In October my brother and myself spent a vacation of several weeks at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, experimenting with a soaring machine...It is the ideal place for gliding experiments except for its inaccessibility. Wilbur Wright, 1900

The Wright Brothers National Memorial is recognized as the site of the first successful human attempt at heavier-than-air, controlled, powered flight carried out by Orville and Wilbur Wright on December 17, 1903. There is little doubt that what the brothers achieved on the windswept dunes of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina from 1900 to 1903 changed our world forever. However, the steps taken to commemorate the brothers’ achievements are in many ways as remarkable as the achievements themselves. The commemoration of their success at Kitty Hawk not only provides a place for visitors to reflect on and be inspired by the dream of flight; it ironically forever helped to alter the Outer Banks relative isolation, isolation that the brothers strongly desired for their flying experiments.

Wind, Sand, and Isolation

In 1900, the brothers consulted the U.S. Weather Bureau and other individuals conducting flight experiments to identify locations that would meet certain criteria of topography, vegetation, and wind (a wide, open space; steady winds of fifteen to sixteen miles per hour; isolation; elevation change; and soft sand for landing). They chose the North Carolina Outer Banks because the landscape was characterized by broad, open expanses of shifting sand and steady northeasterly prevailing winds. The area was void of vegetation because of the high winds, salt spray, and periodic storm overwash. Following correspondence with the limited residents of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Orville and Wilbur Wright were persuaded that this was the best location for their flight experiments, due to the presence of several large sand dunes, known in the area as Kill Devil Hills.

After the brothers’ first successful powered flights on December 17, 1903, they returned to their hometown of Dayton, Ohio to continue their flying experiments in 1904 and 1905. It was not until 1908 that the brothers returned to the isolation of the Outer Banks, using the steady winds to prepare their aircraft for what would soon be demonstrations for the U.S. Army and French clients.

By the end of May, 1908, the brothers were confident they could meet the required demonstrations the contracts called for. Wilbur left the Outer Banks on May 17 for Europe, where he began assembling the aircraft for the demonstration in LeMans, France. Orville left camp a few days later for Dayton to begin building a new flyer for the U.S. Signal Corps tests at Fort Myer, Virginia. In 1911, Orville returned to Kitty Hawk (sans Wilbur) for a short period for further gliding experiments. Wilbur died in 1912 of typhoid fever.

Initial Recognition of the Wrights’ Efforts

The LeMans and Fort Myer tests received wide acknowledgment as resounding successes. By 1909, the Wrights led the world in the piloting and production of airplanes, but their standing was not universally accepted at the time. For many years they faced a number of contenders for priority in aeronautics, especially the American aviator Glenn Curtiss, whose independent development of ailerons eventually superseded the Wrights’ wing-warping mechanism.

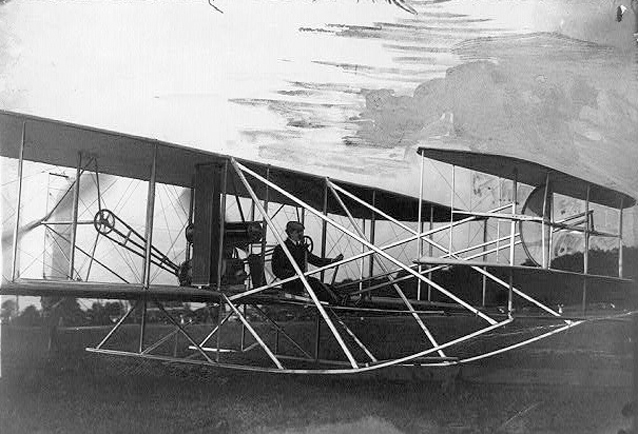

George Grantham Bain Collection- Library of Congress

World War I highlighted the Wrights’ contributions to the development of flight. For example, the U.S. air division, which started with Wright-supplied Signal Corps aircraft in 1917, grew to a force of 13,000 planes, with orders pending for 52,000 more.

