"(Blacks have) for more than a century...been regarded as beings of an inferior order... and so far unfit that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." U.S. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in Scott v. Sanford, 1857

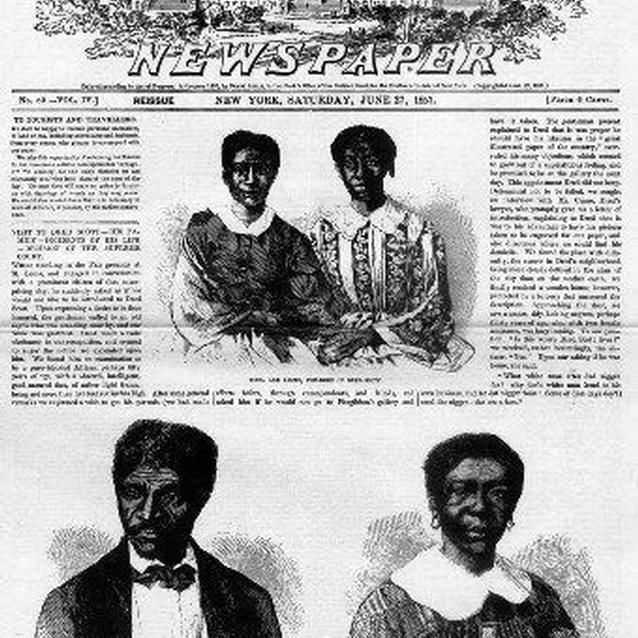

Library of Congress

The Dred Scott case was first brought to trial in 1847 in the first floor, west wing courtroom of St. Louis' Old Courthouse. The Scotts lost their first trial because of hearsay evidence, but were granted a second in 1850. In the second trial, a jury heard the evidence and decided that Dred Scott and his family should be free.Slaves were valuable property, and Mrs. Emerson did not want to lose the Scotts, so she appealed her case to the Missouri State Supreme Court, which in 1852 reversed the ruling made at the Old Courthouse, stating that "times now are not as they were when the previous decisions on this subject were made." The slavery issue was becoming more divisive nationwide, and provided the court with political reasons to return Dred Scott to slavery. The court was saying that Missouri law allowed slavery, and it would uphold the rights of slave-owners in the state at all costs.

Dred Scott was not ready to give up in his fight for freedom for himself and his family, however. With the help of a new team of lawyers who opposed slavery, Dred Scott filed suit in St. Louis federal court in 1854 against John F.A. Sanford, Mrs. Emerson's brother and executor of the Emerson estate. Since Sanford resided in New York, the case was taken to the federal courts due to diversity of residence. The suit was heard not in the Old Courthouse but in the Papin Building, near the area where the north leg of the Gateway Arch stands today. The case was decided in favor of Sanford, but Dred Scott appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the majority opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case. Seven of the nine justices agreed that Dred Scott should remain a slave, but Taney did not stop there. He also ruled that as a slave, Dred Scott was not a citizen of the United States, and therefore had no right to bring suit in the federal courts on any matter. In addition, he declared that Scott had never been free, due to the fact that slaves were personal property; thus the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was unconstitutional, and the federal government had no right to prohibit slavery in the new territories. The court appeared to be sanctioning slavery under the terms of the Constitution itself, and saying that slavery could not be outlawed or restricted within the United States.

Last updated: April 6, 2016