Last updated: February 22, 2018

Article

Early History

Courtesy of Lorie Garcia, Santa Clara local historian

The physical geography of Santa Clara County, situated between the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west and the Diablo Mountain Range to the east, was formed quite recently in geological history. Santa Clara Valley was created by the sudden growth of the Santa Cruz Mountains and the Diablo Mountain Range, during the later Cenozoic era. This was a period of intense mountain building in California when the folding and thrusting of the earth's crust, combined with active volcanism, gave shape to the present state of California. Hence, Santa Clara Valley is a structural valley, created by mountain building, as opposed to an erosional valley, or one which has undergone the wearing away of the earth's surface by natural agents. The underlying geology of the Santa Cruz Mountains was also formed by the sediment of the ancient seas, where marine shale points to Miocene origin. Today one can still find evidence of this in the Santa Cruz Mountains, where shark's teeth and the remains of maritime life are still found as high as Scott's Valley, a city nestled in the mountains.

The Santa Cruz Mountains and Diablo Mountain Range created a sheltered valley. Located south of the San Francisco Bay, Santa Clara Valley offered shelter from the cold, damp climate of the San Francisco region and coastal areas west of the Santa Cruz Mountains, and was no doubt inviting to the first human inhabitants. Historically, the Tamien-speaking Ohlone Indians were the first documented inhabitants of the Santa Clara Valley region, although the oak lined hills and valley undoubtedly had known earlier Indian inhabitants and migrations, now lost to history and prehistory. Archeological discoveries place Ohlone Indian settlements in the region as early as 8000 BC.

Courtesy of Lorie Garcia, Santa Clara local historian

Sometime around 4000 years ago, according to anthropologists, the ancestral Ohlone, along with the culturally interrelated people of the greater Sacramento/ San Joaquim Delta regions, developed a system of social ranking and institutional religions. Within the greater San Francisco Bay region, people of social prominence were interred in what has become known as the "shellmounds." Some of the last elders in the Ohlone region to speak their native languages were interviewed by Smithsonian linguist J.P. Harrington who worked in the area from 1921 to 1939. In their conversations with Harrington, Angela Colos and Jose Guzman, Muwkema elders of the Federally Recognized Verona Band of Alameda County, shared that "the Clareños [Santa Clara Valley Ohlones] were much intermarried with the Chocheños [East Bay speaking Ohlones]. Aside from the Ohlone, who are also considered Costanoan speaking tribal groups, the Bay Miwok and Yokut peoples dwelt to the east in parts of modern Contra Costa and San Joaquin counties. The northern San Francisco Bay was home to both the Coast Miwok and Patwin speaking tribal groups, and other tribes who lived in the surrounding regions. Descendants of Santa Clara's original Ohlone inhabitants are still in the region today and are enrolled members of the present-day Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay.

The European presence in the region began with the English explorer and privateer Sir Francis Drake, who landed on July 17,1579, in the San Francisco Bay Area and claimed the region for England. After Drake's departure it took nearly two centuries before any European power settled the region. The arrival of the Spanish to "Llano de los Robles"-Plain of the Oaks-started when Russian exploration into California alarmed the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico City. The Russians had settled Alaska and were exploring the West Coast for trading posts within striking distance of the rich Spanish mines. They were a presence at Fort Ross in Northern California from 1812-1841. José de Gálvez, the visitor-general of New Spain (Mexico), wanted to increase New Spain's territory for the Spanish crown. He sent the Spanish forward into Alta California (present day California). Encountering the native Ohlone people, the Spanish gave them the name of Costeños, or People of the Coast. José Francisco Ortega gave Santa Clara the name "Llano de los Robles" in 1769 as he scouted the region on the behalf of Captain Gaspar de Portola. On April 2, 1776, near the Carquinez Straits (North-East Bay), Father Font documented the following account of an early encounter between the Spanish and the Ohlone:

Photograph by Judith Silva, courtesy of the City of Santa Clara

We set out from the little arroyo at seven o'clock in the morning, and passed through a village to which we were invited by some ten Indians, who came to the camp very early in the morning singing. We were welcomed by the Indians of the village, whom I estimated at some four hundred persons, with singular demonstrations of joy,singing, and dancing.