By the mid 1920s, a period of renewed interest in flight culminated with Charles A. Lindbergh’s nonstop flight from New York to Paris in May, 1927. The increased flight activity of the late 1920s encouraged a public recognition of the Wrights’ place in the history of aviation. At the local level, North Carolinians, led by W.O. Saunders sought to memorialize the site of the Wrights’ experiments and to underscore the importance of the Outer Banks to their success. Saunders, the editor of the Elizabeth City Independent, organized the Kill Devil Hill Memorial Association to ensure a proper commemoration of the Wrights’ first flight effort. A longstanding champion of Outer Banks causes, Saunders progressively pushed for economic development, with a memorial to the Wright brothers seen as part of that development. Other important players included Frank Stick, a real estate developer from New Jersey interested in promoting the Outer Banks, and North Carolina administrators and politicians such as Frank Page of the North Carolina Highway Commission and R. Bruce Etheridge, Director of the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development.

National figures joined local efforts to promote the idea of a memorial. U.S. Representative Lindsay Warren of North Carolina first introduced a bill for a Wright memorial to Congress on December 17, 1926, the twenty-third anniversary of the first flight. Senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut introduced a similar bill in the Senate the same day. Representative Warren enlisted the support of Orville Wright and the National Aeronautics Association. Frank Stick and other New Jersey investors donated the land at Kill Devil Hills. The act passed both houses of Congress and was signed by President Calvin Coolidge on March 2, 1927, establishing the Kill Devil Hill National Memorial.

Idea For a Monument

The specifics of the Wright Brothers Memorial Act called for a monument to be erected in honor of the brothers’ achievements at Kitty Hawk. As governmental members debated the design and location of the memorial, the Kill Devil Hills Memorial Association lobbied for construction of a bridge to the Outer Banks (completed in 1930) and a new road connecting Kitty Hawk and Nags Head. The memorial offered an incentive for tourists to visit the area, and therefore provided a justification for new roads and bridges.

The Office of the Quartermaster General prepared a report in October 1928 suggesting that the top of the largest hill (Kill Devil Hill) would be a suitable location for the monument. Previously, it had been thought that such an attempt would be impractical because of the shifting sands on the dune, but a committee appointed to investigate the site discovered that the hill consisted of moist and heavily compacted sand, which could be planted and secured. By this time nothing remained of the camp buildings constructed by the Wrights, and the prevailing winds had caused the southwestward migration of Kill Devil Hill by approximately 450 feet. In 1928, the Coast Guard and local citizens began the first stabilization efforts of Kill Devil Hill, planting shrubs and sand grass around its bases and on its slopes.

Wright State University Archives

First On-Site Commemoration

An important first step in the realization of the Wright Brothers National Memorial occurred on December 17, 1928, when 200 delegates from the International Civil Aeronautics Conference and more than 3,000 visitors dedicated a granite marker placed at the approximate location of the 1903 liftoff and laid the cornerstone of the monument to be placed on Kill Devil Hill. W.O. Saunders, Senator Hiram Bingham, and Secretary of War Dwight Davis addressed the crowd, including Orville Wright and Amelia Earhart. The National Aeronautics Association provided the marker, carved to resemble a boulder.

National Park Service Archives

Designing and Placing the Monument

In June 1928, the Office of the Quartermaster General announced a competition for designing the monument. The winning design, by New York architectural firm Rodgers & Poor, was an Art Deco-inspired masonry shaft and base of 60 feet set on a star-shaped foundation. The triangular shaft was embellished with relief carvings symbolizing stylized sculpted wings on the east and west sides. The design implied ancient Egyptian motifs, an important source for Art Deco designs.

Before construction of the monument began, Kill Devil Hill required additional stabilization. Local and regional plants and grasses were supplied, with stabilization completed in 1931. In addition to halting the westward migration of the hill through stabilization, a wire fence was placed around the base of Kill Devil Hill to prevent tourists, souvenir collectors, and wild hogs from damaging the site.

The Willis and Mafera Corporation of New York began construction of the monument and base in December 1931 and completed their work in November 1932.

