Last updated: May 9, 2023

Article

Chicago's Black Metropolis: Understanding History Through a Historic Place (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

Imagine an early spring day in the city of Chicago--cold and rainy, windy with overcast skies. Activity fills the streets as people come and go, school buses fill up and pull away, trucks and cars line up behind traffic lights and then move on. Ringing rhythms of hammers and the screeching of power saws dominate the sounds of the city. Some workmen repair, restore, and build anew, while others demolish old structures and haul away the debris. Large housing projects and institutions take up much of the land in this area of the South Side of Chicago. But between them there is a gap where old buildings survive, all that remains of an area that was called Black Metropolis.

There is a Victory Monument here, celebrating African American contributions to the Allied victory in World War I. Other nearby structures, such as a newspaper building, an office and manufacturing building, and a YMCA, also testify to the presence of thousands of African Americans who came to Chicago's South Side in the early 20th century to fashion a better life for themselves and their families. The search for the history in these places leads to questions about the essence of history itself: What happened here? Why did the place change? What has transformed the site into a historically important place? How am I connected to this place?

About This Lesson

The lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file "Black Metropolis Thematic Nomination" and several other primary and secondary sources. It was written by Gerald A. Danzer, professor of history at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Adrian Capehart, Dee Woodtor and Harold Lucas kindly provided personal insight into Chicago's Black Metropolis. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in units on early 20th-century urban history, especially the migration of African Americans to the city. The lesson will help students develop skills of historical thinking and reflect on the value of historic preservation.

Time period: 1900-1929

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Chicago's Black Metropolis: Understanding History through a Historic Place relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

- Standard 2B- The student understands the first era of American urbanization.

Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

-

Standard 1B- The student understands the rapid growth of cities and how urban life changed.

-

Standard 2B- The student understands "scientific racism", race relations, and the struggle for equal rights.

-

Standard 2A- The student understands the sources and experiences of the new immigrants.Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

-

Standard 1C- The student understands the limitations of Progressivism and the alternatives offered by various groups.

- Standard 3B- The student understands how a modern capitalist economy emerged in the 1920s.

Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

-

Standard 1B- The student understands how American life changed during the 1930s.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Chicago's Black Metropolis: Understanding History Through a Historic Place

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard E -develop critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

-

Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced, physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

-

Standard D - The student describes the role that supply and demand, price incentives, and profits play in determining what is produced and distributed in a competitive market system.

-

Standard I - The student uses economic concepts to help explain historical and current developments and issues in local, national, or global contexts.

Objectives for students

1) To place the historic Black Metropolis in the changing urban pattern of Chicago.

2) To identify key events in the history of the Black Metropolis.

3) To explain how the surviving buildings reflect the history of the Black Metropolis.

4) To apply the process of historical inquiry to their own community to identify special historic places that might merit official recognition.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied and distributed to students. The maps and photographs appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

1) Three maps of the U.S., Chicago, and the Black Metropolis;

2) One reading from the National Register of Historic Places nomination form for Black Metropolis; and

3) Three photos and two drawings of the Black Metropolis.

Visiting the Site

The Black Metropolis Convention and Tourism Council operates a Bronzeville Visitor Information Center that acts as the interpretive center for the Black Metropolis. The information center is located in the Supreme Life Building, at 3500 S. King Drive, on the southeast corner of the intersection with 35th Street.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What might this drawing represent?

Setting the Stage

Even though we take for granted our right to choose where and how we live, most African Americans have ancestors who were denied these fundamental rights. These individuals, who came to America in chains as slaves, were regarded as personal property. As a result, slaves were rootless, subject to being moved and sold at their owner's whim. After the Civil War, former slaves theoretically were free to go where they pleased, but realistically had few choices.

The growth of large industrial cities in the North, with their demand for cheap labor, opened up opportunities over the years. By the early 20th century, the migration of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North had become a regular flow. The peak period of this movement, known as the Great Migration, occurred during World War I when increasing demands placed on Northern industry coincided with the halt of immigration from Europe, a primary source for new workers, due to wartime conditions.

The creation of Chicago's Black Metropolis, also known as Douglas and Bronzeville, was part of this story. It was largely created by the Great Migration, sustained by a continuing influx of newcomers over the years, and put through times of trial during the Great Depression and the urban renewals of the 1950s and 1960s.

