Part of a series of articles titled Cold War Civil Defense: From "Duck and Cover" to “Gun Thy Neighbor”.

Previous: Nelson Rockefeller and Civil Defense

Article

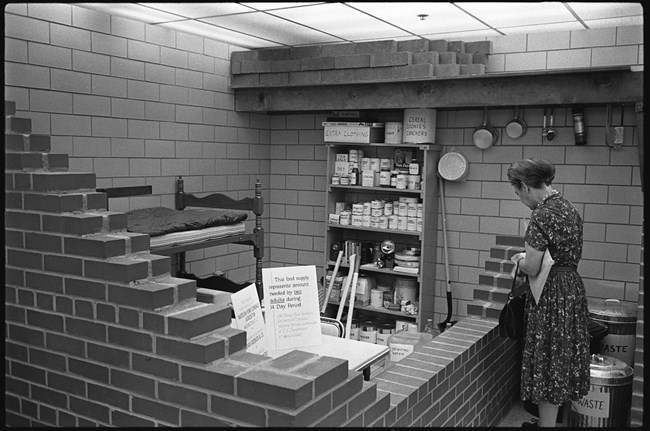

NPS Photo / MIMI 518

In May 1961, as Chair of the Civil Defense Committee of the Conference of Governors, Nelson Rockefeller met with President Kennedy to advocate for a national fallout shelter program. Two weeks later, Kennedy addressed a joint session of Congress, noting the “apathy, indifference, and skepticism” surrounding civil defense policy and asking for appropriations for “a much strengthened Federal-State civil defense program” that would include both public and private fallout shelter construction. Kennedy’s receptivity to Rockefeller’s agenda is believed to have arisen from the threat Rockefeller posed as the presumptive Republican nominee in the upcoming 1964 presidential election. Because his popular rival was so closely identified with civil defense, it has been suggested, Kennedy could not afford to appear weak on the issue. In the following month, the confrontation between the US and USSR over Allied occupation of Berlin led to the highest state of tension to date between the two powers and brought the question of civil defense to the national forefront. In his July 25 radio and television address about the Berlin Crisis, Kennedy presented the standoff as a national emergency and implied that nuclear war was a real possibility. He reiterated his commitment to a fallout shelter program, pledging to “let every citizen know what steps he can take without delay to protect his family in case of attack.” In October Kennedy called for “fallout protection for every American as rapidly as possible.” At the same time Kennedy was encouraging private shelter construction he asked for a $207 million appropriation from Congress for the first (and only) large-scale public shelter program proposed at the federal level, for the identification, labelling, and stocking of shelters in existing buildings.

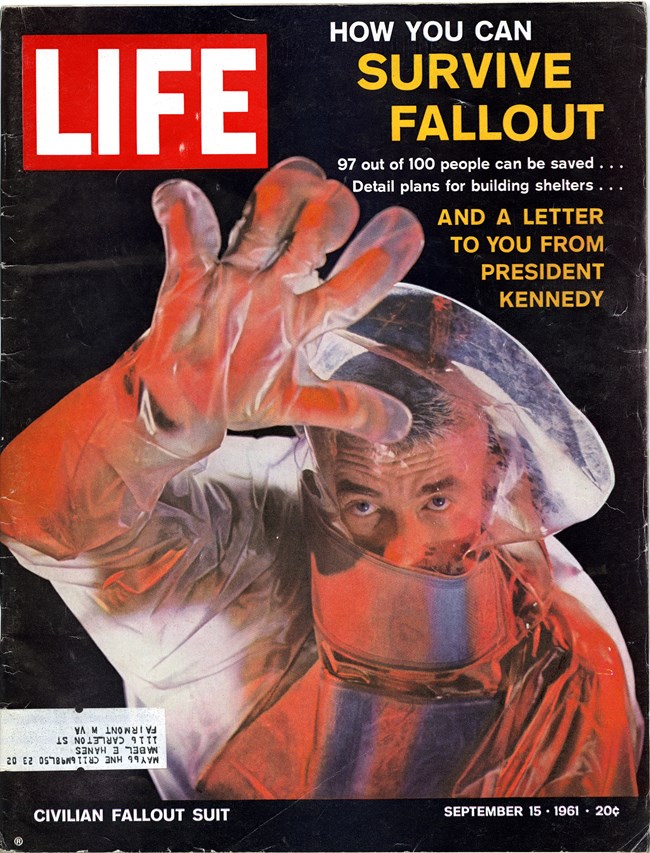

Public interest in family shelters surged, and businesses—frequently, repurposed building-supply retailers or construction contractors—sprang up, offering kits and prefabricated shelters and displaying models in shopping centers nationwide. Family fallout shelters also received a flurry of media attention. The September 1961 issue of Life Magazine featured a cover story titled “You Can Protect Yourself from Nuclear Attack” containing a letter from President Kennedy that encouraged family shelter construction, and optimistically projecting that fallout shelters would allow 97% of the US population to survive a nuclear attack.

