Part of a series of articles titled Democracy Limited: The Suffrage "Prison Special" Tour of 1919.

Article

Democracy Limited: The Prison Special

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/99471559).

“We do not like to do this, but it seems to be the only way to arouse the Nation and awaken the consciousness of the people to the justice of our cause.” —Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer

"From prison to people": The Prison Special

By the end of 1918, picketers expected to be arrested and almost all leaders of the National Woman’s Party had been in jail for some amount of time. Alice Paul received a 7-month sentence, the longest of any suffragist, followed closely by her second-in-command,Lucy Burns, who received 6 months. During their prison stays, the women faced emotional and physical abuse. During the early spring of 1919, 26 of the women who had been imprisoned at Occoquan Workhouse and in DC jails traveled the country by train to share their stories. They called their train the "Democracy Limited," and their tour the "Prison Special." These politically savvy women used their experience as part of their reasoning why women should get the vote. They claimed that that women were mistreated when they were not allowed to participate in government by voting.

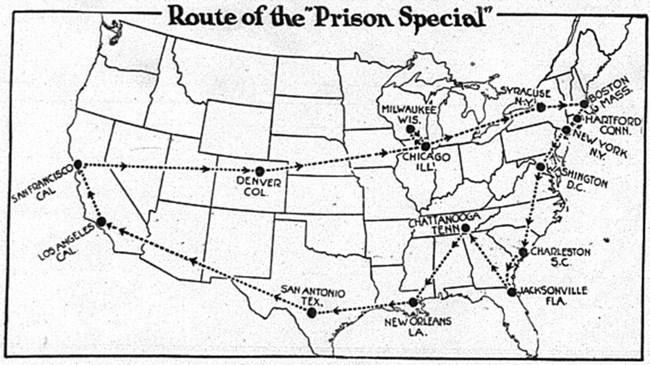

Where did they visit?

The suffragists planned the tour to reach the areas where support was most needed for the suffrage movement. Over three weeks, the suffragists traveled to 15 major cities around the United States. Departing from Union Station in Washington, D.C. in February 1919, the 26 women took the Democracy Limited train to San Antonio, TX and San Francisco, CA, then Denver, CO and Jacksonville, FL. Knowing that the most outspoken opponents to woman suffrage tended to represent more conservative southern states, the organizers of the Prison Special tried to visit southern cities. On February 10th, the women’s suffrage amendment had failed in the Senate by one vote. Suffragists believed that Southern support would be important in securing women’s suffrage nationwide.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000068).

Who participated in the Prison Special?

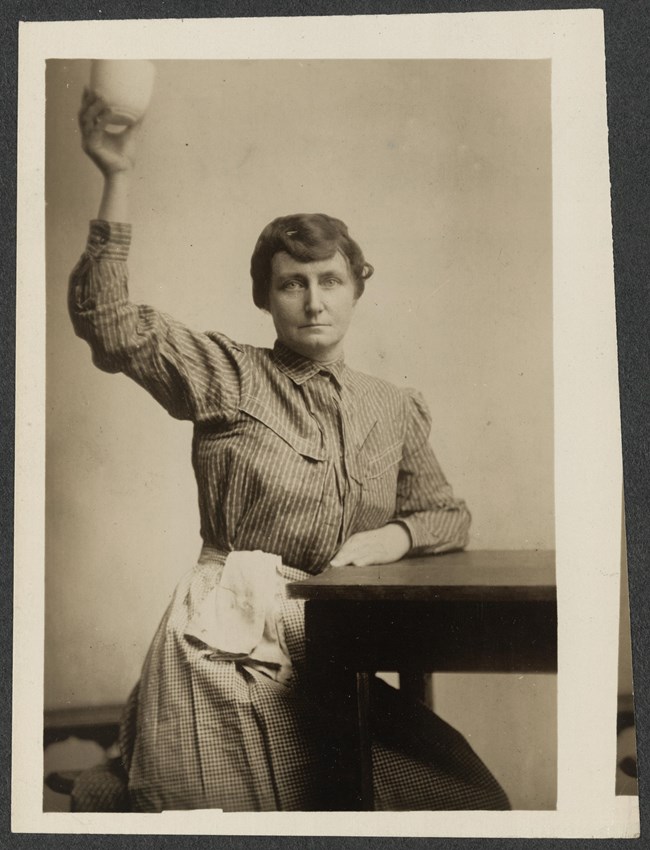

The women who went on tour were all well-educated and well-connected white women. Among these women were Lucy Burns, Pauline Adams, Vida Milholland, Louisine Havemeyer, and others who had lived through the Night of Terror. Wearing recreated versions of the uniform they had worn in jail, the women told stories, gave speeches, and reenacted scenes from prison life. Each woman demonstrated how women were mistreated by the government when they had no say in it.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000247).

Who attended the tour?

In the cities that the tour visited, the Prison Special drew large crowds eager to see the performance and hear the women’s tales. The suffragists on the tour raised money and made connections that helped grow public support for the movement. Even in less sympathetic cities, the suffragists had an impact. Though their stories may not have suddenly changed anti-suffragists’ opinions, they still encouraged anti-suffragists to question their arguments. The Prison Special helped make the conversation about women’s rights and voting laws unavoidable.

What did the tour achieve?

By the time of the tour, arrests of picketing suffragists had ended due to public outrage. Paul’s and the other women’s sentences were overturned. Although we cannot measure the tour’s exact impact, it helped contribute to increasing public support for the women’s suffrage amendment. The following spring, the 19th Amendment was finally passed in both houses of Congress and sent to the states for ratification.

Bibliography

"Detailed Chronology - National Woman's Party History." Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/static/collections/women-of-protest/images/detchron.pdf.

Kelly, Katherine Feo. "Performing Prison: Dress, Modernity, and the Radical Suffrage Body." Fashion Theory 15:3, 299-321. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174111X13028583328801

"Militants Demand a Special Session." New York Times. March 11, 1919. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1919/03/11/97084088.pdf.

O'Gan, Patri. "Traveling for Suffrage Part 4: Riding the Rails." National Museum of American History, March 24, 2014. https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2014/03/traveling-for-suffrage-part-4-riding-the-rails.html.

Palczewski, Catherine H. "The 1919 Prison Special: Constituting White Women's Citizenship." Quarterly Journal of Speech 102:2, 107-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2016.1154185.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. New York: Boni & Liveright, 1920.

by Brianna Nuñez-Franklin

Last updated: May 21, 2020