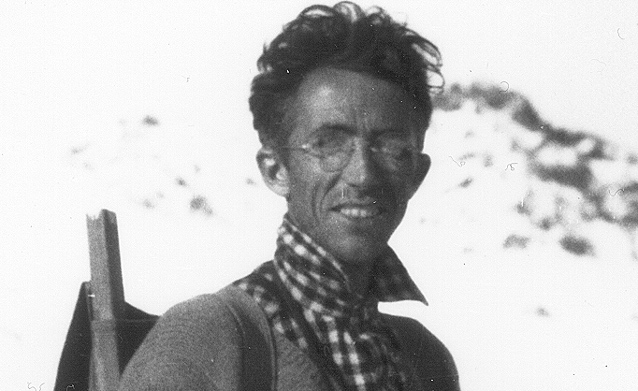

DENA #22782, DNP&P Museum Collection

Adolph Murie has been called “Denali’s Wilderness Conscience.” His life’s work has profoundly shaped wildlife management policies and wilderness conservation in Denali National Park and Preserve (originally named Mount McKinley National Park).

Born in 1899 in Moorhead, Minnesota, Adolph first came to Alaska in 1922 to assist his older half-brother Olaus with a caribou study in the Brooks Range. In 1922 and 1923, the brothers attempted to capture caribou bulls in Mt. McKinley National Park as part of a project to enhance domestic reindeer by breeding them with the larger caribou. Adolph graduated from Concordia College in 1925 with a degree in biology, and the following three summers worked as a seasonal ranger in Glacier National Park. After completing his dissertation on the ecological relationships of deer mouse subspecies, he received a Ph. D. from the University of Michigan in 1929.

In 1932 Adolph married Louise Gillette. Adolph’s half-brother Olaus married Louise’s half-sister Margaret “Mardy” Thomas. Both couples focused their work on wildlife ecology and wilderness conservation.

Adolph was hired in 1934 as a wildlife biologist for the National Park Service (NPS). He studied a variety of species in several park units, including a study of coyote ecology in Yellowstone National Park in 1937.

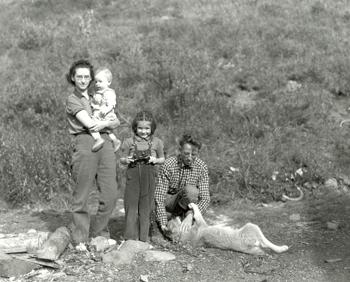

DENA #4-38 (#21267), DNP&P Museum Collection

The Wolf-Sheep Controversy

In the 1920s and 30s wildlife management policy within the NPS was evolving from a predator-control stance to a philosophy of preservation of intact ecosystems, an idea contrary to widely held beliefs. At McKinley Park the Dall sheep population experienced a significant decline in the early 1930s and wolf predation was blamed as the cause. In need of adequate information to support wildlife management decisions, the NPS assigned Adolph Murie to study the wolf-sheep relationship. Adolph arrived at McKinley Park in April 1939 and conducted in-depth field studies through October. He returned in April 1940 and for the next 15 months he focused not only on the wolves and sheep, but the greater ecosystem of interrelated species.

Adolph concluded from his two-year study that the sheep population decline was caused by severe late-winter weather and not wolf predation, and that predators played an important role in an intact ecosystem. This information enabled park managers to eliminate predator control in McKinley Park. He published the results of his study as a government bulletin, The Wolves of Mount McKinley, in 1944. A classic ecological study, the book presented the first in-depth study of wolves and their interrelations with other species.

Harpers Ferry Center, #10565, NPS

Field Biologist

Adolph utilized basic field techniques in McKinley Park. He hiked throughout the park, spent hours observing wildlife behavior, and kept detailed field journals. He collected and analyzed scat to identify food sources, and collected skulls and bones to determine age, sex and health. He photographed wildlife, tracks and habitat.

Beginning the summer of 1940, Adolph brought his family with him to the park. They lived at cabins along the park road during summers and at park headquarters in winter until fall 1941. Adolph served as year-round park biologist from 1947 to late 1950. Along with other NPS assignments, he continued to monitor wildlife populations at McKinley Park through the 1950s. With a winter home for his family in Oregon, he served as the park’s biologist from 1959 until his retirement in January 1965. Adolph and Louise spent six more summers at the park.

Adolph’s wife Louise described his work in the park:

"Ade [as he was known to his friends] spent many hours with telescope and binoculars watching the interactions of the various species of wildlife. It was his habit, after the evening meal, to write in his journal details of each day in considerable detail. But at the same time he was interacting with the people who visited the park, for he met and talked with many of the visitors from all parts of the world, and discussed with them the values inherent in parks. He was always a champion of the national park idea, and expressed the thought that the lands therein should be preserved in their natural condition."

DENA 28-78, DNP&P Museum Collection

Conservationist and Wilderness Advocate

To inform and promote appreciation of wildlife and wilderness, Adolph wrote articles for popular conservation magazines and authored books about McKinley’s mammals and birds. His wildlife movies were made into an interpretive film that he presented for park visitors. He recognized the importance of habitat preservation to support intact ecosystems and believed that erosion of wilderness negatively affected natural systems. He consulted on planning studies, advocated for park boundary extensions, and favored restricted human developments in the park.

Adolph opposed many of the 1950s development projects proposed for the park. He advocated for the preservation of habitat and wilderness spirit and opposed a Savage River hotel development, constructed trails, and roadside signs, considering them to be “unnecessary intrusions.” His opposition to the road improvement plans marked a major transition in the park’s history, elevating the park’s wilderness character as a major value. The park road today reflects his advocacy.

Charles Ott Photo, Denali National Park and Preserve Museum Collection

Murie Legacy

As a scientist Adolph Murie crafted an ecological approach to wildlife management for the park, as a wilderness advocate he fashioned a defining wilderness philosophy, and as an author he effectively shared his observations and philosophy. He was awarded the Department of the Interior’s highest honor, the Distinguished Service Award, in 1965. He died on August 16, 1974.

The Murie Science and Learning Center, a collaborative entity between the National Park Service and its scientific and educational partners, strives to promote, support and communicate scientific research in Alaska’s national parks. The Center bears the Murie name as an acknowledgment of Adolph’s work and the contributions of other members of the Murie family, who served as passionate advocates for the biological integrity of our national parklands.