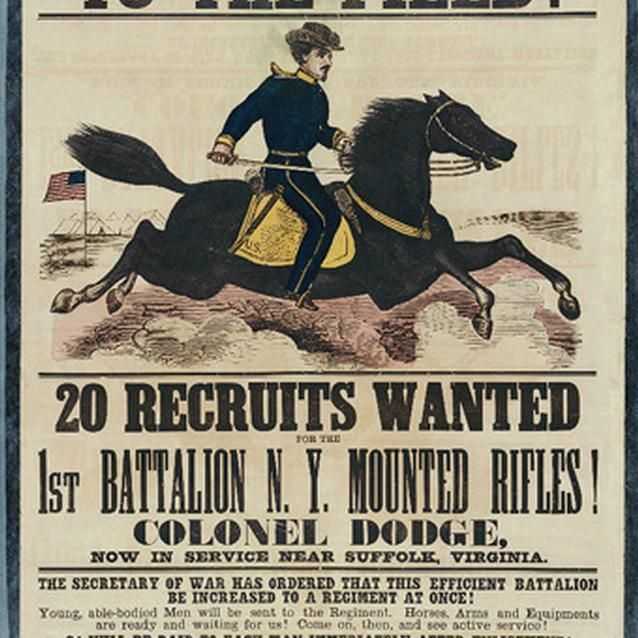

Cavalry acted as the eyes and ears of the army for both the Union and Confederacy, conducting reconnaissance and gathering intelligence. In addition to combat, cavalry also screened marches of infantry, guarded wagon trains, and raided enemy supplies. Troopers and their mounts trained to deploy and perform maneuvers in disciplined coordination. Although cavalry charges occurred, the troops more commonly engaged in combat dismounted. Mounted troops could move quickly while on campaign, but were dependent on the health of their horses, and the availability of fodder and water.

Cavalry

Library of Congress

Early in the war, under commanders such as the audacious Gen. James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart, Confederate cavalry developed a reputation of superior horsemanship. Repeated victory over their Union foes only increased their fame. Punishing raids on the rear of the Union army, destruction of railroads and telegraph lines, and valuable intelligence gleaned from reconnaissance forays by Rebel troopers demonstrated the Confederate cavalry's initial superiority over Union mounted troops. By the Second Battle of Manassas in August 1862, the Union cavalry was improving its skill, confidence, and leadership.

On August 30th, 1862 Confederate Gen. Beverly Robertson's cavalry brigade dashed behind the Union line, expecting to easily sever their route of retreat. Gen. John Buford's Union cavalry brigade engaged Robertson in a swirling mêlée of horseflesh, clanging steel, acrid smoke, and searing lead. Although driven back over Bull Run, Buford's troopers blunted the Confederate attack and preserved the Union avenue of withdrawal. With this critical action, Federal cavalry began to demonstrate the prowess and competence that would define their future success.

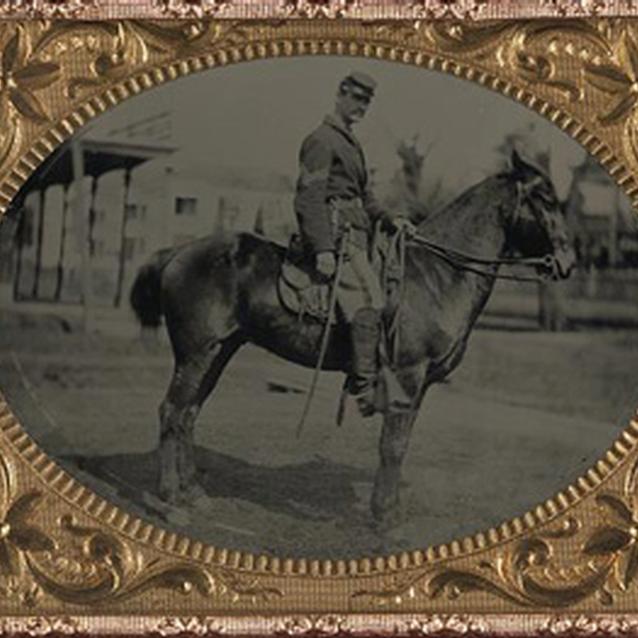

A Horse Named Tartar

Library of Congress

When the Civil War began, Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery traveled by rail to Washington, D.C. from service in Utah. Coming with them was Lt. James Stewart and his horse, Tarter, who had conquered disease and the deserts of the West. Together they served with the artillery at the Second Battle of Manassas.

The bloodshed of the battle began in the twilight of August 28th, 1862. Deploying onto a ridge off the Warrenton Turnpike, Battery B supported the Union advance up the sloping fields at Brawner Farm against the Confederate troops of Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson. For over two hours, until nightfall, troops stood in disciplined lines of battle less than 80 yards apart and unleashed blistering musketry fire upon one another, inflicting horrendous casualties in one of the most concentrated and stubborn infantry encounters of the war. Artillery supported the close lines of foot soldiers, and the guns of the opposing batteries dueled.

During the artillery exchange, Tartar was struck by splinters of a burst shell and wounded in both hips. The horse's tail was also severed by the blast, and his wounds reddened the dirt under his hooves. Stewart believed the horse too seriously maimed to ride further, and released his mount into a fenced farmyard. Tartar, though, was not ready to be put out to pasture. He jumped the fence and followed the battery. The tailless horse quickly recovered and loyally remained with the his unit.

Months later, during the Fredericksburg campaign, the Union Army of the Potomac was reviewed by President Abraham Lincoln. The President's son, nine-year-old Tad, rode along mounted on a pony. Lincoln noticed the tailless Tartar, and called for the officer who rode the horse, as he wished to see the wound. When Stewart rode up to Lincoln, the president declared, "This reminds me of a tale!" and he told a humorous anecdote. Unfortunately, Stewart could not hear the gist of the tale as the generals clustered around Lincoln crowded out the lieutenant on his tailless mount who had given rise to the president's comic story. Tad approached Stewart astride Tartar and launched into some horse trading, insistent that Tartar be given to him. Stewart "had a hard time to get away from the little fellow" but kept his horse.

In the ensuing Battle of Fredericksburg (December 13th, 1862), Tartar, fearless up to this point, was again wounded and became shy of the rattle of musketry. Nevertheless, Stewart rode Tartar in further campaigning, and on the march to Gettysburg, the horse was injured in his fore hoof by a nail and lamed. Tartar was left with a Pennsylvania farmer, but a month later in August 1863, Stewart heard that his tailless horse was tied up in the herd of mounts for Judson Kilpatrick's Cavalry Division. Stewart investigated the story and found Tartar there. He retrieved his horse, and Tartar served as Stewart's mount until the war ended at Appomattox Courthouse. Stewart was promoted to a captaincy in the 18th U.S. Infantry in 1866, and sadly left Tartar with the artillery, after a decade of faithful service from the horse.

Part of a series of articles titled The Burden of Beasts.

Previous: Animals of the Armies

Last updated: February 4, 2015