NPS Photo

The bus driver broke the silence, announcing by microphone, “There’s a wolf ahead, and it’s coming this way.” As shuttle bus passengers reached for their cameras, she began to whisper, “There’s a second wolf too. Get your windows down, and stay quiet.”

The first wolf was gray with a few reddish streaks at his muzzle and ears. He trotted with lanky, effortless strides, fur slightly furrowed with the drizzle. He hesitated only briefly before passing alongside the bus, eyes forward, ignoring the open windows, clicking cameras, and the wide-eyed, awestruck viewers. His large GPS (global positioning system) collar indicated he was the alpha male—previously captured and collared to track his movements. The second wolf was red on the face and legs, and a bit more wary—she turned to look at the bus with piercing yellow eyes. In a few moments, both wolves were gone, but the spell of silently watching wild wolves—their gait, their fur, their yellow eyes— lingered for the rest of the bus trip.

Special wolf viewing opportunities such as this may decrease in the future.

Protecting wolf viewing opportunities

Each year, 20,000 to 30,000 visitors to Denali National Park and Preserve view wolves along the park road—on the tundra, a gravel bar, or the road itself. Denali is recognized as one of the best places in the world for people to see wolves in the wild. Wolf viewing offers park visitors and the Alaska tourism industry substantial benefits.

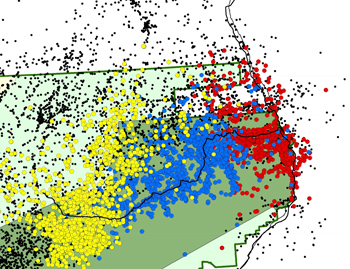

Wolf viewing opportunities are provided primarily by three packs of wolves that live near the park road (see Map 1). These viewing opportunities in Denali depend mainly on the behavior of individual wolves that frequent the park road. While the degree of tolerance to humans may vary widely among wolves, it is likely that the wolves that are most tolerant of humans, and therefore most often seen by humans along the park road, are the same ones that are most vulnerable to being legally harvested (i.e., trapped and shot) when they venture fearlessly beyond park boundaries.

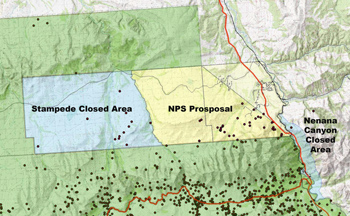

In 2000, certain areas adjacent to the park boundary were closed to the taking of wolves, in order to protect wolf viewing opportunities in the park. The size of the closed areas changed several times, but from 2004 to 2010, these closed areas totaled 316 km2 (122 square miles) (see blue areas on Map 3). These closed areas are located in Alaska Game Management Units (GMU) 20A and 20C.

Analysis of data from GPS radio collars placed on wolves by park wildlife biologists showed that from 2003 to 2009, two of the three most commonly viewed wolf packs in the park occasionally traveled east of the Stampede Closed Area into areas where they were vulnerable to harvest.

Effects of wolf harvest near the park

The taking or harvest of wolves (particularly breeding wolves) near the closed area in what are known as the Wolf Townships or the Stampede Corridor, has the potential to (1) decrease wolf numbers in the park, (2) alter wolf behavior, (3) decrease opportunities for wolf viewing by park visitors, and (4) increase the likelihood of sightings of wolves with trap-related injuries.

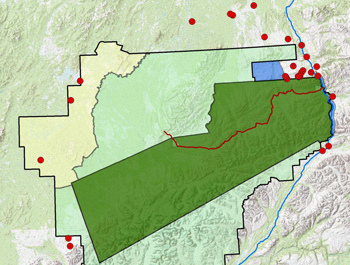

In 2009, wolf numbers in the park were lower than any time in more than 20 years. The spring 2010 estimates of population size in the park were even lower. Using wolf tracking data in Denali to compare the locations where radio-collared wolves were killed by humans in recent years (2003-2009) compared to such locations in the early years (1986- 1994), park biologists have demonstrated that wolf harvest has concentrated increasingly on areas just northeast of the park (see Map 2). Lowered population size of wolves in Denali has little effect on wolf populations at a regional scale, but can have significant, year-long effects at the park level, and thus can have substantial impacts on visitor experiences.

Another consequence of wolf trapping just outside the park is the increase in sightings of wolves bearing trap hardware and injuries. In the winter of 2007- 2008, many people saw one wolf with a gaping throat wound from a broken snare still around his neck. A second wolf with a snare was also seen in the park, as was another wolf with a trap clamped to its foot. Such sightings have a detrimental effect on public opinion of trapping and wildlife management.

NPS proposal to extend closed areas

The NPS supports maintaining the Stampede and Nenana Canyon Closed Areas (see blue areas on Maps 2 and 3), which the NPS believes have protected both the wolves that live near the park road and the wolf viewing opportunities for park visitors.

Park managers have evaluated the effects of several options for the Stampede Closed Area. Based on the documented locations of wolves from the three “park road packs” beyond the park boundary (dots on map based on collared wolf data), the expanded closed area would provide almost complete protection of the wolves from the Teklanika-Toklat area of the park (yellow and blue packs, Map 1) and 75 percent protection for the wolves at the east end of the park (red dots, Map 1) when they leave the park. That is, of the colored dots beyond park boundaries, none of the yellow and blue dots, and only one fourth of the red ones, was located outside the closed areas as proposed by NPS.

At a 2010 meeting of the Alaska Board of Game, the NPS proposed a closed area extension that would enlarge the closed area by 64 percent by adding the yellow area (Map 3). Instead, the Board of Game decided to eliminate both closed areas and allow hunting and trapping wolves in all areas bordering the park. View data on wolf sightings in the park since 2010.

Last updated: January 28, 2016