Locating the Site

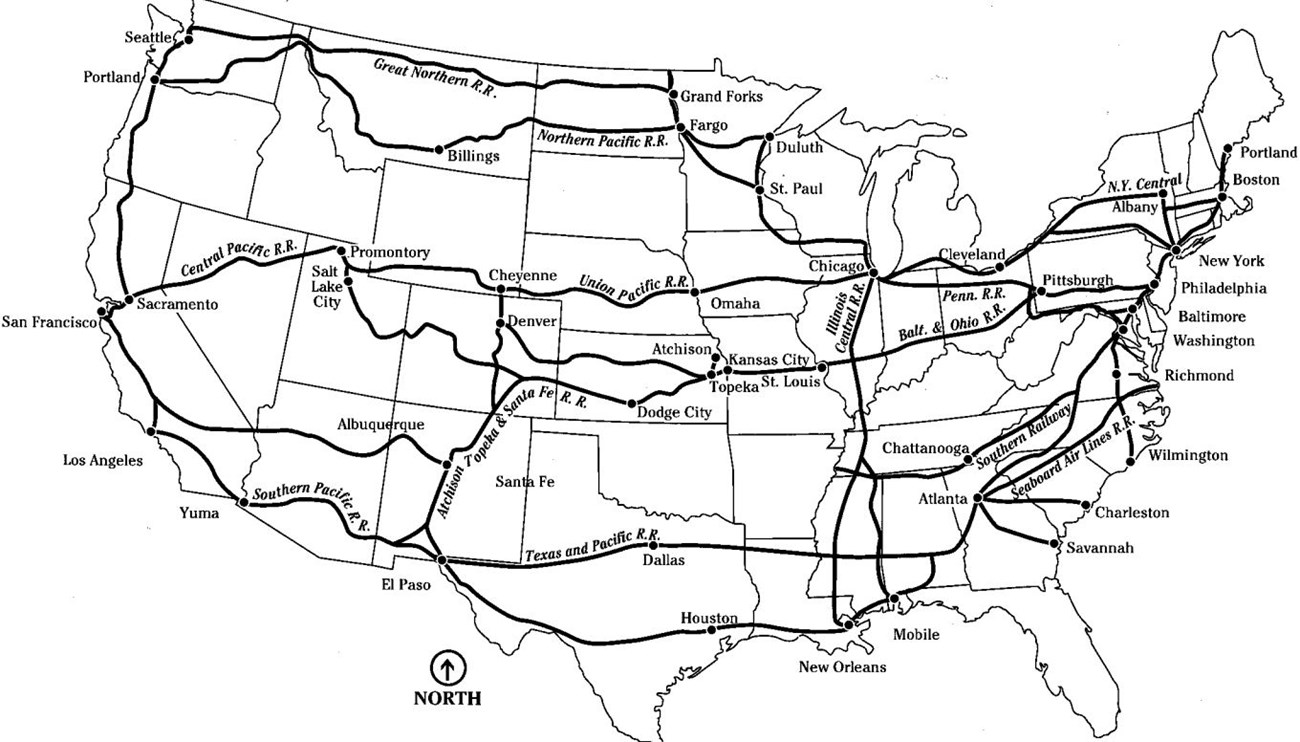

Map 1: Major Railroads in the U.S., 1900.

The Illinois Central was a trailblazing railroad that led from the mouth of the Ohio River to Chicago. Southern extensions carried its tracks to Mobile and New Orleans. Constructed in the 1850s, it was at that time the longest railroad in the world and the first one to be financed by major land grants from the federal government. Stephen A. Douglas, a Democratic leader in the 1850s, sponsored the railroad as one aspect of his plan to hold the nation together during that decade of crisis.

1. Locate Chicago. Why do you think the city became a focal point for the emerging railroad network in the 19th century?

2. What do you notice about the direction in which most of the railroads run? What do you notice about the direction of the Illinois Central?

3. What impact do you think this railroad would have had on the Great Migration?

Locating the Site

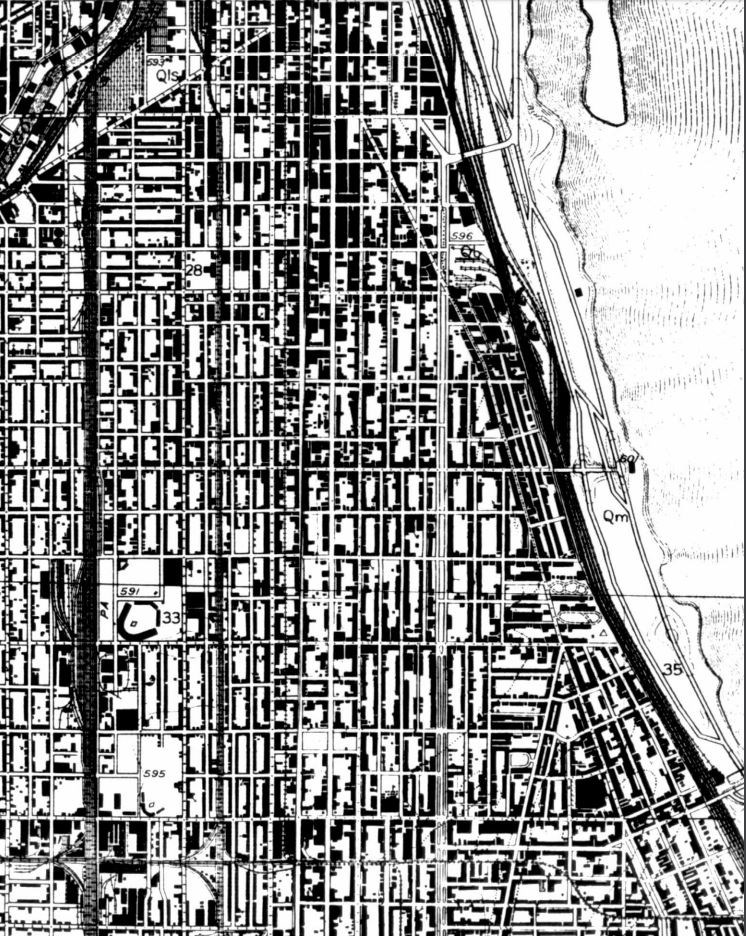

Map 2: Chicago's Black Metropolis and surrounding area, 1920s.

