Part of a series of articles titled Suffrage in America: The 15th and 19th Amendments.

Article

Voting Rights: Celebrations of Success

How does it feel to achieve your dream?

Carrie Chapman Catt albums, Special Collections Department, Bryn Mawr College Library

The ratifications of the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, fifty years apart, were exciting times for many people. On March 30, 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant officially confirmed the 15th Amendment as part of the Constitution. An article ran in the National Republican on the following day, calling the amendment “...the crowning act in the total and entire emancipation of the colored race.” The article went on to declare that, “the message of yesterday is an outburst of a noble, manly nature rejoicing that the status of the colored man is permanently and satisfactorily fixed…” While this statement exaggerates the impact of the amendment, it conveys people’s feelings of excitement and hope for a more just and democratic society.

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93510386/

Throughout the long struggle for voting rights, people devoted time, energy, and resources to making society better for everyone. The ratification of the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments marked historic moments in time. While the amendments had significant limitations and did not result in universal suffrage (the right to vote), they still made a difference. For the first time, the law of the land recognized that discrimination based on race and sex is illegal. The amendments represented the culmination of decades of hard work, sacrifice, and dedication on the part of men and women across the United States. In the aftermath of the amendments’ ratification, people celebrated the outcome of their efforts. Those who benefited from the amendments celebrated their ability to participate in the political process and affirm their status as citizens of the United States.

These celebrations were often large and public. To celebrate the Fifteenth Amendment, African Americans gathered at places in their local communities such as the Thaddeus Stevens School in Washington, D.C. and the Washington Monument in Baltimore. On May 19, 1870, more than 10,000 Black individuals paraded through Baltimore while over 20,000 spectators looked on. Twenty carriages carried honored guests while many groups marched alongside them, including policemen, firemen, schoolchildren, and military bands. When the parade reached Monument Square in downtown Baltimore, the participants heard readings and speeches by abolitionists Charles Sumner, William Lloyd Garrison, and Frederick Douglass.

