Because they are diverse, abundant, easy to sample, and tightly linked to their host plants, bees may serve as ideal indicators to measure the effects of a changing climate on critical ecosystem services such as pollination.

Jessica Rykken

Alongside the path to the Visitor Center during July 2012, there was an intriguing and colorful array of short plastic cups—blue, yellow, and white—spaced about 5 meters (5 yards) apart. Although at first the cups may have looked like odd and regularly-spaced trash, the cups had been thoughtfully painted to take on the appearance of flowers. The idea was to have insect pollinators be lured to investigate the “flowers,” fall into the cups, and be trapped in the soapy water. The cups are called bee bowls and were part of Denali National Park and Preserve’s first survey of insect pollinators.

What Insect Pollinators are in Denali?

Pollinators are the specialty of Dr. Jessica Rykken, entomologist from the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University. She was selected as Denali’s Researcher-in-Residence in 2012 and spent six weeks in the park in June and July conducting her preliminary survey of pollinators.

Even though many insects, including butterflies, beetles, bees, and a variety of flies, pollinate plants in Denali, during her residency, Rykken focused on bees (Anthophila) and flower flies (Family Syrphidae). She sampled in a wide variety of habitats that she could access easily along the road corridor (see map). Her primary objectives were (1) to document the diversity and distribution of these two important pollinator groups and (2) to record general habitat associations for each species.

Bee Bowls, Vane Traps, and a Net

Almost all species of bees and flower flies can be identified only with the help of a microscope, so just observing pollinators is not sufficient to make a checklist of species. By collecting the pollinators, and creating voucher specimens, she could identify the bees and flower flies and also document her findings.

In addition to using the bee bowls (in sets of 30 cups) set out during the warmest part of the day, Rykken also used blue vane traps and a butterfly net. The vane traps work by attracting pollinators to the colorful vane mounted above a funnel and jar on a stake. Once an insect flies into the jar through the funnel, it cannot find the exit—trapped! In addition to the passive sampling using bee bowls and vane traps, Rykken actively swung a net to sample bees and flies while they were flying or feeding at flowers.

Between mid-June and late July, Rykken and her assistants (staff, visitors, and volunteers) sampled pollinators in dozens of locations, choosing sites where plants were flowering. Rykken trapped and netted pollinators in several habitats including alpine meadows and rocky areas, stream edges and gravel bars, and trail- and roadsides. At each site, she recorded the dominant plants in bloom.

Rykken completed the identification of bees herself and sent the flower flies to expert Dr. Chris Thompson at the Smithsonian Institution.

Jessica Rykken

Findings: A Diversity of Pollinators

Even though the summer of 2012 was unusually cool and wet, Rykken collected 552 bees and 328 flower flies from about 60 sites. The majority of bees were collected by net, while more than half of the flower flies were collected in bee bowls. Vane traps were largely unsuccessful. Thirteen species of bumble bees accounted for 91 percent of the bee catch—there are 20 bumble bee species known in Alaska—with three species represented by more than 100 specimens: Bombus frigidus, B. mixtus, and B. sylvicola (see portraits below). The other seven bee species were solitary bees and one cuckoo bee (80 species total known in Alaska). In comparison, there were more than twice as many species of flower flies than bees (42 versus 20 species), including several species that are likely to represent new discoveries for Alaska (190 species previously known).

Among all the pollinators, many species were generalists, occurring in several habitats across a wide range of elevations. A few species were associated with higher or lower elevations, e.g., all solitary and cuckoo bees were collected at lower elevations near the park entrance.

There were two noteworthy finds:

(1) a species of flower fly new to science in the genus Cheilosia. Cheilosia is a diverse genus in which many larvae feed on live plants or fungi. So far, the biology of Denali’s new species is unknown.

(2) a bumblebee of special concern, Bombus occidentalis (Western Bumblebee). This western species has suffered drastic population declines in the southern portion of its range since the late 1990s. Sites in Alaska may be an important refuge.

The Value of Denali’s Pollinators

Denali’s diversity of bees and flower flies provides critical pollination services to plants and thereby maintains healthy plant communities and functioning ecosystems.

Worldwide, native pollinators are vulnerable to threats such as pesticides, habitat loss, and climate change. For most pollinating insects, too little is known about natural populations to accurately assess their responses to these threats. Even though colorful bee bowls are low-tech, knowing what fell into those bee bowls in Denali has far-reaching implications. Efforts to document the diversity and distribution of native pollinators in a large intact wilderness park will provide reference data on subarctic insect populations—which may be especially vulnerable to effects from climate change.

Jessica Rykken

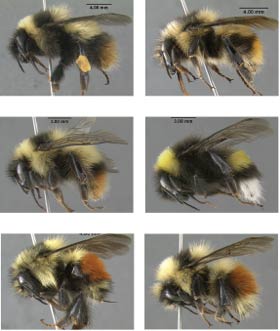

Bumble Bees

Bumble bees (social insects with annual nests; the queens overwinter underground) were the most commonly-collected bees. They are well-adapted to colder climates because of their large body size, thick “fur,” and ability to shiver their flight muscles to regulate body heat. These bees, not mosquitoes, are the primary pollinators of blueberry plants.

In the image at right, starting from upper left and proceeding clockwise, the bees are:

- Bombus balteatus

- Bombus mixtus

- Bombus moderatus

- Bombus sylvicola

- Bombus melanopygus

- Bombus frigidus

Jessica Rykken

Solitary and Cuckoo Bees

Solitary bees, as the name implies, have no castes, each female making her own nest in soil (e.g., mining bees, sweat bees), pithy shrub stems (e.g., masked bees), or holes in wood (e.g., mason and leafcutter bees). Cuckoo bee females lay their eggs in the nests of solitary bees. World-wide, solitary bees are the most diverse bee group.

At right, the two bees shown are Colletes impunctatus lacustris (left) and Hylaeus annulatus (right)

Jessica Rykken

Flower Flies

Most flower flies mimic bees and wasps (black and yellow coloring and body forms), fooling predators into thinking they can sting. Compared to bees, they have relatively large eyes and can hover and fly in all directions. The adults feed on pollen and nectar, and the larvae feed on dung, decaying or living plants, rotting wood, fungi, or aphids.

At right, the two flies shown are Cheilosia bigelowi (left) and Voucella bombylans (right)

Part of a series of articles titled Denali Fact Sheets: Biology.

Previous: Population Biology of the Wood Frog

Last updated: April 21, 2016