As in most parts of the U.S., Chicago's African American community was concentrated in certain areas rather than being assimilated into the city at large. From the middle of the 1800s, one of the largest concentrations of blacks was south of the main business district in an area known as the Near South Side. Around the turn of the century, the number of blacks in this neighborhood expanded rapidly, primarily as the result of migration from the South. The resulting community, whose borders also grew, became known as "Black Metropolis" or "Bronzeville."

Why do you think blacks were concentrated in certain sections of Chicago?

Locating the Site

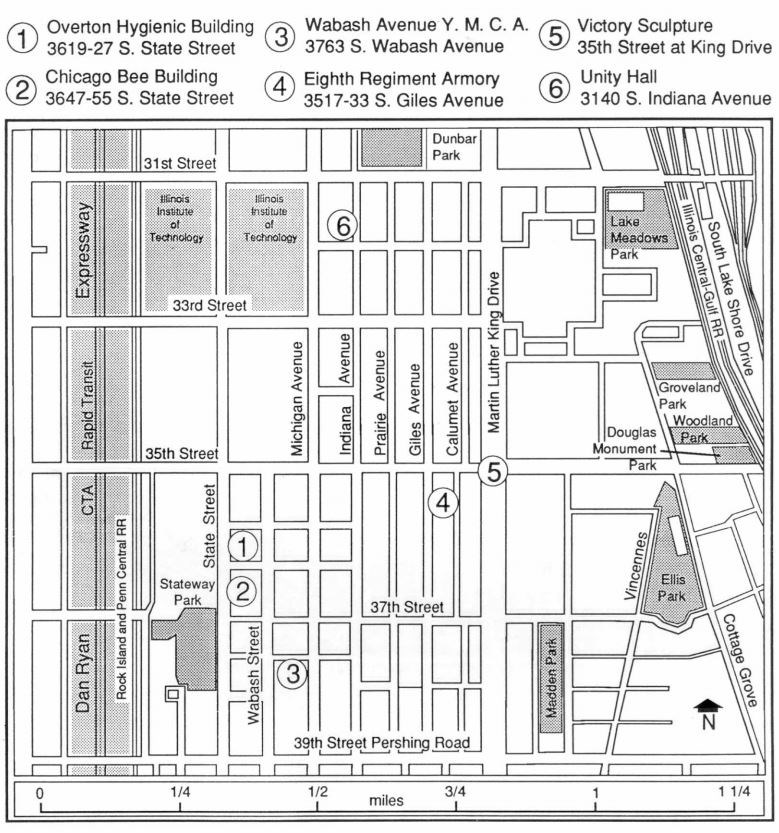

Map 3: Historic Places in the Black Metropolis Today.

This map indicates the locations of six surviving historic buildings in the Black Metropolis that were nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. The National Register is the nation's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that are deemed worthy of preservation. The commercial center of the community was located along State Street, between 35th and 39th streets.

1) Match the map to the corresponding area on Map 2 by locating Thirty-fifth and State Streets on each.

2) Find and highlight these two large housing developments:

a) Lake Meadows, a high-rent complex which lies close to Lake Michigan bounded by Thirty-first Street; Martin Luther King Jr. Drive; Thirty-fifth Street; Cottage Grove; Thirty-third Street; and the railroad tracks.

b) Stateway Gardens "Public Housing Project," which occupies the area south of Thirty-fifth Street to Pershing Road between the Interstate Corridor and State Street.

These areas were substantially redeveloped after World War II. To discover buildings associated with the center of Black Metropolis in the 1920s through the 1940s, we must look in the gap between these more recent developments.

3) Why do you think existing buildings might have been torn down to build these housing developments?

For high resolutions, see the following links:

Determining the Facts

Reading: The Significance of Black Metropolis

Instructions for educators:

The next reading is a portion of the form the Commission on Chicago Landmarks used to nominate the six structures shown on Map 3 for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. The National Register is the nation's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that are deemed worthy of preservation. To be listed, a site must be identified as significant to understanding the historical and cultural foundations of the nation. Both the National Register list itself and the nomination forms are excellent sources of information for individuals seeking the history of a community.

Divide the class into nine groups and have each group read the first paragraph and answer the corresponding questions. Next assign each group one to two paragraphs from numbers 2 through 10 and have them answer the appropriate questions for the paragraph(s) they have read. Ask students to come up with an identifying title for their paragraph(s). Then have all students read paragraphs 11 and 12 and answer those questions as well. Finally, have the whole class discuss how each individual paragraph contributes to an overall understanding of the place and its importance. Ask them to consider how this example could be used as a model for investigating other places and deciding whether those places are historic.

Paragraph 1

1. What does the introduction suggest as the major theme represented by the nominated buildings and monument?

2. What is meant by a "city-within-a-city"?

3. Describe some "restrictions, exploitations, and indifference" that blacks might have experienced in other parts of the city in the early 20th century.

4. What does it mean that Black Metropolis was built "from the ground up" by its own enterprise and capital?

Paragraph 2

1. Create a time line using the dates mentioned in this paragraph. Relate these dates to the founding of Chicago in 1833 and to the Civil War.