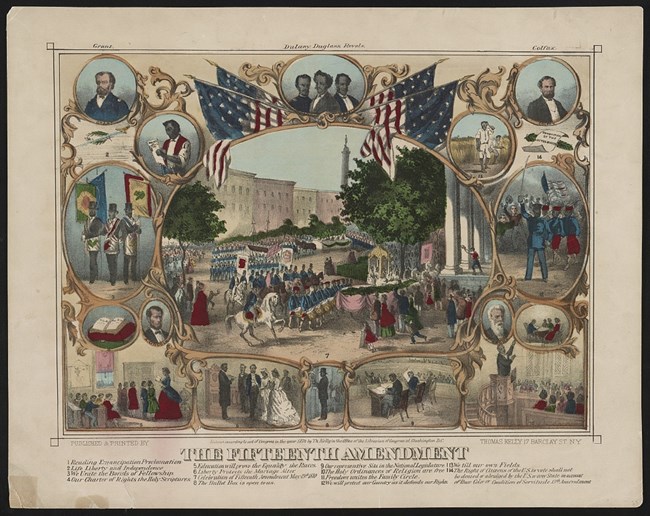

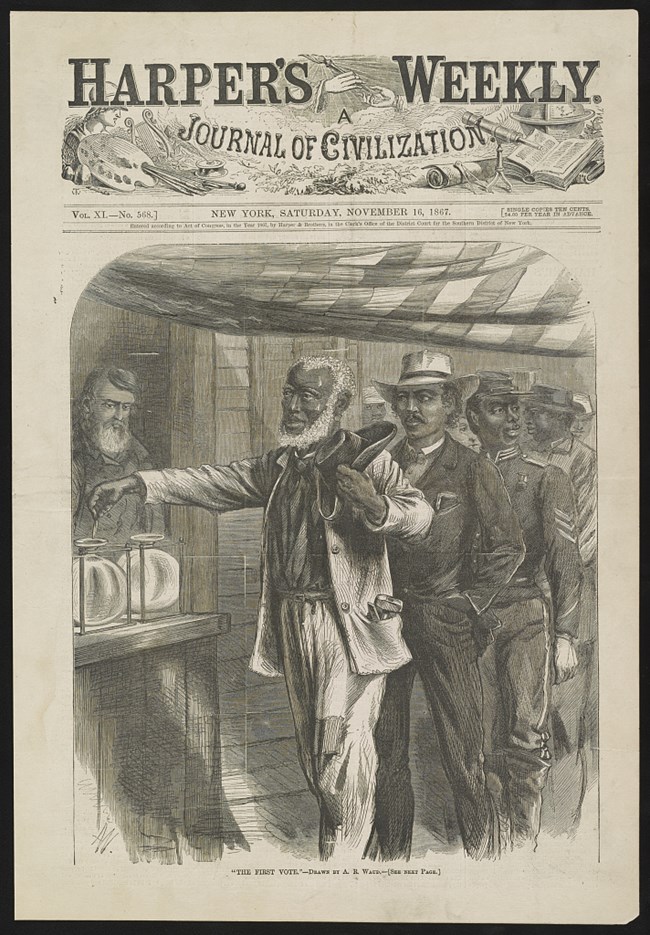

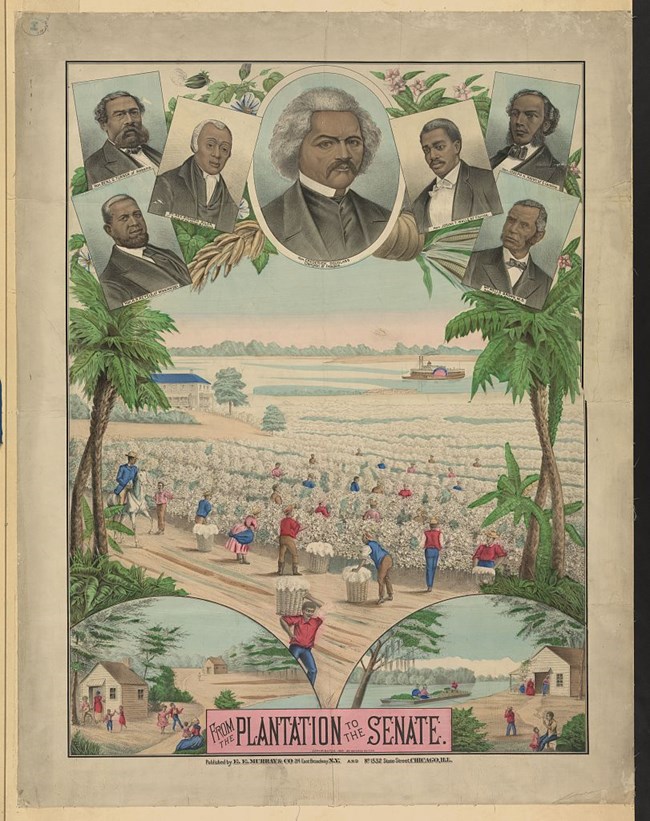

Artists created large prints to commemorate the Fifteenth Amendment. Several of these illustrations showed celebrations, including the parade in Baltimore. The posters also featured abolitionists, politicians, activists, and other leaders, such as John Brown, Ulysses S. Grant, Frederick Douglass, and Abraham Lincoln. Many of these prints had various scenes of African Americans engaged in everyday activities, such as farming, attending church, voting, and attending school. Artists used these works to tell the story of how African American men came to have the right to vote, and how the Fifteenth Amendment would help them participate more fully in American society.

Women also celebrated the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 with ceremonies and parades. At Independence Square in Philadelphia, suffragists celebrated their victory by ringing the Justice Bell, a replica of the Liberty Bell. The bell rang 48 times, to represent each state in the union. The Justice Bell is now located in the Washington Memorial Chapel at Valley Forge National Historical Park.

Library of Congress, Harris & Ewing Collection. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016885217/

Library of Congress, Harris & Ewing Collection.

https://www.loc.gov/item/2016885217/

The suffragist Alice Paul made an enormous flag to commemorate the Nineteenth Amendment. Every time a state ratified the amendment, she sewed a ratification star onto the flag. Thirty-six votes were needed to pass the amendment. When the 36th state (Tennessee) ratified the amendment, Paul put the last star on the flag and hung it outside the National Women’s Party headquarters.

Elections were another opportunity to celebrate the right to participate in the political process. Women and Black men voted in local, state, and national elections as soon as they could.

They also ran for and held political office in order to make further changes to create the kind of society they wanted to live in. More than 1,400 African American men held offices during Reconstruction. At the local level, African Americans served as policemen, sheriffs, judges, and mayors. They held positions as state representatives, state treasurers, and secretaries of state. Sixteen African American men were elected to Congress during Reconstruction. Remarkably, nine of them had been born into slavery, and were now serving in federal offices.

Women had held political offices before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, but did so in greater numbers and held higher-status positions after 1920. The 65th Congress (1917-1919) had only one female member, but by 1929, there were nine female members. The decade following the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment saw many firsts for women: in 1923, Soledad Chacon became the Secretary of State in New Mexico, the first Latina and first woman of color to hold a statewide elected executive office; in 1924, Cora Belle Reynolds Anderson of Michigan became the first Native American woman in a state legislature; and in 1925, Wyoming saw Nellie Tayloe Ross become the nation's first woman governor.

Last updated: October 9, 2020