Father Junípero Serra also came into present-day California, establishing a chain of Franciscan missions. It was in 1777 that Father Serra gave Santa Clara Valley its lasting name when he consecrated the Mission Santa Clara de Asis. The 8th of the 21 established missions, Mission Santa Clara de Asis claimed land from San Francisquito Creek in present day Palo Alto to Llagas Creek at Gilroy.

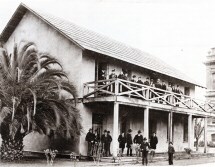

San Jose was California's first town. On November 29, 1777, on orders from the Spanish viceroy of Mexico, nine soldiers, five pobladores (settlers) with their families, and one cowboy were detailed to found the Pueblo de San Jose de Guadalupe, named in honor of St. Joseph. The already existing Spanish Catholic missions were not pleased with this, but could do nothing to stop it. By 1825, Mission Santa Clara de Asis, standing where the University of Santa Clara stands today, offered rest for the travelers from Monterey and San Francisco. Phyllis Filiberti Butler, in The Valley of Santa Clara Historic Buildings, 1792-1920, states "The padron of 1825 showed 1,450 devout souls at Santa Clara, most of whom were Indian neophytes." Although Mexico broke with the Spanish crown in 1821, it was not until May 10, 1825, that San Jose acknowledged Mexican rule. The Mexican government soon began selling off church lands in a process known as "secularization." Although originally intended to return church lands to the native population, this practice soon entailed a selling of church lands to the highest bidders. By 1839 only 300 Indians remained at the Mission Santa Clara de Asis. The time of the Mexican dons, comprised of the rural land owning gentlemen, was short lived in California, however. American immigrants began arriving in California, followed by the Mexican-American War.

Photograph by Robert W. Kerrigan, courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey or Historic American Engineering Record, Reproduction Number HABS, CAL,43-ALMA,8-1

On May 13, 1846, the United States declared war on Mexico. Captain Thomas Fallon, leading 19 men, entered San Jose on July 14, 1846, and raised the United States flag over the town hall. San Jose consisted of a small town of Spanish Californians, Mexicans, Peruvians, Chileans, and Indians. After the completion of the Mexican-American war, in 1848, California, along with most of the western states, was added to the United States, first as a territory, but later as a state on September 9, 1850. In addition to the change of government, the discovery of gold in 1848 in a gravel bed of the American River altered Santa Clara's political landscape. Suddenly swarms of immigrants arrived in California, looking to strike quick fortunes. The Gold Rush changed San Jose, which became a supply city for the numerous miners arriving in California. Many residents, alarmed by the arrival of so many Americans into the valley, fled to Mission Santa Clara. The Catholic bishop of California took an interest in the location, and by 1851 the Jesuits had set up the first college in the new State--Santa Clara University, on the rebuilt site of the old mission.

San Jose became the first Capital of the State of California and the first California Legislature convened there on December 15, 1849. A referendum was sent to the people, to determine where to permanently locate the Capital. Vallejo, San Jose and Monterey vied for the honor, and Vallejo initially won. After several more moves the capital was permanently established in Sacramento. The name Santa Clara was given to the county by the new state legislature in 1850. Other towns began to spring up in Santa Clara County after the gold rush. In 1852 Santa Clara became a town with duly elected trustees. The city of Mountain View is reported to have received its name when Jacob Shumway, a storekeeper, looked across the valley eastward and poetically named the place where he was standing "Mountain View." In September of 1855 a small town, originally named McCarthysville, but later named Saratoga, came into existence 12 miles west of San Jose at the base of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Saratoga became famous for its wine and spa, while Cupertino, which possessed a post office by 1882 and named after the original Spanish name for Steven's Creek, Arroyo de San Josè Cupertino, was famous for horse breeding. Los Gatos was formed from land originally owned by the British vice-consul to Mexican California, James Alexander Forbes. When Forbes went bankrupt, many pioneer lumbermen came down to the banks of Los Gatos creek and established the nucleus of the town. Gilroy, in the southern part of the county, was named after British settler John Gilroy, who wed Maria Clara, granddaughter of the man who claimed San Francisco for Spain in 1769.