2. What did the publication of The Colored Men's Professional and Business Directory indicate about the development of the black community?

Paragraphs 3 and 4

1. What are some reasons why a particular community might become a "city-within-a-city"?

2. Look up the definition of "entrepreneur." In what respects was Jesse Binga an entrepreneur?

3. Suggest some things that might have been "impediments to growth" for Chicago's black community in 1900. Do these exist in any form today?

4. What was the Great Migration?

5. How much did Chicago's Black Metropolis grow in absolute numbers between 1900 and 1920?

Paragraph 5

1. What does the phrase "Wall Street of the black community" mean?

2. List the various types of businesses clustered at the center of Black Metropolis. Which ones suggest a "Wall Street" image?

3. When was the "boomtime" for this business community?

Paragraph 6

1. Do you think entertainment is an important aspect of community life? Why or why not?

2. Where did the "musical winds" circulating around State and Thirty-fifth Streets originate? Do you think we still feel their breezes today?

Paragraph 7

1. Why does the author combine religious life and social programs in the same paragraph?

2. Use an American history textbook to look up the term "social gospel" and relate it to the content of this paragraph.

3. What is a philanthropist?

Paragraph 8

1. Why did black voters at first work with the white Republican bosses in this district? How did this situation change?

2. Why are 1915 and 1928 significant dates in the story of political leadership in Black Metropolis?

Paragraph 9

1. Before radio and television, the print media played a much larger role in the life of a community than it does today. List some of the leading newspapers and magazines of Black Metropolis. Why did some of these publications appeal to an audience across the nation?

2. How was the Chicago Defender connected to the Great Migration?

Paragraph 10

1. What is an "alternate business area"? How did such a development threaten the traditional center of Black Metropolis?

2. What did black leaders mean by "the self-supporting momentum" of Black Metropolis? Why did they feel this would lead to eventual recognition by Chicago's downtown business establishment?

Paragraphs 11 and 12

1. What is a "skid row"? Why was this term used to describe the Thirty-fifth Street district in 1950?

2. What is urban renewal? When were urban renewal programs put into effect? Use an American history textbook to help develop your answer.

3. Some of the buildings torn down during the 1950s and 1960s were as important to the history of Black Metropolis as the surviving ones that were nominated to the National Register. At the time, however, they were not seen as historic. By the 1980s the community perceived buildings like these, dating from the 1910s and 1920s, as important documents of history that needed to be preserved. What factors may have contributed to this change in perception? Why might the same types of buildings have been considered historic in 1985, but not historic in the 1960s?

Determining the Facts

Excerpt from the National Register Nomination for Chicago's Black Metropolis

The Black Metropolis Thematic nomination is comprised of eight individual buildings and one public monument which collectively represent what are among the most significant landmarks of black urban history in the United States. Centered in the vicinity of State and Thirty-fifth streets on Chicago's Near South Side, these properties are the tangible remains of what was once a thriving "city-within-a-city" created in the early part of this century by the city's black community as an alternative to the restrictions, exploitations, and indifference that characterized the prevalent attitudes of the city at large. In contrast to usual urban development patterns of the time where blacks settled in existing neighborhoods and buildings, the community at State and 35th streets was literally built from the ground up with its own economic, social, and political establishment, directly supported by black enterprise and capital. Contemporarily referred to by residents as "the metropolis," the development had firmly established itself by the turn of the century, and prospered until the 1930s when the Depression and socio-economic conditions virtually halted its further development.

The origin of Chicago's black heritage is synonymous with the origin of the city itself, one of the earliest recorded permanent settlers being Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, a French-speaking black who was engaged in trade with the Indians by the 1780s. Upon Point DuSable's departure in 1800, there was no significant black settlement in the area until the 1840s as Chicago was developing as a rapidly growing Midwestern city. At that time, blacks fleeing oppression in the South began to settle in Chicago, forming the nucleus for what was to develop into the first cohesive black community, which, according to census records, was comprised of 323 persons in 1850 and nearly tripled to 955 persons by 1860. The black community was not assimilated into the city at large, but was concentrated into small pockets throughout the city, the largest settlement being on the Near South Side, adjacent to the western fringes of the central business district. By 1870, the city's black population had grown to 3,691 persons, and steadily doubled in number with each succeeding decade. The boundaries of the South Side black community expanded southward in a long narrow strip, often known as the "Black Belt", bordered by the railroad yards and industrial properties to the west, the affluent residential neighborhoods adjacent to Wabash Avenue to the east, and extending south from Van Buren Street to Thirty-ninth Street, a distance of nearly five miles. The established white business and social communities of Chicago were largely indifferent to the black community, consequently it gradually evolved a complete commercial, social, and political base of its own. As the black community grew, the demand for goods and services was increasingly supplied from within the community itself, and had diversified to such an extent by 1885 that a complete directory of black businesses was published, The Colored Men's Professional and Business Directory of Chicago. Similarly, black-supported churches and social organizations proliferated, and evidence of the community's political strength was shown in the election of John Jones, to the Cook County Board of Commissioners in 1874. Jones, a downtown tailor of mixed free-black and white parentage, was supported in his election by both blacks and whites, and was the first black to hold elected office in the State of Illinois.

