Part of a series of articles titled Denali History Nuggets.

Article

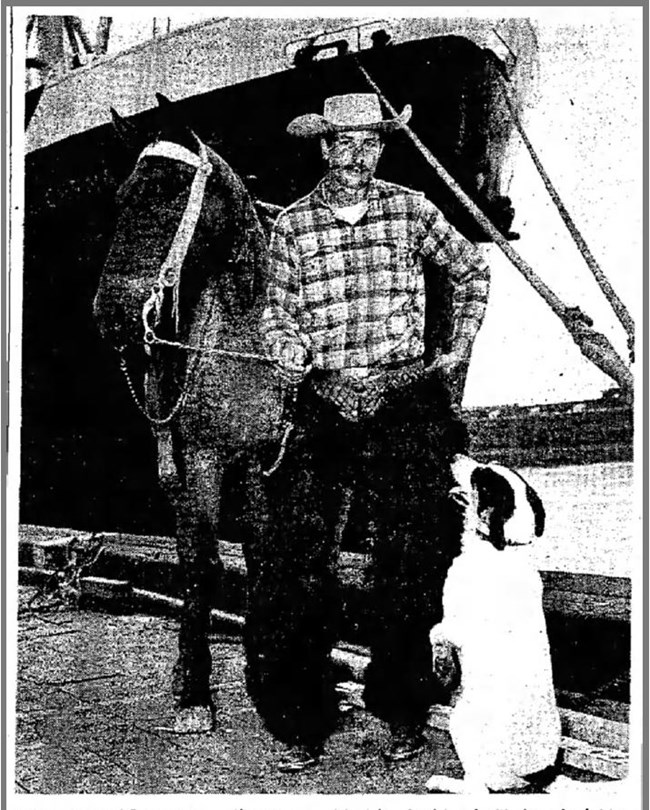

Started from the Bottom: A Mission from Death Valley to Denali on Horseback

By Erik Johnson, Denali Historian

Fairbanks Daily News Miner

The 30-year-old Upton departed Death Valley on New Year’s Day in 1958 and journeyed north with three other men and eight horses. He hoped to travel 25 miles per day and be at his destination by August.

Media from around the country picked up the story. When Park Superintendent Duane Jacobs learned about Upton’s trip in early 1958, he simply stated, “We are of the opinion that this gentleman will alter his plans before reaching his alleged goal.”

Bah humbug, Supt. Jacobs.

The Superintendent’s Report from July of 1959 reported that Upton arrived in the Park on July 30th and terminated his trip at the Eielson Visitor Center.[1] He was a year late and many thousand feet short of his ultimate goal, but he had some stories.

In an interview following his trip, Upton claimed he was glad he went on the adventure but “wouldn’t do it again.” Within a month of leaving Death Valley, Upton’s three companions abandoned the trip. After 500 miles of traveling, his last pack animal quit, leaving him alone with his strawberry roan, Skeeter, to continue. There was a harrowing 700-mile stretch of Canada where he nearly starved to death, dropping 43 pounds and subsisting on horse oats. During this stretch he almost drowned in the Stikine River. Upton overwintered in Atlin, British Columbia before resuming his trek in June of 1959.

Upton was asked why he took the trip and he responded that he might write a book before turning attention to his brother: “This trip isn’t so much some ways. My youngest brother left Death Valley at the same time for Argentina on horseback.”[2]

[1] Newspaper accounts say he made it to the “vicinity of the mountain” on August 15, 1959.

[2] Upton’s brother left Death Valley at the same time, traveling to Argentina’s Anconcagua (highest mountain in Western Hemisphere—22,837 feet). The expedition only made it to northern Mexico before turning back.

Last updated: February 3, 2025