banks of the Columbia and selling the wood or trading it for goods with the residents of the Fort. Indian and Métis labor could be found everywhere in association with the fort’s daily operations: shipping and loading, blacksmithing and horse care, cooking and cleaning. Only perhaps in clerical and administrative functions were the Indians, and to a lesser degree, the Métis, not fully participating members of the fort economy.

Simultaneously, the HBC employed Indian men locally at their forts throughout the Northwestern interior, such as Fort Spokane, Kalispell House, Fort Colville, and Fort Okanagan. In these posts, smaller and more isolated from the principal currents of shipborne trade, security and labor shortages were persistent issues and the recruitment of local tribal members was essential to their success. In the course of their duties, these employees often found their way to Fort Vancouver, either as visitors or as temporary residents, so that Spokane, Pend d’Orielles, Okanogan, Shushwap, and other interior groups were often well-represented at Fort Vancouver.

Simultaneously, the later development of Fort Nisqually, Fort Langley, Fort Victoria, and the Puget Sound Agricultural Company had a similar effect, bringing a diverse assortment of men from Chehalis, interior Cowlitz, Klallam, Nisqually, Snohomish, and other western Washington tribes to the fort as short-term or long-term visitors. Almost every part of the region was represented through these connections to their most proximate forts. Likewise, Fort Vancouver’s British, French-Canadian, Native Hawaiian and Iroquois employees often moved between these forts. These men married into the tribes of these areas and often brought their wives back with them to reside at the fort. The mixture of tribal affiliations was truly remarkable and, despite longstanding traditions of intertribal marriage, probably without precedent in the region.

Men were recruited from these numerous tribes to serve as hunters, trappers, scouts, guards, and general labor throughout the Company’s sphere of influence in the Northwest – especially in the Northwestern interior among such tribes as the Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Cayuse, Umatilla, Okanagan, and Pend d’Orielles. By hiring these men, HBC brigades gained access into prime trapping and trading territories heretofore inaccessible to outside parties. They passed through Fort Vancouver in numerous capacities. Company and missionary correspondence makes reference to Indian couriers who traveled between Fort Vancouver and the many other HBC posts and other settlements throughout the Oregon Territory. Many of these individuals appear to have been recruited from the tribal communities living near HBC outposts, so that – for example – Walla Walla couriers were reported making the trek between Fort Vancouver and Fort Walla Walla. Moreover, numerous Indian interpreters passed through Fort Vancouver, from tribes such as the Spokane and Nez Perce.

This situation was by no means static, but changed dramatically over the course of HBC occupation at Fort Vancouver. Increasingly, Fort Vancouver served as “the peace-keeping and dispute-settling authority for whites and those Indians involved with them…By 1830…the region itself had altered in scope and organization. The post (Ft. George, later Ft. Vancouver), had started to become the central place for an enlarged social region including both whites and Indians” (Hajda 1984: 272-73).

This social region united a growing network of tribal communities from the interior and even outlying places along the coast, all centered on Fort Vancouver. The fort was a place for meetings and negotiations between the various tribal communities, and the principal nexus of exchanges between the Indian and white worlds. Fort Vancouver also had the distinction of being an outpost of European culture and custom – the largest from San Francisco Bay to Sitka – drawing most non-Indian visitors to the region into its halls. For no less than 25 years, the fort would play a central role in almost every aspect of the region’s larger history.