By 1900, with a population of 30,050 persons, the South Side black community began to take on the characteristics of a small "city-within-a-city," which paralleled the growth and expansion of the City of Chicago at large. A major factor in the growth of "black metropolis" after the turn of the century was its increasing access to financial resources due to the prosperity of the black community. The unwillingness of the established white financial community to support its enterprises ceased to be an impediment to growth. Through the great amount of money generated within the black community, an increasingly independent economic base developed, culminating in the establishment of Chicago's first black-owned bank founded by entrepreneur Jesse Binga in 1908. With greater access to financial resources, the commercial and business interests of Metropolis greatly diversified, with a wide range of professional, commercial, and manufacturing interests.

Growth was further intensified by an increase in the black population by 148% between 1910 and 1920, a period often referred to as the "Great Migration" due to the great numbers of blacks who left the South for greater opportunities in Chicago during that time. Despite the fact that it was in large part cut off from the economic and social mainstream of the rest of the city, Black Metropolis, with a population of 109,548 by 1920, had firmly established itself as a virtual self-contained metropolitan development.

Beginning with the establishment of the black-owned Binga Bank at 3633 South State Street in 1908, the vicinity of State and 35th streets was rapidly transformed into the Wall Street of the black community, housing a wide variety of commercial enterprises. Until the time of the Great Migration, the black business community was largely housed in existing residential and small storefront buildings which were adapted for business purposes, often with unsatisfactory results. New construction was limited mainly to a handful of small one- and two-story structures which were erected as investments by white speculators with an eye on the growing potential of the black economic market. This trend was reversed in 1916 when ground was broken for the Jordan Building, at the northeast comer of State and 36th streets, an impressive three-story combination store and apartment building which was commissioned by songwriter and music publisher Joseph J. Jordan. The precedent of the Jordan Building was closely followed by a series of ambitious black-owned and -financed building projects which were carried out along South State Street throughout the 1920s. The most important of these included the Overton Hygenic Building, a combination store, office, and manufacturing building commissioned by the diverse entrepreneur Anthony Overton in 1922; the Chicago Bee Building, also commissioned by Overton in 1929 to house the Chicago Bee newspaper; the seven-story Knights of Pythias building erected in 1926 by a prominent lodge order after plans by Chicago's first black architect, Walter T. Bailey; and the quarters of the Binga State Bank and the Binga Arcade Building, erected by Banker Jesse Binga in 1924 and 1929 respectively. Of these buildings, the Jordan, Overton Hygienic, and Chicago Bee buildings still survive, largely as originally designed during the boom time of Black Metropolis.

In marked contrast to the staid banks, insurance companies, and professional offices which conducted business by day on State Street, the area was magically transformed by night by the bright lights and exciting sounds of the numerous nightclubs and all-night restaurants which were interspersed throughout the business district. These were the popular jazz clubs where such notables as King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, and Jelly Roll Morton played and earned Chicago its reputation as a jazz center in the 1920s. Many of the musicians had arrived from New Orleans, St. Louis, and other points south, each bringing with them characteristics of the musical style of their origins, yet the combination of regional styles soon melded into a distinct musical character which was uniquely Chicago. Beginning with Robert T. Motts' Pekin Theater at 2700 South State Street, which opened in 1905, Black Metropolis began to develop numerous music-oriented clubs and cafes during the following decade, reaching their height in the 1920s. Among the most famous were the Dreamland Cafe at 3618 South State Street, the Royal Gardens (later Lincoln Gardens) at 459 East 31st Street, and the Elite Club at 3030 South State Street. A notable and notorious club was the white-owned Panama at the southeast comer of State and 35th streets, where actress and cabaret performer Florence Mills got her start as part of the Panama Trio, and whose pianist was the noted performer and songwriter Tony Jackson, who is best known for composing the million-dollar hit "Pretty Baby" in 1916. The musical intensity of the area was such that it once was suggested that if a horn were held up at the comer of State and 35th streets, it would play itself because of all the musical winds circulating in the area.

Churches played an important role in the development of Black Metropolis, both from a spiritual as well as a social standpoint in the community. Large congregations such as the Olivet Baptist Church and Pilgrim Baptist Church conducted extensive social programs, and were instrumental in securing lodging and employment for the newcomers which arrived from the South during the "Great Migration." Similar programs were conducted at the Wabash Avenue Y.M.C.A. which opened in 1914 through the impetus of philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, the President of Sears, Roebuck & Company, who had considerable interest in black-oriented causes. Programs at the Y.M.C.A. included extensive job training programs including such specialized programs as auto repair and manual training.

Organized political alliances gave Black Metropolis increased participation in city government, beginning with the election of Oscar DePriest as the city's first black alderman in 1915. Initially working in alliance with the white Republican bosses who controlled the political destiny of the Black Metropolis wards, DePriest sought to build a political organization of his own, forming the "Peoples Movement Club," with headquarters in a former Jewish social club at 3140 South Indiana Avenue. While DePriest's organization was the most influential of the black political organizations, it faced stiff competition from other organizations and rival political figures within the black community. The political voting strength of the Black Metropolis wards was such that by the 1920s the political control was effectively taken from the white political bosses who formerly controlled them, and put into the hands of political figures from within the black community. Gains were made in representation in municipal government as well as in the state legislature, and in 1928 Oscar DePriest had the distinction of being the first black from the North to be elected to a seat in the United States House of Representatives, serving for three consecutive terms.