Original Park Entrance

To coincide with the construction of the monument, the War Department constructed an entrance feature that was sited to provide a visual link to the First Flight Marker, as well as a view to the monument. Roughly following the form of truncated obelisks, the entrance gateposts used ancient Egyptian motifs like the monument. Just west of the entrance, a small visitor contact station was constructed, with both being completed before the transfer to the National Park Service in 1933.

Transfer to the National Park Service, 1933

In August 1933, two Executive Orders transferred administrative authority over forty-eight areas under the War Department to the National Park Service. Kill Devil Hills Monument National Memorial was one of the forty-eight. Horace Dough, local boat builder and fishing guide, was appointed caretaker a few days before the transfer.

As a result of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, the park received $90,500 through the Public Works Administration for improvements. From 1934 to 1939, many improvements and additions were made to the site, including walking paths, a comfort station, and a superintendent’s residence.

World War II brought development to a halt. A lack of funding forced the National Park Service to cut staff and money was unavailable for the basics, including fertilizer.

1947 Master Plan and Mission 66, 1947-1966

In 1946, with World War II ended, Superintendent Horace Dough asked for exhibits and other improvements to improve the visitor experience. In 1947, the park drew up a master plan that emphasized interpretation and advocated thinning out brush and other vegetation in order to return to a more accurate historic setting.

This master plan included the creation of an east-west entrance road and the removal of the existing north-south entrance road. Perhaps most important, refinements to the 1947 plan in the 1950s included a museum/visitor center that ultimately changed the park’s orientation and focus.

In 1951, the Kill Devil Hills Memorial Association reorganized as a national “Society” hoping to raise awareness about the fiftieth anniversary of the first flight to be celebrated in 1953. The Kill Devil Hills Memorial Society hoped to raise funds for land acquisition, a museum, reconstruction of the camp buildings, and eventually an airstrip. These plans marked a shift from commemoration to comprehensive interpretation in the landscape.

In November 1953, the Avalon and Old Dominion Foundations of New York gave $82,000 for land acquisition at Wright Brothers National Memorial. With the money finally in hand for the needed land purchase, building the museum and new entrance road became the next priority. The 1954 General Development Plan, which included an airstrip east of West Hill, further articulated the implementation of a larger interpretive program for the site.

In October 1957, National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth outlined Mission 66, a ten-year program to transform the American national park system to meet the conditions and demands of the postwar era. The program included a new building type that centralized basic visitor services.

Historic American Buildings Survey- Library of Congress

The 9,900 square foot visitor center was dedicated in December 1960. At this time, the visitor center and camp buildings became the center of comprehensive interpretation, with the suggestion from Washington that the monument be closed to visitors. Staffing was not adequate to man the monument, and there was also a concern about visitor safety.

Definite plans for a 3,000-foot airstrip, to be located on the western edge of the park, were announced at the December 1962 anniversary ceremonies. The dedication of the First Flight airstrip occurred at the sixtieth anniversary celebration in 1963.

In October 1966, Wright Brothers National Memorial was entered into the National Register of Historic Places, subsequent to passage of the National Historic Preservation Act, and documented as a historic district in August 1978.

The Modern Era

In January 2001, the visitor center was designated a National Historic Landmark as a nationally significant example of a Mission 66 visitor center and as one of the most important examples nationally of the Philadelphia School of modernist architecture.

December 17, 2003 marked the 100th anniversary of the first powered flights at Kitty Hawk. Over 30,000 people were in attendance at Wright Brothers National Memorial to commemorate the remarkable achievements of the two brothers from Dayton 100 years before, when the Outer Banks had limited dirt and sand cart paths, a local population of only a few hundred residents, and was only accessible by boat.

But for the brothers’ success at Kitty Hawk from 1900 to 1903 and their subsequent commemoration, the Outer Banks as we know them today, with modern roads, bridges, and commercial and residential development, might not have come to fruition.

National Park Service

Last updated: August 16, 2017