In the popular press and academic journals, intellectuals, scientists, clergy members, and liberal (and some conservative) editorialists denounced Kennedy’s call for private fallout shelter construction. An influential article in Time magazine in August 1961 titled “Gun Thy Neighbor” examined the ethical question of private family shelters, citing a trend of secretive, armed shelter owners and quoting a “Chicago suburbanite” who stated, “When I get my shelter finished, I’m going to mount a machine gun at the hatch to keep the neighbors out if the bomb falls… If the stupid American public will not do what they have to to save themselves, I’m not going to run the risk of not being able to use the shelter I’ve taken the trouble to provide my own family.” The article quoted a number of clergymen who weighed in on the moral implications of private shelter ownership, demonstrating the civic conundrum that would result when survival became the responsibility of individual citizens who would have to decide whether to include others at the expense of their own family’s survival . Others criticized the inequity of recommendations that were aimed primarily at suburban homeowners (at that time, almost exclusively white), specifically those with money for discretionary construction. When asked by the administration to comment on a draft of the Kennedy booklet that encouraged private shelter construction, economist John Kenneth Galbraith quipped that the shelters were a “design for saving Republicans and sacrificing Democrats.”

Critics also questioned, as they had for Nelson Rockefeller’s proposed state legislation, whether widespread shelter building and the promise of civilian survival would increase the probability of nuclear war instead of deterring it, making the US and Soviets more (and not less) willing to launch a nuclear strike. Although shelters might save individual lives in a nuclear conflict, it was reasoned, if they helped catalyze the conflict they would be responsible for a net increase in deaths. Also questioned was the feasibility of postwar life in the contaminated world that families would emerge into after their two-week shelter stay. Furthermore, it was asked, what would prevent the Soviets from launching a follow-up attack at that precise moment to finish off the previously-sheltered population?

Scientists disputed the efficacy of fallout shelters as a strategy for mass survival, pointing out that the limited urban attack scenarios described to the public were hypothetical and based on many variables—the number and tonnage of weapons launched, the height and location of the detonation (groundburst or airburst? Population center or military installation?), the accuracy of deployment—that were selectively chosen to describe a best-case outcome in which most of the population was far removed from blast effects and had ample time to seek shelter from fallout. The incendiary power of explosions, scientists hypothesized, could cause firestorms for miles beyond the radius affected by the immediate blast, turning fallout shelters into deathtraps. While fallout shelters might provide safety if located well outside of the area of these effects, not knowing where and how large the detonations would be meant that shelters could not guarantee survival in any location. A Consumer Reports article offering Americans guidance about whether to build a shelter noted that instead of providing “insurance” against a nuclear attack as government materials claimed, building a fallout shelter was more aptly described as a bet—a wager that circumstances would happen to favor survival inside a basic shelter that only offered fallout shielding.

Library of Congress (LC-DIG-ds-07442)

Although the question of whether to build a shelter was an omnipresent conversational topic in many suburban households and communities in 1961, Americans themselves largely rejected the proposition. This was reflected in both contemporary polling and estimates of actual shelter construction. A 1961 Gallup poll revealed that 93% of Americans had no plans to build a shelter. An opinion poll of New York State residents, and a nationwide poll conducted by Columbia University found similar disinclination towards shelter construction, citing the high costs, not having space, and not being property owners. A US News survey and New York Times reporting also noted that despite shelter-building being much-discussed and foremost in most Americans’ mind, attitudes of apathy and fatalism prevailed. Although families believed that nuclear war was a definite possibility, in addition to the practical problem of affordability they questioned the effectiveness of fallout shelters, the moral question of having to exclude others, and whether a life in the aftermath of a nuclear war would be worth living. This resistant mindset is captured in Bob Dylan’s 1962 song Let Me Die in My Footsteps that exhorted fully living in the present and rejecting sheltering: “And if this war comes and death’s all around / Let me die on this land ‘fore I die underground.”

The polling data aligns with the estimated numbers of actual private shelters that were built. Although an accurate count is elusive, as many who did construct them were not eager to advertise this fact, by 1965 there were an estimated 200,000 in the US, up from 60,000 in June 1961 and just 1565 in March 1960. While not insubstantial, this number represented just one shelter for every 266 households, or 0.4 % of homes, a far cry from the widely sheltered populace that Rockefeller and others had envisioned and that newly-formed shelter companies were anticipating. In the years following 1961, 600 fallout shelter companies would file for bankruptcy.