The Black Metropolis development gained nationwide publicity as a model of black achievement, with extensive coverage in both the white as well as the black press of the time. Chicago was one of the centers of black journalism, having at different times several black-owned newspapers, including the Chicago Whip, Chicago Bee, Broad Axe, and the Half Century Magazine. The most influential of the Chicago publications was the Chicago Defender, a newspaper of nationwide circulation which was founded by Robert S. Abbott in 1905. The Chicago Defender had a major impact on black thought and development in America by its combination of news items pertinent to blacks nationwide in conjunction with strong editorial viewpoints on a wide variety of civil rights issues. The "Great Migration" of 1910 to 1920 was due in large part to editorials published in the Chicago Defender urging blacks to leave the oppression of the South for greater opportunity in Chicago and the North.

Black Metropolis reached the height by the mid-1920s, but its economic vitality began to gradually weaken after 1925 due to socio-economic conditions which were out of the control of its developers. Although the growth and prosperity of Black Metropolis was directly tied to the rapid growth of the black population, particularly during the Great Migration, the sharp decline in new arrivals during the 1920s slowed its development. As employment opportunities did not keep pace with the population increases of the previous decade, unemployment weakened the financial base of the community, adversely affecting the businesses of Black Metropolis which were reliant on support from within the black community. Further deterioration of the financial base occurred when white businessmen who previously had ignored the black community began to realize its economic potential. Rather than attempt to break into the prosperous existing market at 35th and State, an alternate business area was created along 47th Street principally developed and financed by white developers and store owners who controlled the property to such an extent that black-owned and -developed properties and businesses were largely excluded from the area. The introduction of established white chain stores and commercial enterprises along 47th Street gave insurmountable competition to the independent black business of the 35th Street district and progressively siphoned off its energy and self-supporting financial base. The final blow to Black Metropolis came with the Great Depression of 1929 which closed down most of its black-owned banks, insurance companies, and other business interests, while many of the businesses of 47th Street with their broader access to credit and nationwide financial backing remained largely intact. The self-supporting momentum of Black Metropolis, which its backers had hoped would lead to recognition and eventual integration with the established downtown business establishment, was thus dealt a serious blow from which many negative after-effects lingered for decades.

After the 35th Street district lost its principal business interests during the Depression, the area quickly declined, and by 1950 one local writer dismissed the intersection of 35th and State streets as "Bronzeville's skid-row." Deterioration and urban renewal took their toll during the 1950s and 1960s resulting in the demolition of entire blocks along State Street for the construction of public housing projects and the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology, as well as extensive isolated demolitions throughout the community.

Fortunately, many of the most significant buildings of the Black Metropolis development have survived, although some are in a state of neglect and deterioration. Collectively, these buildings are worthy of recognition and preservation as monuments to the determination of the black urban pioneers who created them.

The reading was excerpted from Timothy Samuelson, "Black Metropolis Thematic Nomination" (Cook County, Illinois) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1986.

Visual Evidence

Drawing 1: The Engine of Progress

(The Negro in Chicago, 1779-1929, Washington Intercollegiate Club of Chicago, Inc., 1929.)

This image appeared in The Negro in Chicago, 1779 to 1929, a 312-page compendium subtitled "the Wonder Book," which celebrated the accomplishments made at a high point of the community's development. "The Engine of Progress" accompanied a short article which lamented the fact that most African Americans had their savings invested in institutions that "generally exploit Negroes and certainly won't employ them above the level of janitor." But the Black Metropolis, with its own institutions, held hope that there was "a great future in store for the Negro in Chicago."

1) What is the central image in this drawing?

2) The buildings pictured are, clockwise from upper right, the Chicago Defender Building, the Knights of Pythias building, the Chicago Bee Building, the YWCA building, and the YMCA building. Why do you think the artist chose to include each of these buildings? (Refer to paragraphs 5, 7, and 9 of the reading.)

3) What does the artist view as the "engine of progress" for African Americans in 1929? How might it "pull" them to a better future ?

Visual Evidence

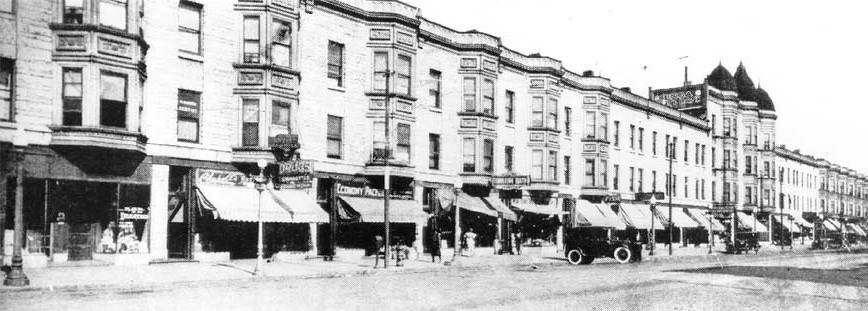

Photo 1: State Street, 1925.

This image was well known in the African American community. First published in 1925, it was reprinted four years later in The Negro in Chicago. This area of State Street (just off the top of Map 3) was located in an older section of black businesses closer to the downtown area than Thirty-fifth Street.

