Last updated: July 6, 2023

Article

Confederate Occupation of Fort Sumter

Library of Congress

During the first two years of Confederate occupation of Fort Sumter, the war raged on other battlefields. However, on April 7, 1863, the war came again to Fort Sumter with an attack by nine Union Navy ironclads, and life in the fort over the next two years changed dramatically.

Conditions at Fort Sumter upon Confederate Occupation

When Confederate troops marched into the fort on the afternoon of April 14, 1861, over 3,300 shells and “hot shot” had been fired at the fort during the initial 34-hour bombardment by 43 Confederate guns. The terreplein (top level) was a wreck, and the parade ground was pitted with shell craters. The enlisted barracks were gutted from fires still burning. The officer quarters were a shambles. However, the outer walls were not damaged significantly.Repairs and Improvements

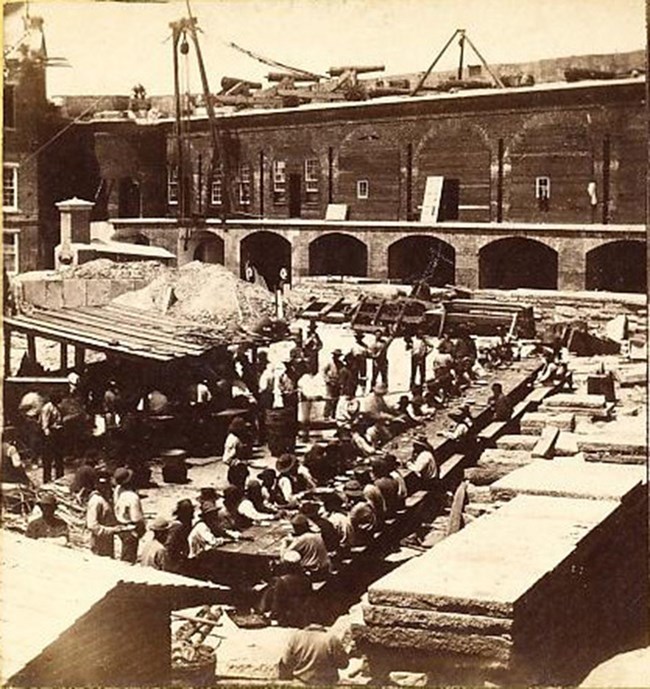

The soldiers, along with civilian and enslaved laborers, immediately got to work extinguishing fires and repairing damage. Over the next weeks and months, work centered on restoring buildings, casemates, and magazines. Additional cannons and mortars were mounted bringing the total to 92, and other improvements were made including:• Structures – The incomplete embrasures (or gun ports) on the upper casemates were bricked in (except for three on the salient) leaving only narrow loopholes for small arms fire. Damage from shells was repaired. Burned out barracks were partially rebuilt but to a lower level, the magazines were strengthened, and the two hot shot furnaces restored.

• Communications – A telegraphic connection was established with Confederate headquarters by way of James Island. A submerged telegraphic cable (or submarine cable) was also completed between Sumter and Fort Moultrie.

• Food Supply – Fresh produce, meats, and other goods were brought from the city by boat to supplement the normal rations of bacon, pork, flour, rice, and meal. A bakery was supplied and was said to have used the two hot shot furnaces.

• Water Supply – The drainage system to collect rainwater to feed the five cisterns (totaling some 25,100 gallons) was repaired. A machine for converting salt water into fresh water by distilling the salt water in a boiler was provided to supplement the cisterns. Water was also transported from the city by boat.

• Lighting – Candles and oil lamps were certainly a primary source of light. However, a major improvement to the fort was a gas-works that supplied gas lighting to several places within the fort. The remnants of a gas line can be seen in the wall near the magazine. The gas-works was most likely of the type used on local plantations to vaporize pine rosin, and then pressurize the vapors (or gas) to force feed the supply lines to the light fixtures.

• Other improvements included a forge for metalworking, a shoe factory, and a fire engine.

Keith Brady Collection

Daily Life 1861 - 63

While the fort was designed to house 650 officers and soldiers, somewhere between 300 and 550 Confederates manned the fort during the first two years of the war. Garrison life was relatively peaceful and routine. Initially, the arming of more cannons plus the repair and improvement work consumed part of their time even though the heavy labor was conducted by work crews comprised largely of enslaved people from local plantations. Training in gunnery, military drills, and other defensive measures were the mainstay of the soldiers’ work days.Entertainment was limited. Social life was restricted to off-duty soldier pastimes, such as letter writing, board and card games, music, and storytelling. Leave passes to the city and occasional visits to home were highly sought after. A highlight was weekend visits by citizens to include ladies bringing picnics and offering conversation and a change from the drudgery of training and daily garrison life.

Keith Brady Collection

Bombardment 1863 - 65

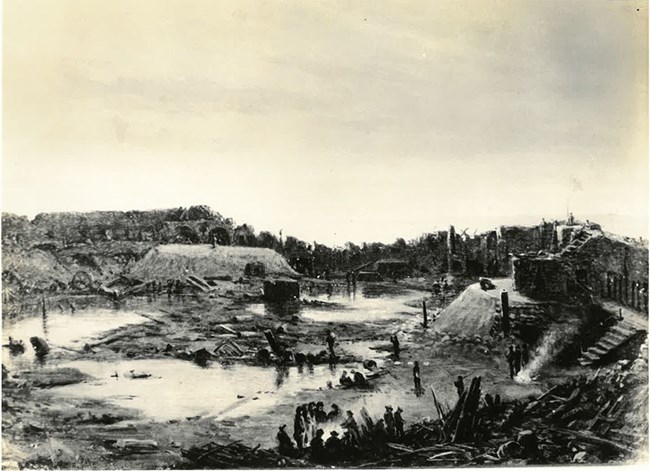

On April 7, 1863, the war returned to Charleston Harbor when the US Navy, with a fleet of nine ironclads, attacked Fort Sumter. While the attack was repelled, and the damage from this two and one-half hour engagement was light, it was a wake-up call.Following this attack, preparations were immediately undertaken to strengthen the fort against further attack by heavier and longer range Union artillery. Between the ironclad attack in April and the first bombardment in August, these efforts were intense, with as many as 450 mechanics and laborers engaged. The upper and lower casemates of the right flank (or sea wall) and the upper and lower rooms of the gorge wall were filled with sand and wetted cotton bales. These reinforcement efforts also included the building of bombproofs (or bomb shelters) and, later, communication tunnels. While debris from the shelling played a role in the ongoing strengthening efforts, new materials hauled in night after night constituted the bulk of the repair and reinforcement.

Repairs continued on a daily basis throughout the 18-month Union bombardment, which began on August 12, 1863. From August 1863 to February 1865, there were three major and eight minor bombardments from US Army artillery located on Morris Island and the US Navy blockade fleet. The fort was under direct fire a total of 280 days during that 18-month timeframe. It was to be the longest siege under fire in US military history. Over 46,000 projectiles were fired against it with an estimated total weight in metal of 3,500 tons.

Confederate soldiers suffered at least 52 killed and 267 wounded. The exact number of civilian and enslaved casualties was not carefully documented and thus remains unknown, although undoubtedly significant and thought to be roughly proportionate to the soldier casualties.