Photograph courtesy of the National Register of Historic Places collection

In 1849 Martin Murphy, Jr. controlled six of Santa Clara's largest ranchos. After Murphy's death real estate developer W.E. Crossman purchased 200 acres of orchard land, which eventually became Sunnyvale in 1901. Palo Alto's original townsite was laid out in 1888 from land owned by Rafael Soto. It was here in the 1890s that California Senator Leland Stanford established the Leland Stanford Junior University in Palo Alto. The railroads soon followed the establishment of Palo Alto and the university. Paul Shoup, a Southern Pacific executive, spotted a good site for a township and organized the Altos Land Company. By 1908, the railroad began service and Los Altos filled up with buyers.

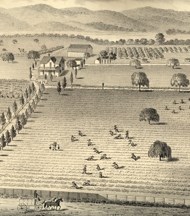

Santa Clara County was linked to the world by the railroads, and despite a rapid population growth since 1850, the county retained her natural beauty. Agricultural success in the Santa Clara Valley was fostered by access to distant markets that the railroad made possible. This, combined with the discovery that artesian well water underlay the whole valley, created the conditions for the sudden wealth to be found in the agricultural business. Santa Clara County was soon producing carrots, almonds, tomatoes, prunes, apricots, plums, walnuts, cherries, and pears for the world market. With the establishment of seed farms in the last half of the 1870s, a new aspect of the agricultural business began. The Charles Copeland Morse Residence is an example of the wealth to be found in the seed business. Santa Clara Valley was also experimenting with other sources of income. Oil wells once dotted the valley, and from 1866 until the discovery of other sources in 1880, the county produced nearly all of California's oil. Lumber also played a part in the county's economy; the town of Santa Clara saw the Pacific Manufacturing Company producing such items as Cyclone windmills and coffins. This company eventually became the largest manufacturer of wood products on the West Coast. Several wineries, such as the Picchetti Brothers Winery and the Paul Masson Mountain Winery were operating, and the area southwest of Cupertino was a winemaking region for years. Santa Clara County, with its farms, orchards and ranches remained largely rural and agricultural until after World War II. John Muir, the renown conservationist, testified to the rural beauty of the county, writing in 1868: "It was bloom time of the year . . .The landscapes of the Santa Clara Valley were fairly drenched with sunshine, all the air was quivering with the songs of meadowlarks, and the hills were so covered with flowers that they seemed to be painted."

Thompson & West Historical Atlas, 1876

Courtesy of City of Santa Clara

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which struck at 5:16 AM on the morning of April 18, shook San Francisco to its foundations, destroying its business district and taking over 700 lives. Nearby Santa Clara County also received reverberations from the quake, which was felt as far away as Los Angeles, Oregon, and Nevada. It is also said locally that the Landrum House was one of the few buildings in Santa Clara whose chimney did not crumble in the earthquake of 1906. The Paul Masson's Mountain Winery was rebuilt after the earthquake, using sandstone blocks from the Saratoga Wine Company's building on Big Basin Way, also destroyed in the great quake. While Santa Clara County recovered from the quake, the later changes that the new century ushered in would have a much more dramatic effect on the valley and the world.

Much of the information for this essay was found in Phyllis Filiberti Butler's, The Valley of Santa Clara Historic Buildings, 1792-1920 (with architectural supplement by the Junior League of San Jose). Menlo Park, California: Bay Research Press, 2002. Also helpful was the Federal Writers' Project book, California: A Guide to the Golden State. New York: Hastings House, 1939. For an overall view of Spanish/Mexican history in the west, Howard R. Lamar's (editor) The New Encyclopedia of the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998 was helpful. On local Santa Clara history, the book draft of Lorie Garcia's manuscript for The City of Santa Clara Sequicentennial Book was helpful. Information on the Ohlone Indians was found at The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area in a history essay by Rosemary Cambra (Tribal Chair), Monica V. Arellano (Tribal Vice Chairwoman), Hank Alvarez (Tribal Councilman), Gloria E. Arellano (Tribal Councilwoman), Carolyn M. Sullivan (Tribal Councilwoman), Karl Thompson (Tribal Councilman), Concha Rodriguez (Tribal Councilwoman), and Alan Leventhal (Tribal Ethnohistorian). This was found at http://www.muwekma.org/