1) Which of the following black-owned businesses that occupied this stretch of buildings would you expect to find in a neighborhood shopping center today: a drugstore, a barber shop, a florist, a tailor, a music store, a photographer, a millinery shop, and a fish market? How might shopping here in the 1920s differ from your shopping experiences today?

2) List the most obvious differences between the buildings pictured here and those found in Drawing 1. What might account for these differences?

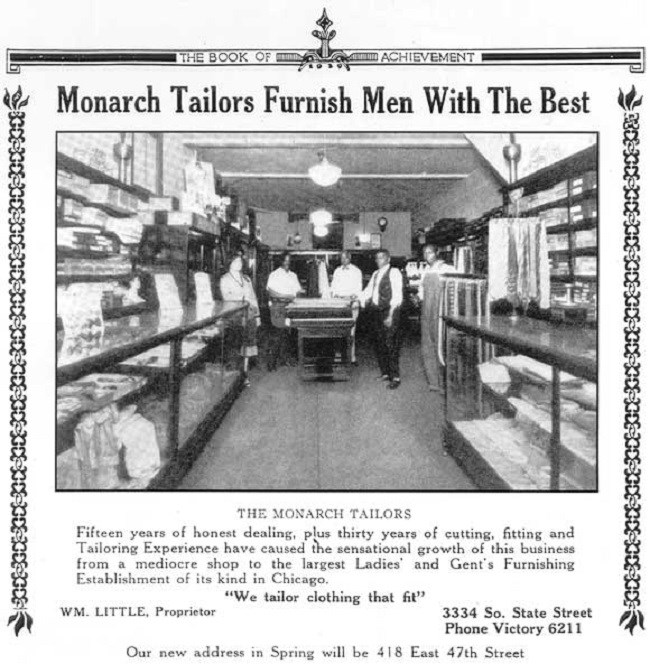

Visual Evidence

Photo 2: Monarch Tailors advertisement, 1929.

(The Negro in Chicago, 1779-1929, Washington Intercollegiate Club of Chicago, Inc., 1929.)

In 1956 the building that had housed Monarch Tailors when this photo was taken was destroyed by the Illinois Institute of Technology to make way for Crown Hall, a well-known building designed by a famous modern architect.

1) Does this advertisement relate to the "engine of progress" theme of Drawing 1? If so, how?

2) What additional information can be gained by reading the text that accompanies the photo in this advertisement? Do you think this would have been an effective ad at the time? Why or why not?

3) Note the announcement at the bottom indicating that Monarch Tailors would soon move from State Street to Forty-seventh Street. What are some possible reasons for the move?

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: Overton Hygenic Building, 1927.

(The Negro in Chicago, 1779-1929, Washington Intercollegiate Club of Chicago, Inc., 1929.)

Anthony Overton's firm, which manufactured and sold cosmetics to African Americans, was well known across the nation. In 1922-1923 Overton erected the Hygenic Building at 3619-27 S. State Street as a "monument to Negro thrift and industry." Born of former slaves in Louisiana in 1865, Overton graduated from the University of Kansas in 1888. He ran a general store in Oklahoma and eventually established a cosmetics company in Kansas City. In 1911 he moved the firm to Chicago where his success expanded to other businesses, including a bank and an insurance company.

Each floor of this building was used for a different purpose. The cosmetics manufacturing took place on the top floor while other aspects of the business, including sales, accounting, and advertising, occupied the third floor. The second floor held the Victory Life Insurance Company as well as rental space for professional offices. The first floor housed a drug-store, the Douglass National Bank, and other commercial ventures. In 1929 Overton claimed that the Douglass Bank was the largest bank "in the United States owned and operated by colored people." It had about 64,000 depositors residing in 30 states.

1) Why did this building house so many different businesses?

2) Why would out-of-town people have used Douglass Bank? How do you think they would have known about this Chicago bank? (Keep in mind that white-owned banks often would not make loans to black businesses.)

Visual Evidence

Drawing 2: The Chicago Bee Building.

(The Negro in Chicago, 1779-1929, Washington Intercollegiate Club of Chicago, Inc., 1929.)

This drawing was part of an advertisement for the Chicago Bee. Anthony Overton founded the newspaper for "civic and racial improvement and development" and to promote black business. Aiming for national circulation, Overton wanted a distinctive building in the latest architectural style to house the Bee. Erecting such an elaborate structure at 3647-3655 S. State Street between 1929 and 1931 was also a show of confidence in the old center of Black Metropolis.

1) How is this building different from the Overton Hygienic Building?

2) How would designing the building in the popular Art Deco style support the purposes and philosophy of Overton and his newspaper?

3) How are the Chicago Bee and its new building connected to the engine of progress theme?

Putting It All Together

"Touring" Chicago's Black Metropolis in the late 1920s with the aid of these sources puts students in a position to advance some general conclusions about the stories of this community. Using some reflective thought, they also can spell out the factors that turn seemingly ordinary places into special historic places. Students can then begin to assess buildings in their own communities from a historical perspective.

