NPS Photo / Ken Conger

During the spring of 1985, Denali employees found the skinned carcasses of seven wolves in remote parts of the park. The resource manager at the time, John Dalle-Molle, was concerned that little was known about the park’s wolves. He decided that a radio-collaring study of wolves would reveal how widespread such aerial poaching was, what caused most wolf mortality, and how commonly wolves traveled beyond park boundaries.

Researchers L. David Mech and Layne Adams (both now with the U. S. Geological Survey) initiated a wolf collaring project in early 1986. For the last 25 years, the effort has continued, with field work headed up at various times by Layne Adams, Tom Meier, John Burch, Steve Arthur, and Bridget Borg.

More than 400 wolves have been captured and collared. Collared wolves are monitored from antenna-equipped Supercub aircraft about twice per month. In recent years, wolf locations have also been monitored with GPS/ARGOS collars, which determine a wolf’s location at least once each day and upload the data through the ARGOS satellite system.

Wolf Numbers

Denali’s wolf population shows natural fluctuations in abundance due to changes in mortality, number of pups born, and the number of wolves moving in and out of the population. Prey density, vulnerability, and environmental conditions also play important roles in driving these changes.

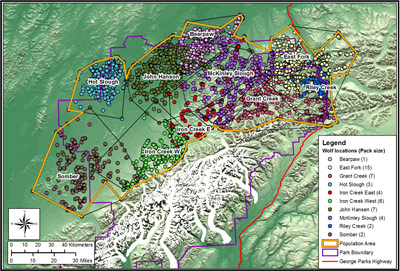

Each year in early spring, biologists produce a map of wolf pack territories from the telemetry data, and estimate the density and numbers of wolves in the park. At the start of the study in 1986, wolf density in the park was very low. A series of mild winters had made it difficult for wolf packs to obtain food in winter, and poaching may also have lowered wolf numbers. A series of deep snow winters benefited the wolf population, and numbers increased rapidly as many wolves were born and survived, and few left their packs. One pack, the East Fork Pack, increased from 6 to 29 wolves in three years. Since then, the density of wolves in the park has fluctuated between 2.9 and 9.8 wolves per 1000 square kilometers (7.4 to 25.4 per 1000 square miles), a low density when compared to more temperate climates with more abundant food.

NPS Photo / Ken Conger

Wolf Food Habits

Following collared wolves has provided an opportunity to learn a great deal about wolf diets. When biologists locate wolves, they often find them interacting with prey animals or feeding on kills.

Researchers visited more than 850 kill sites between 1986 and 1993 to learn what prey animals wolves were selecting. Among the results: Wolves kill many very young animals (moose and caribou calves, Dall’s sheep lambs), many older animals, but few young adults of the three major prey species. In winters without much snow, wolves feed mainly on moose, which make up the largest share of food available in the park. In winters with deep snow, wolves kill more caribou. Some wolf packs learn locations and techniques for killing Dall’s sheep and obtain a large portion of their diet from them.

Wolves in Denali, like wolves everywhere, rely mostly on ungulates (hoofed animals) for their food, but also have other important food sources, including beavers in summer, snowshoe hares when they are plentiful, and, most surprisingly, salmon.

Three species of salmon (chum, silver, and king) are known to spawn in the northwestern part of the park after having traveled more than 1,000 miles from the ocean. Dr. Adams has calculated that the biomass of chum salmon equals the biomass of ungulates (moose and caribou) in that area.

Areas of upwelling, where rivers remain open in the winter, provide predictable sources of dead salmon for a wide variety of birds and mammals, including wolves. Some of the concentrations of wolf locations in remote parts of the park are at such areas. Salmon carcasses may be a food of last resort for hungry wolves. It is common to find packs and individual wolves traveling long distances to get to salmon springs and to find wolves being killed by other wolves as packs interact there.

Mortality of Collared Wolves

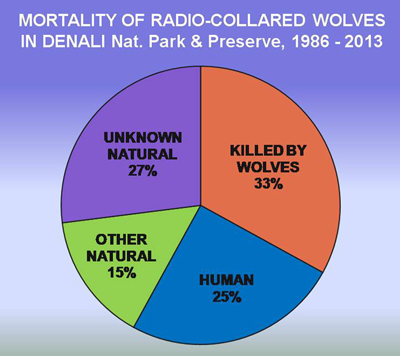

From 1986-2013, of 238 collared wolves that died, about 25 percent were killed by humans, mostly through legal harvest when they ventured outside park boundaries. (In other areas of Alaska where wolves are not protected, and in some areas where wolves are actively controlled, humans kill up to 64% of the wolf population annually.) At least one-third of the 238 collared wolves were killed by neighboring wolf packs, generally in winter when packs roam beyond their usual territories. The remainder (about 42 percent) died of other unknown natural causes. Many of these remaining wolves were too decomposed or consumed to determine the cause of death, but, undoubtedly, some of these also were killed by wolves. Other known causes of natural mortality include avalanche, starvation, drowning, old age, and disease.

Wolf Management

Wolf monitoring has had many benefits for park management, including achieving the original goal of assessing the causes of wolf mortality and the degree to which park wolves travel outside the park boundary. Another benefit has been knowledge of where active wolf dens and rendezvous sites are, so that closures can be created to protect wolf pups from human interference.

Wolf numbers and distribution have been identified as a vital sign for long-term monitoring by the Central Alaska Network Monitoring Program. The wolf management goals are to maintain natural and healthy wolf populations, where predator/prey systems are intact, and to maintain opportunities for visitors to view wolves in their natural habitat.

Last updated: March 14, 2017