NPS Photo / MIMI 2855

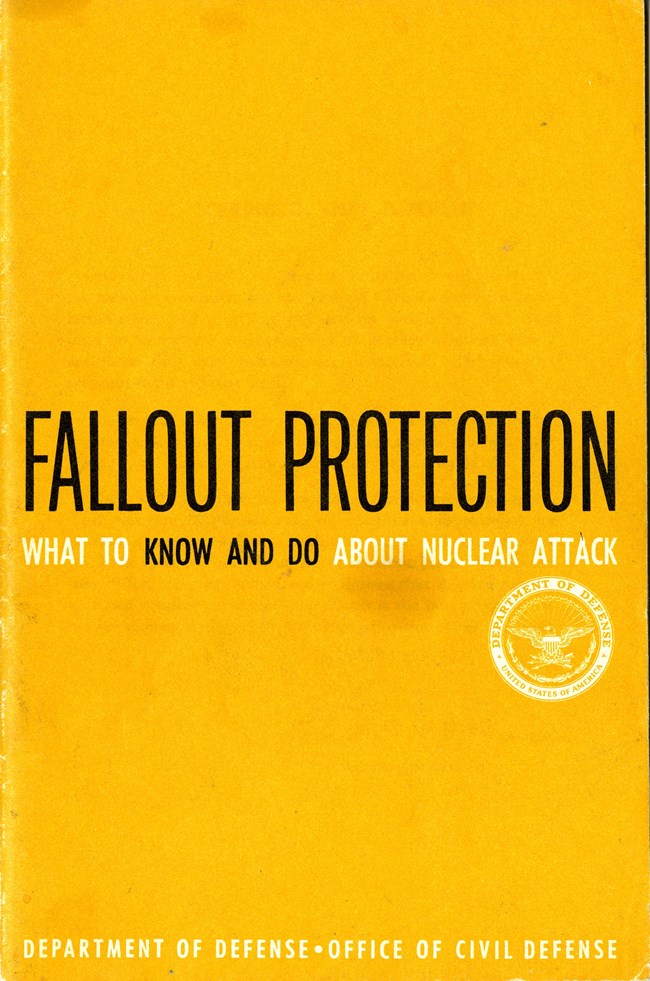

The Kennedy administration itself had doubts about the wisdom of continuing to officially encourage private shelter building in the manner promoted by Governor Rockefeller. After discussing the matter with advisors over the 1961 Thanksgiving weekend, Kennedy decided to shift his administration’s focus away from family shelters, worried about the economic, geographic, and racial inequities implicit in a civil defense program that promoted private shelter construction, and also about the “gun thy neighbor” ethical controversy of private shelter ownership. Despite the 1962 publication of “Fallout Protection: What to Know and Do About Nuclear Attack,” a booklet in the model of Eisenhower’s and Rockefeller’s earlier pamphlets that discussed both family and public shelters and an associated book of family shelter designs, private shelter building would be deemphasized in the Kennedy administration’s civil defense agenda as it focused on the National Fallout Shelter Survey and Marking Program. This initiative to identify, label, and stock public shelters in existing structures was also established in 1961 and was underway in 1962.

In November 1961, too, Nelson Rockefeller would finally see civil defense legislation passed in New York state, funding shelters in State buildings, schools and colleges, and giving a property tax exemption to individuals who constructed private shelters on their property. Rockefeller’s shelter legislation was never widely enacted, however; soon after its passage the public learned that Joseph Carlino, the assembly speaker who had sponsored the bill had ownership in a fallout shelter company, resulting in a conflict-of-interest scandal and public protest.

In December 1961 Kennedy wrote Rockefeller with a tone of dismissive finality to thank him for the “advice and assistance you have given in shaping the program on civil defense which I shall present to the Congress next year” and noting that it was being taken over by the Department of Defense. Over the next years in the National Fallout Shelter Survey and Marking Program, administered by state and local government civil defense offices, architects and engineers were contracted to survey existing public and private structures, utilizing standards developed during the Eisenhower administration to determine which had spaces that met the requirements for fallout protection and how those that did not could be modified for inclusion. The identified buildings were marked with location and capacity signage, whose familiar orange and black signs are still seen on some buildings today. About one-third were eventually stocked with two-week supplies of federally-supplied water stores, “survival biscuits,” medical and sanitation kits, and radiation detection meters. Supply stocking, beset with logistical challenges, began shortly before the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, an event which revealed how few of the designated shelters were ready for habitation. Citizens were trained to populate and manage the shelters in the event that they became necessary. Active surveying, stocking, and staffing would continue through 1970. By 1974, the program was allowed to lapse and municipalities would be faced with the problem in the coming years of disposing of the biscuits and supplies.

In April 1962 Nelson Rockefeller was informed by his advisers that for some time “considerable public opinion [had] ranged against both the federal and New York State fallout shelter programs,” and would not take up the matter again in his career.

Although Rockefeller’s efforts to require the construction of a family-based fallout shelter system were ultimately unsuccessful, largely rejected by a public who was unable to shoulder the financial responsibility and unwilling to accept the premises of a survivable nuclear war, he did bring the issue to national attention, incurring lively debate in national discourse and also identifying him inseparably with the concept. There is no doubt that Nelson Rockefeller’s insistence and omnipresence on the issue influenced the existence of the Kennedy public shelter program.

Part of a series of articles titled Cold War Civil Defense: From "Duck and Cover" to “Gun Thy Neighbor”.

Previous: Nelson Rockefeller and Civil Defense

Last updated: November 4, 2021