Activity 1: The Time Perspective

A variety of dates, periods, and major events appear in the lesson. One way to put them together into a meaningful sequence is to use a time line. Have students construct a time line with a scale of dates down the center of the page. Ask them to select 10 significant events from the information in this lesson and write them to the left of the dates. Ask students to use the right-hand side of the time line to label historical periods, using their American history textbooks for reference. (For example, a student might use the following periods: Reconstruction, 1865-1877; Industrial Growth/Gilded Age, 1873-1900, Imperial America, 1890-1904; Progressive Era, 1900-1920; World War I, 1914-1919; etc.)

After students have completed their time lines, have them share their periodization schemes (time periods organized by themes) with each other. How similar or different are they from each other? How well do students think the story of Chicago's Black Metropolis fits into the themes that define these periods? Where do they overlap? How do they differ? Point out to students that a variety of periodization schemes and terms for identifying themes can be used to define the same series of events. These might be determined by someone's life story, a community's development, national events, or world affairs. With this in mind, ask students to create a periodization scheme specifically for the historical evolution of the Black Metropolis.

Activity 2: Creating a Historic Place

For a location to be considered historic it must be invested with meaning by connecting it to the larger story we call history. Have the class discuss the process by which we "transform" structures into historic places. The time lines created in Activity 1 might give substance to this discussion by furnishing concrete examples. Map 3 and paragraphs 10-12 of the reading provide useful information as well. Encourage the students to use the information generated by the discussion to draw a flowchart that shows the process by which people invest places with historical meaning.

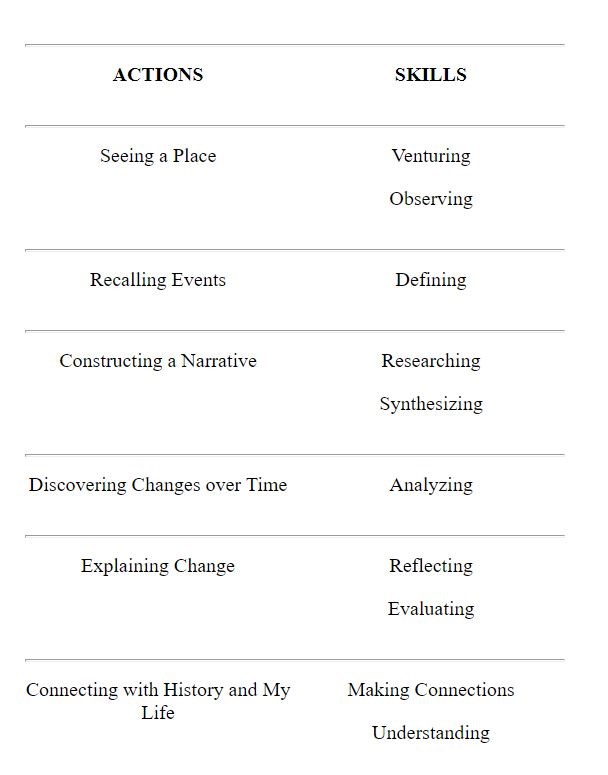

One of many ways to describe this process is indicated on the chart below. Have the class compare their flowchart with this one, perhaps incorporating an idea or two. Remember that the resulting flowchart is probably not nearly as valuable as the thought process that was used to create it. Considering several different charts will enrich the conversation.

Activity 3: Nominating a Local Historic Place

The process outlined on the chart is the same used to identify and evaluate historic places in students' own communities. Ask each student to select a site, building, monument, or structure in their community that could be nominated for a local, state, or national register of historic places. Have them complete the "action" steps in the chart for that place and use the information to create a narrative similar to the reading. This information will be similar to the documentation needed for an actual nomination.

Next discuss where appropriate maps might be located to place the site into a geographical as well as a historical context. Maps similar to United States Geological Survey quadrangles used for Map 2 are available for almost every place in the nation and for a variety of dates from the late 19th century to the present. A librarian can help students locate them. Extend the discussion to explore where other appropriate source documents for one particular site might be located.

This activity could be extended to a large, cooperative project for a nomination to have the place listed in a local, state, or national register, or for a history fair, term paper, classroom display, or videotape. If so, explain the importance of consulting a history textbook or other reference materials to establish the pertinent historical themes, of organizing the story chronologically by using a time line, and of visiting the location in person, keeping notes of one's observations, ideas, and feelings.

Chicago's Black Metropolis--Supplementary Resources

Chicago's Black Metropolis: Understanding History Through a Historic Place considers how one of the most remarkable internal population movements in U.S. history affected one city. Below are materials for further exploration of both Black Metropolis and the Great Migration.

Black Metropolis

At Home with Art & Industry: 1890-1920

The Illinois State Museum created this lesson, which focuses on Ruby Livingston, who migrated to Chicago from Mississippi in 1914. It also includes other information on why people moved north, often in their own words.

Chicago Historical Society

Visit the Chicago Historical Society's website for more information about the city.

The Great Migration

Library of Congress

The American Memory collection offers a wide variety of resources about the Great Migration. Start with the search engine, being sure to choose "Match this exact phrase" before you enter the phrase you want to search.

Tags

- black history

- african american history

- chicago

- african american history and culture

- african american sites

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- illinois

- illinois history

- migration and immigration

- gilded age

- early 20th century

- progressive era

- midwest

- labor history

- twhplp

- etc aah